Town plan analysis

The morphological idea was introduced to geography by Carl Ritter (1779–1859) for the study of the forms and structure of the landscape, which was considered to have an organic quality (Sauer 1925). In an essay on Deutsche Stadtanlagen (the layout of German towns), published in 1894, Johannes Fritz used town plans to compare the physical forms of urban areas. It is evident that empirical field-based research underpinned his plan analysis (Larkham and Conzen 2014). Fritz delimited the different layouts (street layouts in particular) of which the city of Rostock was comprised. Though crude, it exemplifies the beginning of a potentially important research activity that is often referred to today as morphological regionalization: the recognition of the way in which urban landscapes are structured into unitary areas (Whitehand 2014a). Recognizing such unitary areas is not only part of the activity of discovering how urban landscapes are composed but also fundamental to the planning and design of what should happen to those landscapes in the future (Whitehand 2014b).

The research of morphology started to take shape as an organized field of knowledge at the end of the nineteenth century. Some of its most important roots were in the work of German-speaking geographers, such as the geographer Otto Schlüter, who proposed the city as part of the wider landschaft (landscape). He had published two papers: a programmatic statement about settlement geography in general and kulturlandschaft (cultural landscape) in particular (Schlüter 1899), and a second paper about the ground plan of towns. He drew heavily on an earlier paper by Johannes Fritz’s Deutsche stadtanlagen and reproduced from that paper a number of simple maps of the layout of German towns. Though they were merely descriptive in nature, essentially diagrams of street patterns delimited on the distinct physical parts into which the historical cores of the towns could be divided, they emphasized the interdependence in geography of form, function, and development, with a particular focus on stadtlandschaft (urban landscape) as distinct from the rural landscape. These were early examples of tracing the historical development of urban form that was in the next century to become a primary feature of urban morphology. Enriched by the contributions of architects (e.g., Siedler 1914) and historians (e.g., Hamm 1932), this approach was later referred to as morphogenetic.

A key feature of the morphogenetic approach from its early days was the mapping of the various physical forms within urban areas. The geographer Hassinger (1916a,b) probably pioneered the practice of plotting the map in color. He followed Fritz’s interest in street plans by mapping buildings according to their architectural periods. Hassinger (1916b) detailed the historical architectural styles in the city of Vienna based on Walter Geisler’s major work in inner Danzig (Gdansk), culminating in comprehensive classifications of the sites, ground plans, and building types of German towns (Geisler 1918). These early works recognize that a city is an extremely complex object, and their maps reflect a hierarchical view of the city, structured according to a set of fundamental physical elements (Oliveira 2016).

It is noted that morphology has critical links with several disciplines including the Berkeley school of cultural geography established by Carl Sauer (Whitehand 2007). In terms of literature, there was considerable scrutiny of aspects of urban morphology within German-language publications. The most succinct review of the field in its early years is a 1930 paper on the state of urban geography by Hans Dörries. The monograph on Vienna by Bobek and Lichtenberger (1966) is also a prominent example. In more recent decades, Vance’s (1990) book entitled The Continuing City introduces the morphology in Western civilization, while Remy Allain’s (2004) Morphologie Urbaine is notable in French. Both books propose that the characteristics of urban structure include morphogenetic method, cartographic representation, and terminological precision.

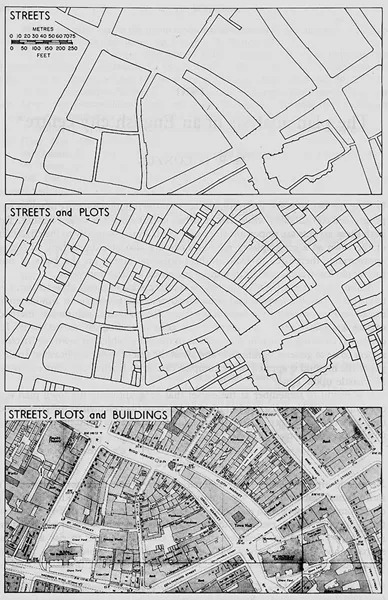

Kropf (2009, 2011) rephrases morphology as urban tissues to illuminate the character of a city. Urban tissue is defined as an organic whole that can be seen according to different levels of resolution, each corresponding to different elements of urban form. The higher the level of resolution, the greater the detail of what is shown and the greater the specificity of morphological description. At a very low level, urban tissue encompasses only the visible streets, while, at a high level of resolution, it might include a number of details, such as the construction materials of an open space or building. Kropf’s argument is that urban form should pay attention to the internal transformations of urban tissue and the combinations of urban tissue in the process of polymorphogenetic accretion.

Town plan analysis has been mainly developed by the Anglo-German geographical school associated with M. R. G. Conzen. The application of this analysis to the urban landscape originates with Schlüter’s (1899) papers, published in the late nineteenth century, which call for the detailed description of the visible and tangible forms on the ground and their genetic and functional explanations in terms of the actions of man in the course of history and in the context of nature. From the beginning, Schlüter envisaged the development of an explanatory morphology that is fully aware of the interdependence in geography of the three traits of form, function, and development (Whitehand 2007).

In assessing the key factors at the intra-urban scale, the historical expressiveness of urban landscapes merits particular attention. Its importance and how it might be approached within urban planning were initially addressed by Conzen. In a University of Berlin dissertation, Conzen (1932) mapped the building types in 12 towns in an area to the west and north of Berlin. Different colors denoted different types of buildings, while differing color depths indicated the number of each building’s storeys. Later, Conzen (1958, 1962) used a similar approach to produce his better-known maps of the English port town of Whitby. In his map of the building types, priority is given to historical periods, which he conceptualizes as morphological periods marked by a unity of physical forms. Conzen (1966: 56–61) observed the difficulty that British society was having in the cultural crises of the early postwar decades, and decided to “keep its sense of continuity and its capacity to see things interconnected,” a problem reflected in uncertainty in the grasp of long-term values. He repeatedly stressed the importance of a physical environment of the fullest possible historical expressiveness in enabling the individual to put down roots in an area, demonstrating the historical dimension of human experience and thereby stimulating comparison in a more informed way of reasoning. He further argued that “the state of the cultural landscape and in particular the preservation or neglect of its historicity reflects closely the average cultural consciousness of that society and thus indirectly the long-term efficiency of its education system.” It was Conzen who put forward a tripartite division of urban form into (1) the town plan, or ground plan (comprising the sites, streets, plots, and block plans of the buildings); (2) building fabric (the three-dimensional form); and (3) land and building utilization (Conzen 1960: 4). He expounded the tripartite division for giving high priority to historicity and went on to set out a method whereby it could be incorporated into urban planning.

The most famous proponent of town plan analysis is Conzen’s book (1960) entitled Alnwick, Northumberland: A Study in Town-Plan Analysis, which ultimately led to the development of the Conzenian School in the UK. In his book, Conzen subdivided the town of Alnwick for analytical purposes into streets and their arrangement in a street system, plots and their aggregation into street blocks, and buildings, or more precisely their block plans (Whitehand and Larkham 1992). The constructs Conzen applied to describe these subdivisions, such as “plan units,” “morphological periods,” “morphological regions,” “morphological frames,” “plot redevelopment cycles,” and “fringe belts,” are still in use in the study of urban morphology (see Figure 1.1). Conzen’s contribution to a historico-geographical approach on urban form can be summarized in five major points: (1) the establishment of a basic framework of principles for urban morphology; (2) the adoption for the first time in English-language geographical literature of a thoroughgoing evolutionary approach; (3) the recognition of the individual plot as the fundamental unit of analysis; (4) the use of detailed cartographic analysis, especially employing large-scale plans in conjunction with field surveys and documentary evidence; and (5) the conceptualization of developments in the townscape (Whitehand 1981).

One of the concepts raised by Conzen was the burgage cycle, in which the progressive built occupation of the back of the plot culminates in a significant reduction of open space, resulting in the need to release this space and in a period of urban fallow, which, in turn, precedes a new development cycle (Oliveira 2016). Burgage is a medieval land term used in England, which means a town (borough) rental property owned by a king or lord. Conzen deftly utilized the burgage cycle in the case study of Alnwick, but this phenomenon quickly gained attention from other urban morphologists, who applied it to additional contexts. These can be subjected to metrological analysis, which affords an important means of reconstructing the histories of plot boundaries (Lafrenz 1988). For example, by analyzing measurements of plot widths in the English town of Ludlow, Slater (1990) was able to detect regularities, speculate about the intentions of the medieval surveyor when the town was laid out, and infer the original plot widths and how they were subsequently subdivided, while Oliveira (2016) observed that the city of Porto in Portugal carries a similar developmental cycle. The burgage cycle conceptualizes a process of plot occupation and construction of working-class housing in the back of the bourgeois building facing the streets, without changing the plot structure. A period of “urban fallow” prior to the initiation of a redevelopment cycle is a particular variant of a more general phenomenon of building repletion where plots are subject to increasing pressure, often associated with changed functional requirements, in a growing urban area.

Perhaps the most significant ideas are the concepts of the plan unit and the fringe belt, around which a considerable amount of research has subsequently been constructed. Conzen (1960, in Whitehand 1981: 14) defines a plan unit as “examination of the town plan shows that the three element complexes of streets, plots and buildings enter into individualized combinations in different areas of the town.” Each combination derives uniqueness from its site circumstances and establishes “a measure of morphological homogeneity or unity” in some or all respects over its area. It represents a plan unit, distinct from its neighbors. A basic characteristic of a plan unit is that it exists as a specific component of an urban area. Baker and Slater (1992: 49) explain that

areas exhibiting a “measure of morphological unity” may be defined at very different scales from the whole intra-mural area down to a minor plot series. Further, in some cases, characteristics which distinguish an area from its neighbors may not be uniformly present throughout that area.

In Baker and Slater’s discussion, plan units can vary in size and be assigned sometimes even with a vague boundary around it. To identify and investigate plan units is an important basis of other town plan analysis approaches, such as morphological period, regions, frame, and fringe belts. It is a preliminary step to comprehending a city or town as a complex of wholeness.

The most widely quoted concept in Conzen’s town plan analysis is the fringe belt, which is defined as

the physical manifestations of periods of slow movement or actual standstill in the outward extension of the built-up area and characterized in the initial stages of their development by a variety of extensive uses of land, such as various kinds of institutions, public utilities and country houses, usually with below average accessibility requirements to the main part of the built-up area.

(Conzen 1960)

Regarding the physical forms, Conzen (1966) stresses that the major significance in the formation of a fringe belt is the existence of a fixation line, defined as the site of a strong, often protective linear feature, such as a town wall marking the traditional stationary fringe of an ancient town. In Whitehand’s study (1988: 48), the sequence of fringe belt development may be divided into two principal phases. The first phase, fringe belt formation, occurs when land at the fringe of the built-up area is taken up for the first time by urban or quasi-urban land uses. It continues until land under these uses no longer abuts on to rural land, and further development of the fringe belt by the addition of new plots at the actual fringe of the built-up area is thereafter precluded. The second phase, fringe belt modification, commences when the growth undergoes formation and modification phases. The purpose of the fringe belt concept is to explain and describe urban growth and transmission processes, and the value of this tool is to suggest and arrange appropriate new changes in evolutionary consequences. The fringe belt concept has been widely applied, particularly in study of the areas between the urban and suburban, and rural areas which usually are deemed “sensitive” and where more challenges and opportunities are concentrated.

Various directions have emerged in recent decades regarding the implementation of town plan analysis, and its importance to historical preservation and tourism development remains strong...