eBook - ePub

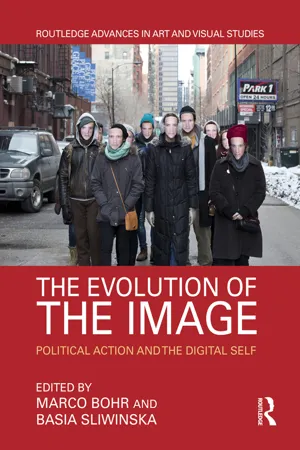

The Evolution of the Image

Political Action and the Digital Self

This is a test

- 154 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume addresses the evolution of the visual in digital communities, offering a multidisciplinary discussion of the ways in which images are circulated in digital communities, the meanings that are attached to them and the implications they have for notions of identity, memory, gender, cultural belonging and political action. Contributors focus on the political efficacy of the image in digital communities, as well as the representation of the digital self in order to offer a fresh perspective on the role of digital images in the creation and promotion of new forms of resistance, agency and identity within visual cultures.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Evolution of the Image by Marco Bohr,Basia Sliwinska in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Camera Phones and Mobile Intimacies

Note: All images made by the author on a camera phone (iPhone 6). All originals in colour.

It is remarkable that, beyond its function as a telephone, the ‘cell phone’ is essentially a pocket computer designed to do a multitude of other things at the same time. The cell phone is a device that creates a space for its user to conduct their social life, business duties and leisure interests, all united in one object-space that fits in a pocket/handbag. What is there to say about this device and the new practices it creates for its users? More specifically, what can be said about the phone camera and the impact of the new ‘phone photography’ it has enabled, now also linked to the Internet host sites and platforms that circulate and celebrate these images? And what of the fact that these digital images and the phone machines that produce them are part of a much bigger and broader apparatus of computational activity, of ‘big data’ systems, which, aligned with machine learning algorithms, help to organize and structure the impact and effects of all these machines on us? In short, the question here is: what are the effects of mobile phones on our subjectivity, our personhood and ‘lives’, given our new daily intimate relation with them? Or, reciprocally, what are the effects of users on the development of these camera machines and their images?

The invention of the portable cell phone long precedes the invention of the camera phone. The development of the camera phone has a very specific history. The camera was first introduced into the portable cell phone market during the year 2000, in Japan and South Korea. This makes the camera phone a specifically new ‘millennial’ device, born in the twenty-first century, which first emerged on the market in Asia.1 In 2002, these camera phones were rebranded, exported and sold in other cell phone market segments across the world. However, despite a billion cell phones already registered for use in 2002, it is generally considered that it is the widespread launch of the new 3G ‘third generation’ communication networks (eventually taken up more widely in the USA and European markets in 2004) that really made the significant difference to the popular use of the mobile phone in telecommunications culture.2 As Jon Agar notes in Constant Touch, ‘3G’ enabled a higher quantity and quality of data to be streamed, allowing for a more complex development and use of the cell phone.3 The 3G network, coupled with the almost incidental inclusion of text messaging and email in mobile phones – added as functions in an almost chance afterthought by the designers – suddenly meant that the phone was useful as a device for a more extensive set of purposes than simply a phone call conversation. Verbal communication could be supplemented by written messages as the possibility for ‘texting’ and emails became available. The mobile phone was quietly turning into a ‘multi-media’ tool, as a more widely useful device for communicating with other people. It was only a matter of time (and data memory increase) before visual communication would be added to the phone, its camera enabling this image function as supplementary media too. In fact, there was an attempt to name the early camera phone a ‘visual phone’. The mobile phone was rapidly and even perhaps somewhat unexpectedly plugged into a whole new world and network of mobile communication devices, currently ‘4G’. The rest, as they say, is history.

The technological battle, fought out during the 2000s, to improve camera phone technology was primarily between the ascendant Nokia and rival Sony Ericsson corporations, until they were both usurped by Apple’s introduction of the first iPhone in 2007. Since then, the popularity of the ‘smart phone’, with its convenient flat shape and size has levelled the technics of the camera phone. In the short passage of time of their existence, the camera phone and its images (in trillions) have become the most common global source of digital photo-image streamed and archived on devices around the world today.

Who could deny that the smart phone and its camera, with its sophisticated still/moving image functions, has not already had a massive cultural impact on everyone’s lives today, regardless of whether such a device is used personally or not? The camera phone is one of the central components in the visual representation of everyday contemporary life and part of its technological transformation. Camera phone images coupled to the global network of Internet-linked computer screens have flooded all of our online and offline cultural spaces. Images are uploaded and downloaded daily on a minute-by-minute, if not second-by-second, basis. Whether seen voluntarily or not, camera phone images of every imaginable form and content have appeared of almost any and every location and of every subject matter you can and cannot imagine. These same images can be seen on screens that are also looked at in almost any and every location you can think of too. These are the new habits of computerized phone photography. Yet what does this mean?

The camera phone is a hybrid device emerging from the combination of three older technologies: the telephone, digital photography and Internet computing. Each of these predates the invention and development of the camera phone, yet has also informed its technical development. The technical advances of the cell phone camera has followed work in parallel to the development of other digital cameras, computer chips, sensor designs, megabyte size and data image file formats. Camera phone technology drew on and advanced these digital imaging technology fields, but in miniaturized forms, adding mini lenses and micro flash functions to the technical developments of multiple exposure, face recognition, slow-mo(tion) ‘movie’ and burst modes; digital zooms as well as panoramic and HDR (high dynamic range) exposure modes. All these functions were and are developed for inclusion into a variety of smart phones across the market. As such, camera phone technology ‘shrank’ digital photography into becoming an essential component within almost any mobile phone or portable computer device. However, we may also note that, unlike most other digital cameras, camera phones have two lenses: one facing the user, like a mirror, and the other facing outwards, like a window. While these two camera lenses serve one camera phone, this nevertheless does not mean that they are the only two optical inputs possible for these devices. With its visual data screen, the camera phone can be used as a computer centre, as a remote-control console for another device, for example, to operate another camera shutter and lens, operating a satellite digital camera or other such device, like a hovering drone camera lens, through which one can also take aerial photographs or shoot a video.

The technical acceleration and transformation involved in the tiny technics of these camera phones, their screens and associated electronics have been truly astonishing. Pictures taken with them can be instantly streamed or uploaded to online sites and a variety of different network resources and platforms. These same images can then be re-sent or downloaded to other sites and platforms automatically. The remarkable technical achievement of this device is given in its popular name, no longer, as originally, a ‘cell phone’, but precisely in the dual meaning of the mobile phone and camera, whose novelty is precisely in its mobility as a camera and the images that it supplies. The mobility of these images is way beyond the dream of the old analogue photography. Not only do camera phones have a dynamic range that is far more sensitive to light than any film, they also outstrip its capacity for instantaneous distribution. The camera itself is almost invisible, light and portable, yet this pocket computer/camera phone can also store a vast archive of images in itself and on online links. How does the camera phone achieve all this?

Automation. The procedure for taking a camera phone image has been highly simplified technically for the user and this is one of the key features of the mobile phone camera. The process of taking a picture is an activity (technically) reducible to the user pointing the device at the subject and composing (or not) the image on its screen and triggering the shutter. Once triggered the phone processor automatically generates and stores the registered image as data on the device and/or can also automatically stream it to other designated locations for sharing, later selection and/or back-up as storage. The very mobility of these images means that the user is able to simply move an image from one space to another. In a mere gesture, the image can be ‘swiped’ from one screen to another very different location on another screen. All this ‘instantaneous’ mobility is achieved through a sophisticated level of technical automation in the processing of the image. It is this automation that gives the image as data its cultural ‘liquidity’.4 This same technical automation also enables the user to make images ‘without thinking’. The intentionality of the phone camera user can be given the same sort of status as doodling with a pen, i.e. taking pictures out of boredom, in any location with almost any lighting or other environmental conditions. Conversely, the specialist can use this automation as an intentional variation to the control of the professional, as an electronic form of surrealist ‘chance’. It is thus possible to make acts of visualization ‘instantly’, which demand no technical skills beyond a basic cultural knowledge of a photographic image, and the whereabouts of the ‘shoot’ button to operate the camera phone or other device. The automation and mobility of this type of image means that the user is able to produce pictures anywhere, anytime and anyhow, with or without any specific purpose. These characteristics release the camera phone user from the usual co-ordinates of behaviour and propriety defined as acceptable for a photographer. Instead of only taking a camera to photograph a special event and special occasions that make up most social and domestic photography (e.g. the scenes of vacations, the rites of marriage ceremonies, other family and friend gatherings and events), the phone camera is now ever present, in a handy pocket or bag, and can be operated at any time at all. Here is the birth of the so-called ‘citizen photographer’, who, like the professional news photographer of old, always has a camera to hand. Yet, instead of taking pictures to follow a specific brief or shoot schedule (as with the professional photographer), the new versatility of the camera phone means that its non-specialist user conducts a different activity; it is used as a witness to the experience of the self. This at least is the temptation, given the simplicity of the photographic act. The camera can be operated anywhere, in the kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, lounge, office, restaurant, bar, nightclub, car and bus and so on, in fact, wherever the user is located.

We can see some of these new behaviours al...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Camera Phones and Mobile Intimacies

- 2 Creepshots and Power: Covert Sexualised Photography, Online Communities and the Maintenance of Gender Inequality

- 3 Interview with Rasha Kahil: May 5th, 2017

- 4 Imagening Discontent: Political Images and Civic Protest

- 5 Mobile Places and the ‘Cyborg Body’: Feminine Embodied Net-community of #CzarnyProtest/ #blackprotest

- 6 Appearance Unbound: Articulations of Co-Presence in #BlackLivesMatter

- 7 Photography, Politics and Digital Networks in a ‘Post-Truth’ Era

- 8 Posthuman Photography

- 9 Smart [Phone] Filmmakers >> Smart [Political] Actions

- 10 Am I Seen? The Reciprocal Nature of Identity as Technology

- 11 The Future Evolution of the Image

- Index