1 Characterizing the acoustics of places of worship

Should we believe in acoustic indicators?

Introduction

A worship space can be defined as any space where worship activities can be held. This means that significant variations in capacity and size are to be expected (e.g. from a small chapel to a large cathedral). In addition, each worship group may have its own specificities with regards to its worship space. More to the point, different trends can often be found in the spatial planning of the space according to historical period and sometimes even to location. Last but not least, there has been an evolution in the style and even the purpose of worship spaces – an evolution often reflected in their architectural features, including acoustics (Kilde 2002).

Incidentally, a worship space is not inevitably a regular building. There are well-documented instances of boats being used (e.g. “temple-péniches”, Protestant church barges on the Seine in the early 20th century (Musée virtuel du Protestantisme 2019), and other missionary boats). There were even worship spaces in railway vehicles: there are still examples of church trains in Africa, and church coaches were also used along the Trans-Siberian Railway and in America (Taylor 2010; Railroad chapel car 2019), where they were being built up until the 1950s. Sometimes, a worship space may be out of doors, though it must often be quite difficult for the officiant to make himself understood without electro-acoustic help (Galbreath 2014).

As a general rule, worship spaces are meant to foster cohesion between members of the community and help transmit the message delivered by either the priest or the whole group of members. While such a message is usually vocal, it can also draw on musical instruments, or deploy a mixture of both. Large worship spaces are usually meant to impress, which is often achieved through large – if not monumental – proportions. Acoustics can serve many purposes, for example amplifying the music and songs as well as the voice of the officiant while preventing unwanted noise from intruding. An art historian noted that “Reciters turned mosques into stages for the melodic rendition of the Qur’an or, one might say, sound boxes resonating the Holy Text” (Ergin 2008).

It is not unusual for worship spaces to advertise their function with a few architectural symbols (a bell tower, a minaret, a cross, a crescent, a triangle, etc.). But this is not always the case: when freedom of worship was denied, some citizens could actually use so-called prayer houses that were indistinguishable from ordinary buildings on the outside (e.g. a barn or even a small house) (Musée Virtuel du Protestantisme Français 2019).

The larger the volume and the fewer the fittings, the longer the reverberation time (roughly speaking, the reverberation time is the time taken for a stable sound to fade completely from the moment it is cut off). While this is good for music and singing purposes, intelligibility will usually suffer. Depending on the historical period and the worship group, and even the geographical location, the requirements for intelligibility may vary, with direct consequences for the preferred reverberation time value and the volume, fittings, and finishes. Such options are also reflected in the sacred music or songs to be performed in these worship spaces, or in the decision to focus on speech. But is a mere reverberation time sufficient to describe the acoustics of a worship space? As such physical parameters as reverberation time and background noise level do not account for everything, attention also needs to be paid to psycho-acoustic attributes, and a degree of historical understanding may be needed too.

The aim of this chapter is to set out for those interested, and especially for non-acousticians, the acoustic challenges faced by the acoustic consultant. In order to understand these challenges, a brief reminder of a few parameters in physical acoustics will be given. This will be followed by an equally brief reminder of several significant psycho-acoustic attributes. Next, a few points of interest will be examined (e.g. a number of typical standards and requirements applicable to worship spaces), and these will be illustrated by examples. We will then examine a few trends in the construction and renovation of worship spaces with regard to their acoustics and make some concluding remarks about their impact on acoustic engineering.

Describing the acoustics of a space

What is being sought?

The worship space is there to welcome – and protect – its users. As such, it needs to protect them from the outside environment, including noise. It also needs to reduce the amount of noise emitted to the outside environment by activities inside the facility. This means that the design team must really pay attention to sound insulation. Then the design team must also make sure that the interior acoustic climate is well suited to the worship activities. This means that the design team must also pay close attention to room acoustics. Last, the design team (i.e. the architect and his or her engineers) must control the noise emitted by building equipment (e.g. heaters, coolers) and also make sure that specific pieces of equipment that may be required for worship activities (e.g. organ, bells, loudspeakers) comply with the community noise control regulations in force. While these are often set out at national level, there may be specific local regulations that will introduce additional constraints (e.g. a township may decide against the use of acoustic signals either during specific time periods or even permanently).

Relationship to the outside environment

While some worship spaces attempt to disappear into their surroundings (e.g. various Protestant churches, sometimes because of a historic need to avoid immediate danger (Asselineau 2015)), quite often there are some very distinctive signs that will announce the purpose of the worship space (e.g. such visual signs as a minaret, a bell tower, and so on).

However, these signs often include acoustic signals: the call to prayer by muezzins is quite a familiar case, and some people may not be happy with it. But one should not underestimate the noise from church bells, either, and controversies frequently arise from the close proximity between worship spaces and non-believers (Dessureault 2015; Tanoh 2010). More to the point, the noise from the assembly of worshippers, especially when singing, can be quite significant, to the extent that there are regulations and recommended practices covering this aspect (Loi n° 98–030 1999 Flores-Lonjou and Messner 2007; Arrêté Préfectoral n° 2008, 193–7). The noise from musical instruments, especially the organ, which often emits sounds well down in the low frequency range, can be quite significant too.

Whenever the worship space is part of a larger set of buildings which may include residential spaces, or when there is a quiet neighbourhood around, special precautions must be taken regarding the noise control of the premises with regard to their environment.

One also has to consider potential noise coming from the outside into the worship space. This is especially true of churches where large stained-glass windows can often be found. Should a road with heavy traffic flow be nearby, this can lead to a problematic background noise level inside the premises (Peutz and Associates 1997).

Internal acoustics

Everyone has used such descriptive words as “dead” or “live” when talking about the acoustics of a room. These terms are well known to musicians and even architects when talking about an absorptive or reverberant space, respectively. But if we look into the issue more closely, we sometimes find that other attributes are also taken into consideration by psycho-acoustically oriented people too: quiet/noisy, dull/bright, and so forth.

While such words provide a hint about the perceived acoustics of the space, they are not usually that much use to the acoustician (especially if specifications are provided in a later contract!). That is why acoustic researchers from the mid-20th century to the present have sought to propose a limited set of acoustic indicators which can characterize the descriptive qualities of a room. I will outline a few common physical parameters that are often considered.

Actually, the acoustician prefers to use various easy indicators to measure parameters such as reverberation time in order to help commission the facility. More to the point, it is also easy to explain the consequences of their choices by comparing their project with similar existing facilities. On the other hand, most clients are not at all familiar with acoustic terms and definitions, and it will be one of the tasks of the acoustician to give them some basic instruction in order for them to better understand those consequences and integrate them into their project.

One important aspect concerns sideline activities: nowadays a facility, be it a worship space or something else, often pays for itself by being rented out for other purposes, and this applies to some worship spaces too, as long as these extra activities are not in contradiction with the dictates of worship. Sometimes adjustable elements (e.g. either curtains or reflective panels) have to be prescribed in order to allow for multi-use of the space.

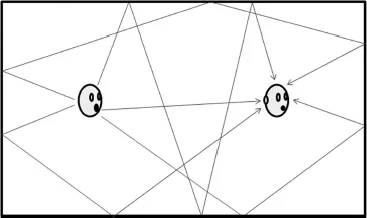

Reverberation time

Reverberation is the product of the multiple acoustic reflections from the inner surfaces of a room (Figure 1.1). In a well-balanced room, these reflections will be well spread over the observation time span, with the listener unable to point out a specific reflection. But if several reflections reach the listener’s ears at the same time, without much acoustic energy around, then one has an echo. To be discernible this event must be at least 100 ms from any other event (this has a practical consequence: a reflective rear wall will not be positioned any further than 17 m away from the speaker).

Figure 1.1 Example of acoustic reflections in a room resulting in reverberation

The reverberation time, given by the symbol T or RT, is defined as the time needed for the sound pressure level to drop by 60 dB from the moment the sound source is cut off. Its measurement calls for a sound source that can be cut off abruptly. The choice of measurement points is described in standards, for example ISO 3382–1 for ordinary rooms (ISO 3382–1 2009) and ISO 3382–2 for performance halls and similar large venues (ISO 3382–2 2008). A physicist by the name of Sabine who taught at Harvard University had been puzzled by the different acoustic qualities of rooms of apparently similar volume. He realized that the acoustics of his theatre depended on the number of attendees and cushions in it. Eventually he described the room’s acoustics through the duration of a sound emitted in a room and cut off so as to fade away completely.

Carrying out experiments at night time (definitely the way to work in acoustics!), and using the cushions from other rooms, he eventually discovered the proportionality of the reverberation time to the volume of the room, as well as the notion of absorption quantity (through the number of imported cushions). Sabine’s formula reads as:

where:

- V is the volume of the venue

- A its absorptive area, which essentially depends on the materials on the walls

- K is a coefficient with the value 0.163 in the metric system (Asselineau 2015).

In order to better cover the aspects linked to articulation (both for speech and music), Early Decay Time, given by EDT, was introduced. EDT is defined as the time needed for the sound pressure level to drop by 10 dB f...