A large portion of the population was greatly weakened by want; [and the 1877 drought] was followed in 1878 and 1879 by a dreadful epidemic of fever.

– Gurgaon District Gazetteer, 1884, p. 132

The multifaceted history of malaria illuminates fundamental aspects of human history.

– C.E. Rosenberg, ‘Foreword,’ in R. Packard, The Making of a Tropical Disease, 2007, ix

Little could the village chowkidars (watchmen) of the Indian subcontinent have known when they began reporting weekly deaths and births in the late 1860s to the local thana 1 offices of the British colonial administration that they were contributing to a body of data which would provide far-reaching insights into human health history.2 In recent decades the analytic importance of the South Asian vital registration records, based upon the reports of these low-status rural functionaries, has been increasingly recognised by historical demographers.3 This study of epidemic malaria history employs these data from one region of British India, gathered from the 36,000 villages and towns of the northwestern province of Punjab, to explore the impact of changes in food security on malaria mortality decline and beginning rise in life expectancy across the later colonial and early post-colonial period.

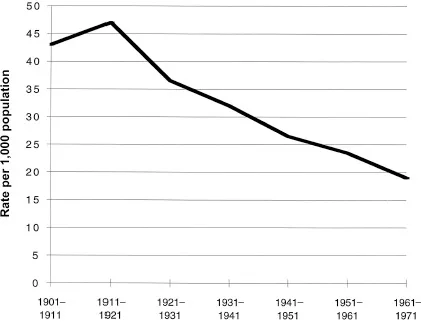

From the mid-19th century through to the early 1920s, mortality levels across much of India were extremely high, with life expectancy in the low to mid-twenties. Recurring famine and epidemic crises were reflected in low, or sometimes negative, demographic growth. Among these ‘epidemics of death,’ malaria figured pre-eminently, typically as a surge in autumnal fever deaths following the monsoon rains. This mortality profile began to change quite fundamentally from the early decades of the 20th century. Decline in mortality crises after 1920 brought a sustained, if modest, rise in life expectancy, a transition captured with some clarity in the provincial sanitary records, annual reports in which the vital registration data were published. Though the precise timing and extent of mortality decline differed among the major provinces of British India, by the third decade of the 20th century, a trend of increasing survival rates is evident for the Indian subcontinent as a whole (Figure 1.1).4

For more than a century following the late 19th century identification of specific disease microbes, demographic and epidemic historians have debated the relative roles of economic factors (rising living standards) versus environmental (sanitation/public health) and modern medical measures in explaining the secular rise in human life expectancy in the modern world. The question has been phrased roughly thus: to what extent has mortality decline resulted from changes in exposure to infectious disease (i.e., transmission of infection) and improved medical treatment, relative to the effect of rising human host resistance to disease through increasing food security?

Figure 1.1 Decadal crude death rate, India, 1901–1971

In a rather different form, this same question poses itself in the pages of the sanitary records of British India, here expressed as a quiet dichotomy running through the 80 years of vital registration records. One ‘voice’ prefaces each annual report with data on local (provincial) harvest conditions, price levels of staple foodgrains, and prevailing employment and wage rates, information sanitary officials deemed key to interpreting general conditions of public health (mortality) and epidemic patterns for the year. A second voice, within the body of these same reports, interprets epidemic patterns according to prevailing medical theories of disease transmission. Through much of the 19th century, for example, post-monsoon ‘fever’ mortality was explained in classic terms of ‘miasma’ – poisonous vapours emanating from rotting organic matter following the monsoon rains5 – an explanation which shifted seamlessly in the early 20th century to post-monsoon entomological conditions conducive to breeding of the malaria mosquito vector. Though separate, the two views, economic and miasmic- entomological, often came together at times of food crises, when sanitary officials described such fever epidemics in terms of ‘malaria merely reap[ing] a harvest prepared for it by the famine.’6

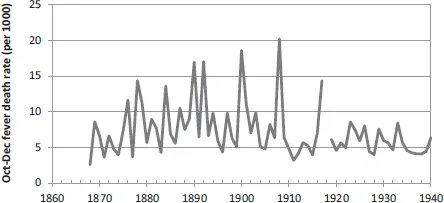

Both voices remained in the provincial sanitary ledgers and the burgeoning Indian malaria research literature through the final years of British rule to 1947. By the mid-20th century, however, the economic view had receded from the medical sub-discipline of malariology in India, and more completely so from the international literature. But by this point, so too had the virulent form of malaria: the severe epidemics and classic ‘saw-tooth’ pattern of mortality that had once featured so prominently on the South Asian vital landscape had markedly declined after 1920, including in Punjab, the region most ‘notorious’ in the Indian subcontinent for its epidemic malaria burden.7 Here, the abrupt cessation of malaria transmission with residual insecticide (DDT) spraying in the early 1950s would have only marginal impact on prevailing death rates in the post-Independence state, the historical epidemic mortality impact of the disease having been largely tamed four decades earlier with the political imperative of famine control (Figure 1.2).

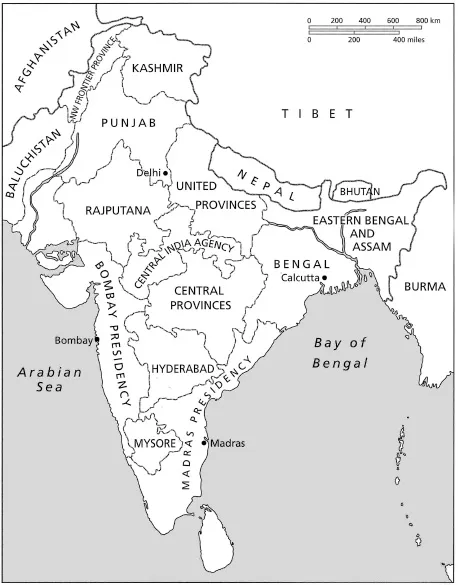

Such a picture of South Asian malaria history – the highly lethal form of the disease receding well before modern methods of malaria transmission control – is one at odds with current understanding of mortality decline in the post-colonial ‘developing’ world. Preoccupation with powerful new medical technologies of vector control that emerged in the immediate post-World War II era, combined with shifts in core epidemiological concepts and language relating to both disease and hunger over the preceding century, together have constrained analysis, and left the history of malaria mortality decline in the Indian subcontinent largely unrecognised and unwritten. This study is an attempt to reclaim some of this lost history. It seeks to understand more clearly the role of acute hunger in contributing to the so-called fulminant form of malaria in one corner of colonial India, Punjab province (Figure 1.3). It asks how this understanding came to be lost, and what a more complete South Asian malaria, and hunger, historiography can contribute to our understanding of human health history. It is perhaps fitting, if ironic, that the illiterate village chowkidars, who often came from the least food secure, low- or out-caste sections of their communities, should have provided the data essential to recovering this history.

Figure 1.2 Mean annual Oct.–Dec. fever death rate, 23 plains districts, Punjab, 1868–1940

Significance of ‘Malaria in the Punjab’ (1911)

In September 1911, the Indian government formally released the results of an official inquiry conducted two years earlier into the causes of the 1908 malaria epidemic in Punjab province, an epidemic which in the space of three brief months had left 300,000 people dead and brought the economy of this northwestern region of the subcontinent to a standstill. The determining causes of the epidemic, Major S.R. Christophers concluded in his cautious but comprehensive report, Malaria in the Punjab, were ‘excess rainfall and scarcity… . [T]he former is an essential, whilst the latter is an almost equally powerful influencing factor.’8

That malarial fever was associated with the annual monsoon rains was hardly a new revelation within the echelons of the British Indian sanitary administration. Long before Ronald Ross’s 1897 confirmation of the role of mosquitoes as vector in malaria transmission, the relationship between malarial fever and the yearly monsoon rains had been evident to colonial officials, interpreted as triggered by ‘miasmatic’ vapours from rain-soaked soils. In the semi-arid northwest plains of Punjab, a region where annual malaria transmission was sharply limited to the immediate post-monsoon period, this relationship was all the more evident. More remarkable in the inquiry’s conclusions, by contrast, was the prominence given to economic conditions.

In the delicate political climate of the British Raj at the turn of the 20th century, Christophers’s choice of terms was assiduously circumspect. The word ‘starvation,’ or indeed even ‘hunger,’ would appear nowhere in his 135-page inquiry report. Yet in referring to ‘scarcity,’ Christophers left little doubt about the meaning intended. A key administrative term, the word referred to market foodgrain prices sufficiently high to be predictive of famine, a designation upon which the entire colonial famine relief apparatus hinged. Indeed, one entire chapter of his report would be dedicated to the ‘human factor’ in epidemic malaria causation. Here Christophers chronicled in quantitative detail the influence of ‘physiological poverty’ triggered by high foodgrain prices. ‘It became evident, as the enquiry proceeded,’ he would observe with characteristic understated precision,

that a full dietary, as understood by the well-fed European, falls to the lot of but few of the poorer classes, and that in times of scarcity these are accustomed to adapt themselves to circumstances by proportionately restricting the amount of the food they take.9

Tucked quietly into the text of the 1911 report, this observation bore profound implications for British Indian rule. It was, in effect, explicit acknowledgement of the lethal impact of episodic soaring prices (‘scarcity’) which increasingly had been triggered by the entry of Indian foodgrains onto the international grain market over the preceding half-century.

Malaria in the Punjab is a remarkable document for many reasons. Some relate to the study itself; others, to the larger importance of malaria in the region’s health, demographic, and political history. Epidemiologically, the report is the most rigorous analysis of epidemic malaria ever conducted in India, a quantitative investigation of not a small localised malaria ‘outbreak,’ but rather of a vast regional epidemic extending over a territory of some 100,000 square kilometres.10 The study is remarkable also in that it was conducted scarcely a decade after Ronald Ross’s elucidation,11 in southern India, of the mosquito as vector in malaria transmission. Exploration of the complex microbiological factors underlying malaria transmission, though still in its early stages, already dominated malaria research, and in this work Christophers was a leading figure. Malaria in the Punjab, and his previous work at the Punjab military cantonment at Mian Mir, would in fact lay much of the foundation of modern entomological and epidemiological understanding of the disease.

Key to the study’s analytic rigour was Christophers’s use of the province’s vital registration data. Systematic recording of monthly deaths in the towns and villages of Punjab dates from 1867. Deaths, and from the early 1880s also births, were reported weekly by the village chowkidar to the nearest thana police station,12 and there compiled in monthly statistics recorded under a limited range of disease categories that included smallpox, cholera, ‘fever,’ ‘bowel complaints,’ and later plague. If not entirely complete, reporting in Punjab province by the final decades of the 19th century had attained remarkably high levels. In some districts such as Ludhiana, coverage was estimated at 93 to 97 per cent by the turn of the century.13 The annual sanitary reports thus represent a unique data series, one spanning many decades of extremely high, pre-demographic-transition mortality levels, and continuing across the post-1920 period of South Asian mortality (crude death rate) decline.

Cause-of-death data contained in the annual sanitary reports, on the other hand, were much more problematic. Often half or more of all deaths were recorded ...