- 558 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Diachronic and Comparative Syntax

About this book

This book brings together for the first time a series of previously published papers featuring Ian Roberts' pioneering work on diachronic and comparative syntax over the last thirty years in one comprehensive volume. Divided into two parts, the volume engages in recent key topics in empirical studies of syntactic theory, with the eight papers on diachronic syntax addressing major changes in the history of English as well as broader aspects of syntactic change, including the introduction to the formal approach to grammaticalisation, and the eight papers on comparative syntax exploring head-movement, the nature and distribution of clitics, and the nature of parametric variation and change. This comprehensive collection of the author's body of research on diachronic and comparative syntax is an essential resource for scholars and researchers in theoretical, comparative, and historical linguistics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Diachronic Syntax

1

Agreement Parameters and the Development of English Modal Auxiliaries*

1. Introduction

1.1 General Background

- (1)

a. Inversion: Must they leave? *Leave they? b. Negation: They cannot walk. *They walk not. c. Agreement: *He mays, musts, wills, cans, etc. d. Non-finite forms: *He has (?)might (etc.) to do it. *They are canning to do it. *They might could do it.2

- (2)

- Inversion:

- (i) Al her cariage was stole be the Frenshmen, so mote they nedes go home on fote All their conveyance was stolen by the Frenchmen; so they had to go home on foot.(c. 1464 Capgrave Chronicle of England: V 1694)

- (ii) Wilt thow ony thinge with hym?Do you want him for anything?(1470–85 Malory Morte d’Arthure III, iii, 102, V 559)

- (iii) Than longen folk to goon on pilgrimages Then people want to go on pilgrimages. (c. 1386 Chaucer General Prologue Canterbury Tales, 12)

- (i) Al her cariage was stole be the Frenshmen, so mote they nedes go home on fote

- Negation:

- (i) ʒif ʒe wollnot to haue mercy of God If you don’t want God’s mercy.(c. 1450 Mirk’s Festial 285: V 1177)

- (ii) Thy godfadirs wyff thow shalt not take You shall not take your godfather’s wife. (c. 1450 Idley Instructions 2 a. 1757: V 1489)

- (iii) A blynde man kan nat juggen wel in hewis A blind man cannot judge colours well. (c. 1387 Chaucer Troilus 2, 21: V 1624)

- (iv) He ne held it noght He did not hold it. (Mossé, 1952, p. 112)

- (v) My wyfe rose nott My wife did not get up.(Mossé, 1952, p. 112)

- (i) ʒif ʒe wollnot to haue mercy of God If you don’t want God’s mercy.

- Inversion:

- (3)

- (i) I shall not konne answere

I will not be able to answer.

(c. 1386 Chaucer Canterbury Tales B 2902: V 1649) - (ii)Cunnyng no recour in so streit a neede

Knowing no recourse in so desperate a need.

(c. 1439 Lydgate Fall of Princes 7, 1346: V 1650) - (iii) if we had mought conuenient come together

If we had been able to meet conveniently.

(c. 1528 St. Thomas More Works 107, 86: V 1687) - (iv) if he had wolde

If he had wanted to.

(1525 Ld. Berners, Froiss. II, 402: V 1687)

- (i) I shall not konne answere

1.2 Theoretical Background

- (4) S ® NP INFL VP

1.2.1 Government

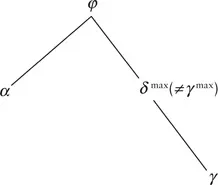

- (5)α governs γ in a configuration like [β … γ … α … γ …] where:

- (i)α = X0 (a lexical element)

- (ii)where φ is a maximal projection, if φ dominates γ, then either φ dominates α, or φ is the maximal projection of γ

- (iii)α c-commands γ.

(from Belletti and Rizzi, 1981, p. 12).

- (6)α c-commands β iff the minimal maximal projection dominating α also dominates β.

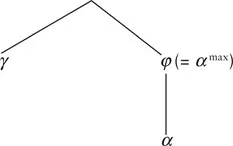

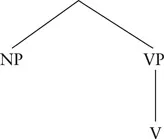

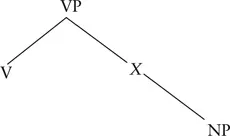

- (7)

- (i)φ is the minimal maximal projection dominating γ, as in (8):

- (8)

- (8)

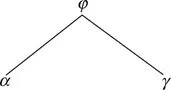

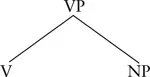

- (ii)φ is the minimal maximal projection dominating the maximal projection of γ:

- (9)

- (9)

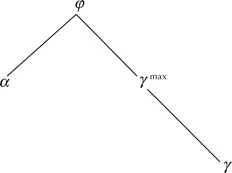

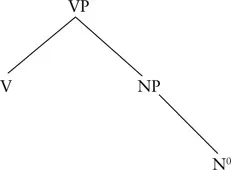

- (iii)γ is more deeply embedded inside φ than in either (8) or (9):

- (10)

- (10)

- (7′)

- (8′)

- (9′)

- (10′)

- (11) In a word of the form [w Stem +Af]:

- Af subcategorizes for the stem;

- Af heads W.

- (12)*outP + alA *carryV + alA*fortunateA + alA.

- (13)[transformation + al]A [industry + al]A[nation + al]A.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- PART I Diachronic Syntax

- PART II Comparative Syntax

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app