This is a test

- 140 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

René Magritte and the Art of Thinking

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

For René Magritte, painting was a form of thinking. Through paintings of ordinary objects rendered with illusionism, Magritte probed the limits of our perception—what we see and cannot see, the nature of representation—as a philosophical system for presenting ideas, and explored perspective as a method of visual argumentation. This book makes the claim that Magritte's painting is about vision and the act of viewing, of perception itself, and the process of how we see and experience things in the world, including paintings as things.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access René Magritte and the Art of Thinking by Lisa Lipinski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Modern Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Bringing Thought to Life

In 1919, René Magritte embarked on the adventure of modernism, a second age of modernity—as distinct from the early modern period of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—in an industrialized European world that had just emerged from a devastating world war. New forms of art-making challenged the traditional systems of art exhibition, representation, and practice: cubism and collage, photography and new techniques of mechanical reproduction, and the iconoclastic gestures of the Dada artists, most notably Marcel Duchamp’s readymades. Magritte was intrigued, and, as he told an interviewer in 1962, in the early 1920s he experimented widely: “I was looking. My painting was a continual research. I was strongly influenced by cubism, futurism, abstract art, all styles of the avant-garde.”1 Later in the interview, he explained the reason for his attachment to painting as his research vehicle: “For me, painting is bringing my thoughts to life. I very much like poets and writers, but I am not a writer, so I think in images, not in novels or in poems.”2 What could be said of Magritte from a contemporary point of view is that he was a conceptual artist avant la lettre, working within the confines of a storied medium without much interest in matters of style and self-expression.

In the standard narrative of Magritte, he was a painter who first dabbled in abstraction, producing derivative and unoriginal paintings in a cubist and then futurist idiom until he discovered the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio de Chirico in the mid-1920s, which set him on the road to surrealism. Until recently, Magritte’s early “pre-surrealist” paintings therefore have not figured prominently in the Magritte scholarship. Now, however, as they are being looked at more closely, they can be seen as a logical prelude to his mature work. Roger Rothman, for example, argues that Magritte was interested not in the techniques but in “the ontological implications of Modernist painting—and the discourses around it. Magritte exploited the confusion between painting-as-picture and painting-as-thing—a confusion that the bulk of mainstream Modernist painters recognized, yet sought to avoid.”3 Invoking Maurice Denis’s famous dictum, “Remember that a painting, before it is a battle horse, a nude model, or some anecdote—is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order,”4 Rothman notes that “Magritte operated under the paradoxical premise that a picture, while also being a war horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered by colors in a certain order.”5 Rothman refers to this dualism as a paradox, which he claims Magritte put to use in selected works by rendering abstraction as an object in itself, a thing like any other thing. He observes that Magritte did not fully relinquish abstraction, at least not in his early surrealist works from the 1920s, and that even in his word paintings, abstract forms make an appearance.

Like Denis, modernist art theorists and art historians have defined modernist painting as characterized by flatness and abstraction, ultimately banishing the figurative to the margins. For Magritte, however, the relationship between the superficially competing ideas of painting-as-object and painting-as-picture was an infinitely interesting terrain. Throughout his career he continually interrogated painting by way of its formal means, whether representation by resemblance (illusionism) or non-resemblance (abstraction). Rothman and Silvano Levy maintain, and support with convincing evidence, that this period of experimentation with avant-garde painting was central to Magritte’s self-reflexive art practice as a surrealist. He brought its lessons to his later paintings.

After his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Brussels between 1916 and 1918, Magritte quickly aligned himself with the Belgian avant-garde, who were creating and debating self-reflexive ideas about the nature of art produced by the most revolutionary movements—not only cubism but also the abstraction of de Stijl and purism. In 1919, Magritte coauthored “L’Art pur. Défense de l’esthétique” (“Pure Art: In Defense of the Aesthetic”) with Victor Servranckx, a leading abstract painter in Belgium. The essay, which was not published during their lifetimes, demonstrates Magritte’s alignment with the avant-garde in Brussels and expresses a concern with the status of representation and modern painting. Regarding the cubists, Magritte and Servranckx write: “Wishing to respect the properties of the canvas, the flat two-dimensional surface, they have rediscovered the unchanging laws of painting.”6 But there is more to pure painting, they argue, than respecting the two-dimensionality of the picture plane. A picture is a constructed object, a thing in the world that follows its own structural laws, and, like any object, it should be well made. In the same paragraph, they caution that fixing one’s style before painting is a mistake. The creative idea must not be subordinate to the look of the picture. If the idea requires perspective, the artist must sacrifice flatness, “for the canvas has to perform its duty, not the painter, and he does not paint merely in order to cover a canvas with colors, just as the poet does not write merely to cover the page with words.”7 In other words, painting is a form of thinking and it exercises agency. Their essay is consistent with the ideals of art espoused by Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant, as well as with the late-cubist theories of Pierre Reverdy, but Servranckx and Magritte do not insist that painting be “pure” in the sense of maintaining its flatness or stylistic uniformity above considerations of the subject. In relation to the latter, Magritte freely mixed the cubism of Robert Delaunay with the stylization of Art Deco.

Early on, then, Magritte was searching for a language, a subject, and a way to treat that subject. Rothman’s reevaluation of the significance of Magritte’s pre-surrealist painting is important, but it does not challenge the standard art-historical approach, the opposition of formalism and iconology. In his account, in Magritte’s paintings abstraction becomes another icon, albeit an object lacking resemblance. However, Magritte’s focus was on larger issues of representation, including the infusion of feeling into analysis and pleasure into painting. In 1922–1923, he painted a unique series of post-cubist figurative works, mostly nudes, that combine geometric stylization with sensual and erotic overtones. The dialectic of the analytic and the erotic is often present in Magritte’s work, whatever the visual lexicon he uses; when he earlier experimented with futurism, he did not focus on the premises of the movement so much as on its applicability to his own preoccupations, later recalling: “I don’t think I was a very orthodox Futurist because the lyricism I wanted to master had an unvarying center, unconnected with artistic Futurism. It was a pure and powerful feeling: eroticism.”8 Femmes (Women), 1922, is a fine example of Magritte’s post-cubist work. Three slender pale standing nudes float in a nebulous space, surrounded by geometric shapes painted in deep, rich saturated blues, black, red, and orange. With their arms around each other, they pose for the beholder. Distinctive diagonal lines and flat shadows intersect the bodies and space, adding rhythm to the whole and directing our gaze to the erogenous zones. The sexiness of the semi-abstract figures derives from the accentuated curves of their bodies and pubic hair, their frank nudity, and the tenderness with which they interact, physically and emotionally, like the Three Graces.

The painting was exhibited at the Galerie Georges Giroux in Brussels in 1923. In a review, Pierre Bourgeois singled out Magritte, noting his nonconformity with modernist principles of pure form:

The case of René Magritte is a curious one. . . . Impregnated with modern art, he always gives the impression of being a ‘maverick’ among modernist experimenters. . . . We see him investigating the eternal female nude and expressing his feverish passion with an insistent love. To intensify the rhythmic significance of the bodies, triangles and colored patches constitute a simple and melodious background to them. A passionate and cerebral life thus affirms its provocative unease.9

From the beginning of his career, then, Magritte’s unsettling fusion of emotion and reason was acknowledged by discerning viewers such as Bourgeois, and the artist would continue to find new ways to arouse this particular disquiet after his move into surrealism.

A Poetic Revelation

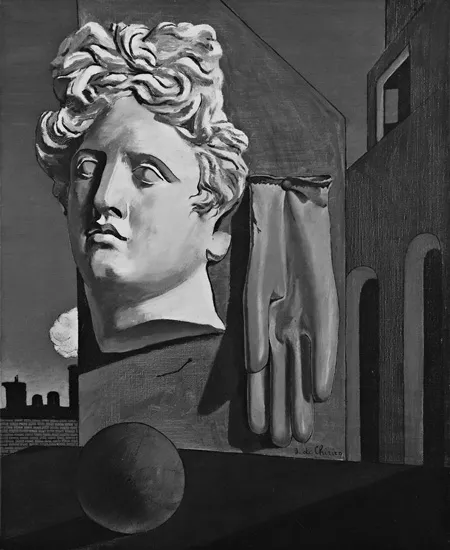

In the summer or fall of 1923, Belgian writer Marcel Lecomte, a member of the Belgian surrealist movement, showed Magritte a reproduction of Giorgio de Chirico’s Le chant d’amour (The Song of Love), 1914 (fig. 1.1).

Although the exact chronology and facts of the now legendary episode are uncertain, Magritte’s “discovery” of the metaphysical paintings of de Chirico is universally accepted as a pivotal event, though often noted without further elaboration. Art historians have credited the Italian’s paintings (along with Max Ernst’s collages) with Magritte’s rejection of abstraction and his initiation into surrealism, noting that Magritte borrowed and transformed de Chirico’s iconography—his mannequin, classical statuary, and spherical forms. But for Magritte there was more to de Chirico than an evocative array of symbolic forms. While Magritte later could not recall the exact objects in The Song of Love, he did remember what had moved him so powerfully about the painting:

This triumphant poetry supplanted the stereotyped effect of traditional painting. It is a complete break with the intellectual habits peculiar to artists who are prisoners of their talent, virtuosity and all petty aesthetic frills. It is a question of a new vision in which the viewer rediscovers his isolation and hears the silence of the world.10

De Chirico’s “new vision” transformed ordinary volumetric objects, through distortions of scale and perspective, to induce a deeply felt and existential sensation. No longer a window onto the real world, nor an abstraction, painting was a dreamlike and enigmatic expression of the depths of the human mind.

Fig 1.1 Giorgio de Chirico, Le chant d’amour (The Song of Love), June–July 1914. Oil on canvas, 73 × 59.1 cm. The Museum of Modern Art. Nelson A. Rockefeller Bequest. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY © 2017 C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Song of Love presents the uncanny juxtaposition of a rubber surgeon’s glove, a massive classical sculptural head, an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title page

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Plates

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Bringing Thought to Life

- 2 The Use of Speech in Painting

- 3 The Mystery of the Visible

- 4 Inspired Thought

- 5 Conclusion: Ends and Endings

- Selected Bibliography

- Index