- 188 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Discovering Babylon

About this book

This volume presents Babylon as it has been passed down through Western culture: through the Bible, classical texts, in Medieval travel accounts, and through depictions of the Tower motif in art. It then details the discovery of the material culture remains of Babylon from the middle of the 19th century and through the great excavation of 1899-1917, and focuses on the encounter between the Babylon of tradition and the Babylon unearthed by the archaeologists. This book is unique in its multi-disciplinary approach, combining expertise in biblical studies and Assyriology with perspectives on history, art history, intellectual history, reception studies and contemporary issues.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Beginning discovery

Touring Babylon, the year 2000

The landscape flickered by, shifting between wastelands of dry desert shrubs, golden terracotta villages, palm trees and leafy bushes lining rivers and channels, as well as occasional greenhouses and gardens. Shepherds in long, dusty tunics and head coverings sought cover from the scorching sun, crowding with their sheep under the small shade of the palm trees. Children were on their way to school, some playing soccer at the roadside. Everywhere, people laid out bricks to dry in the baking sun and piled them high onto pallets. The smoke from countless brick factories drifted along and mixed with the fine-grained yellow air. Just like in ancient Babylon, I thought, watching the scenes from my velvet-covered seat in an oversized old tour bus.

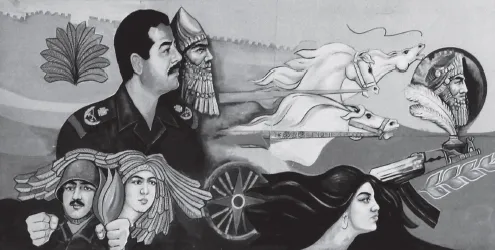

Just before reaching the site of the ruins, we stopped at an elaborate mural that had been raised up on columns, so it could be seen from a distance. Painted in bright colors, it depicted Saddam Hussein as King Nebuchadnezzar, flanked by modern weapons and ancient chariots (see Figure 1.1).

I was overwhelmed and embarrassed by this blatant show of power; a 20th century, brutal despot depicting himself as one of history’s great empire builders on what was essentially a roadside billboard. It seemed pompous, even comical. It defied my expectations.

We entered the actual ruins through a reconstructed copy of the Ishtar Gate, which I had not heard of before. Even though the gate was not authentic it created a focal point and gave off an impression of Babylon that seemed in harmony with the ancient ruins. The gate opened into a courtyard with a souvenir store and tourist information booth. From there, the guide took us first to a fenced-off area containing the main street from King Nebuchadnezzar’s time, the famous Processional Way (see Figure 1.2). It was still partially covered by the original natural asphalt. Perhaps the Israelites walked here when they were brought into exile? I wondered, feeling the grit under the soles of my shoes. Only later did I learn that this road was used to parade the Babylonian god Marduk to his temple during the great Akitu festival, and that it was called Aiburshabu.

The Processional Way led to the remains of the genuine Ishtar Gate. Even in this crumbling and abandoned state, the scale of the gate was staggering. It easily constituted a whole building with several chambers. Layer upon layer of fortification walls roared with reliefs of bulls and dragons. Originally the gate had stood a full level above what now remained, but German archaeologists took away the upper level when they excavated the area in the early 20th century, our guide explained. The Ishtar Gate had been just one of several gates in this city. There was no doubt that the city had been well protected and that any ancient visitor would have been impressed.

Figure 1.1 Saddam Hussein as Nebuchadnezzar, Babylon, Iraq.

Photo: Rannfrid I. Thelle, 2001.

Figure 1.2 Remains of the Processional Way at the Site of Babylon.

Photo: Rannfrid I. Thelle, 2001.

Our tour continued to the remains of a building with countless arches—the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Not all historians agree that this space was used to host an ornate garden of trees, shrubs, and flowering plants. Some speculate that it may have simply have contained storage facilities. I, like many others, may have heard about the Hanging Gardens as one of the seven ancient wonders, but only now, standing inside its shell thousands of years after they had been used for whatever purpose, did I realize how much they must have contributed to the city’s fame.

The only sculpture in the ruins of Babylon was a gigantic basalt statue of a lion standing above a man. This was the only artifact the Germans had not seized, which gave it symbolic significance for Iraqis. Beyond the lion, one of Saddam Hussein’s notorious palaces rose up on a hill, a stark reminder of what lay outside of the walls of Babylon.

After passing through several narrow hallways, we emerged into King Nebuchadnezzar’s Throne Room, the center of power of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This was where Belshazzar had seen the “writing on the wall”, as the book of Daniel reports. This was where Alexander the Great died. This is where history was born.

We were not shown the Tower of Babel. Instead, we journeyed on to the crumbled remains of a temple tower—a ziggurat—in Borsippa, around five miles (eight kilometers) from Babylon. It looked like a mound with two columns rising up out of the center, like a core. A fire had destroyed the Tower in antiquity, and melted the tar that held the bricks together. Later, I learned the foundation of an enormous ziggurat does exist among Babylon’s ruins. This tower had also been gone for several hundred years. Why it was not a part of the tour, I have never found out.

I arrived with a particular set of expectations on this first visit to Saddam Hussein’s Babylon. But this was not my first encounter with Babylon. In my reading of the Bible, I have stood next to the Tower of Babel and heard the cacophony of confused tongues. I have witnessed the tragic exile of the Jews to Babylon and Nebuchadnezzar’s ruthless destruction of Jerusalem. As a child, I participated in It’s Cool in the Furnace, Buryl Red and Grace Hawthorne’s musical about the crazy King Nebuchadnezzar who threw the young Jewish men, Shadrak, Meshak, and Abednego, into the fiery furnace. In their plaintive song about leaving Jerusalem, they had to learn to live in a new and different way. I have sung along with The Melodians—By the rivers of Babylon/where we sat down …—to their music inspired by the biblical Psalm 137 about the Jewish people sitting by the rivers of Babylon, weeping because they could not sing the songs of their homeland while in exile. From the history of Christianity, I knew of Martin Luther’s attack on the Catholic Church in the polemical pamphlet “The Babylonian Captivity of the Church”.

In present-day Iraq, it is not possible to find “ancient Babylon”. That did not stop me from romanticizing the ruins rising out of the sand. My expectations reached into the sky, and the reality paled in comparison. That smarting disappointment made a deep impression, but also left a new itch: what, then, was Babylon? Fueled by the desire to find out, my first encounter with the physical remains of Babylon set me on the path of a journey beyond my imagination.

In pursuit of Babylon

Ancient Babylon’s influence is visible throughout Western cultural history. But its former greatness could not shield it from the erosion of its reputation. Shaped in part by the stories of the Bible and in part by the records of the Greeks, Babylon’s reputation as a city of excess and evil took over after the metropolis had fallen. Babylon lived on through the Middle Ages in the images and symbols of the Christian Church and culture, as well as in traditions of biblical commentary. When texts from ancient Greece were rediscovered in the Renaissance, these descriptions of Babylon fed the ideas of Babylon’s opulence and arrogance. In art, theology, and literature, the city is the symbol of decadence, a repressive empire, a place of sin—a city doomed. Babylon became synonymous with the enemy, “the other”. However, alongside these negative images of arrogance and decay, the city has also inspired positive expectations, the dream of utopia, and the pinnacle of human achievement.

The 19th-century European discovery of Assyria and Babylonia is a tale of hard work and great effort, mixed with luck and coincidence, and seasoned with strong assumptions. The explorers bore with them the Enlightenment ideals of universal knowledge, the political ambitions of the fledgling nation states, and an attitude of entitlement. These cultural attitudes, coupled with unwavering faith in the cultural superiority of Europe, propelled European discoverers and scientific expeditions around the world to measure, collect, draw, count, and describe. British, French, and later North American and German explorers pillaged the mounds of Assyria and Babylon to hoard treasures for their national museums.

Modern Europe was beginning to unearth the past. Egypt burst with magnificent ruins that dazzled Napoleon and that his delegation could spot as they journeyed up the Nile in 1798: the pyramids, the Sphinx, temples, colossal statues, and tombs. Greece and Rome had left behind visible relics all over Turkey, Syria, and on the Greek islands. Even ancient Persia’s foundations weathered time. Yet Assyria and Babylon were literally buried in the earth. Was there any proof that these civilizations were more than just whispers passed down through generations?

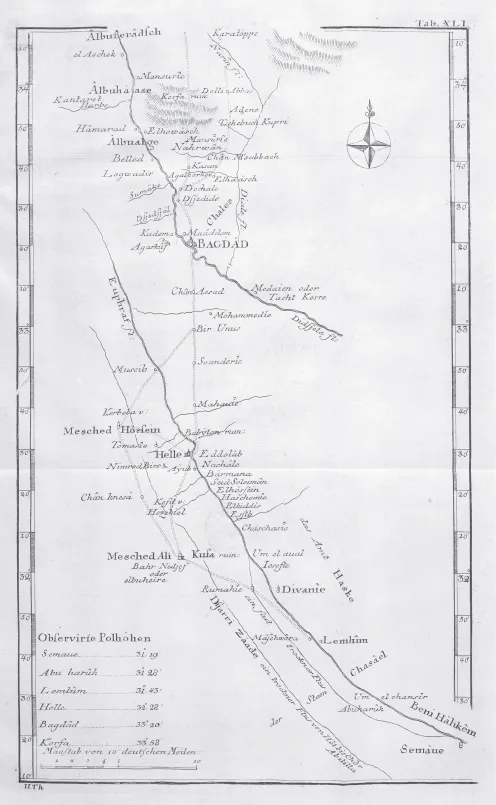

Almost 40 years before general Napoleon Bonaparte set out on his campaign into Egypt, a delegation on behalf of King Frederik V of Denmark–Norway departed on the first scientific expedition across Western Asia in January 1761. The only person who would survive this journey was the young Saxon, Carsten Niebuhr, who returned almost seven years later. Niebuhr published his first descriptions of the trip in 1772. The maps that he drew of the Red Sea, the Arabian Peninsula, and other areas were used for the next 100 years and became the basis for several new trade routes to India. Niebuhr measured exact coordinates for the ruins of the city of Babylon, mapping the city for the first time, and bringing the legend of Babylon out of myth and into present-day time and space (see Map 1.1).1

Niebuhr journeyed through Egypt, then across to Arabia, onward to India, and back overland through Persia, Mesopotamia, Syria, Cyprus, Palestine, and Turkey. In Mesopotamia Niebuhr discovered monuments decorated not only with drawings, but with a number of signs consisting of small cone-shaped lines. He believed these to be a written language. Niebuhr also documented the Behistun Inscription, a relief consisting of three different written languages, each in the same script, chiseled into a limestone cliff. The inscription became crucial for deciphering Old Persian, Elamite (another Persian language), and Babylonian. These discoveries spurred an adventure that led to the excavations of the Assyrian and Babylonian cities.

After lying buried in the ground for over 2000 years, the remains of Babylon were dug up by archaeologists around 100 years ago. European imperialism was at its peak, the status of the Bible as a major source of Western history was in serious jeopardy, and racial theories formed the basis for new perspectives on cultural history.

The discovery of Babylon is a story of rising empires and the explorers and archaeologists who moved the earth with their hands, as well as the officials who signed off on missions and stocked museums with the returns. It is about historians and theologians, and public controversies about the origins of cultures and the influence of the Bible. But it is also a story about ourselves and a 2000-year-long history of interpretation. The Babylon of the Bible and of Western culture was transmitted through the centuries in visual art, literature, theology, and a whole universe of meaning. When the ruins of Babylon were unearthed by explorers and archaeologists, it took place in a particular context that influenced how the findings were viewed. Together we will closely explore this tension between the inherited concepts and new knowledge. Is it possible to interpret anything anew, or are we always at the mercy of the dominant contemporary paradigms and personal perspectives?

From the first moment, the newly discovered Babylon attracted great interest. The wealth of new knowledge about ancient Babylon, with its highly developed culture older than ancient Greece and biblical Israel, irrevocably changed the European idea of Babylon. Yet, in spite of the enthusiasm over all that was new, even the most visually sensational finds failed to dislodge the almost mythical notion of Babylon that each successive generation had created. It was as if a new Babylon became known, but the old remained just as relevant.

Babylon continues to fascinate us. Even though the old conceptualizations may no longer be dominant in contemporary culture, Babylon continues to exist: as the ship called the Nebuchadnezzar in the film The Matrix, the web-based translation program “Babylon”, in pop culture songs, in the titles of novels, or in a constant flow of new renderings of the “Tower of Babel”. Our imaginations are challenged and express themselves in the need to build ever-taller buildings and towers, whether it is in Dubai, Shanghai, or New York. Babylon has become a useful metaphor when describing opponents and enemies with their hungry power ambitions, their evil and decay.

Map 1.1 Carsten Niebuhr’s Map of Mesopotamia.

Which is the “true Babylon”? Is it the Tower of Babel and the evil empire, or is it the Ishtar Gate and the Processional Way with their religious significance and architectural beauty? The truth is that “Babylon” is always changing, and that we are constantly rediscovering and recreating history. When the German excavation began in 1899 and new knowledge about the city was finally available, the British historian Leonar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures

- Maps

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Credits for figures and maps

- 1 Beginning discovery

- 2 Biblical Babylon

- 3 European visions of Babylon

- 4 Ad fontes? Babylon of the Greeks

- 5 The discovery of Mesopotamia

- 6 From the sources of Babylon

- 7 Babel and Bible

- 8 Babylon’s resurrection

- 9 Back to the future

- Appendix 1: Ancient literary and historical texts mentioned

- Appendix 2: Deities of ancient Babylon

- Appendix 3: Timeline of Babylon in relation to contemporary and later cultures

- Appendix 4: Important years in Babylonian history Neolithic Age

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Discovering Babylon by Rannfrid Thelle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.