Introduction

The issue of how the specialists in legitimate organized violence ought to and do relate to the society they are supposed to protect and to those who rule it, is at least as old as political thought itself: one finds it raised in Book III of Plato’s Republic. It was long dealt with in terms which restricted it to one single question: how to secure the full subordination of de facto military power to legitimate, sovereign political power? This strongly suggests that such a problem is not specific to liberal democracies alone: that it in fact derives from the nature of things.1

This was Clausewitz’s message when he emphasized the intrinsically political nature of any resort to force, i.e., the notion that military force cannot be an end in itself, and that what counts is the political landscape which its use, or even its mere existence, are apt to fashion. Such theoretical justification of civil control in the domain of external relations finds its internal counterpart in the nature of sovereign political power as the ultimate arbitrator among competing values, interests or manifestations of power within the polity. It follows that armed forces, standing for security-related interests and values that vie for attention and resources with those of economic prosperity and sociopolitical harmony, are in essence but one tool among others in statesmen’s hands; it follows also that their possible transformation into autonomous political actors can only be regarded as an aberration fraught, in many historical cases, with dire consequences.

That such has been the case across periods, places and regimes, and not only under conditions prevailing in liberal democracies, is convincingly borne out by the fact that absolute monarchs, dictators or totalitarian leaders have been quite as anxious as democratic rulers, if not actually more, to enforce civil control over armed force,2 and that all regimes resort for that purpose to means which may differ in detail and implementation but not in principle. All aim to stop those entrusted with the task of defending, or promoting the interests of, the sovereign community through force of arms from turning against it and coercing it into submission instead of serving it loyally by obeying its legitimate masters. As a result, any examination of the armory of civilian control in democracies is bound to start with classical methods of universal validity before it can concentrate on the differences in manner which separate them from less liberal regimes.

This, however, can no longer be the whole picture. Restriction of the civil-military problématique to issues of subordination and control was typical of periods or countries in which armed forces were simpler, hence more transparent to external controllers; freer in action, i.e., less dependent upon the parent society’s material and symbolic support; and, given the slowness of communications, more difficult to supervise from a distance. Such periods have long since gone by, and in only precious few countries do such primitive conditions still apply today. All through the twentieth century, security imperatives, the very size of armed forces, the amount of technology they utilize, the potential demographic, economic, social and environmental consequences of their action, have all bestowed on them a more central and permanent place in modern society, as well as transformed them into complex organizations that are more opaque to outside controls, and more sensitive to public opinion when it comes to recruiting, budgeting, internal norms and dynamics, or even missions. Conversely, increasingly rapid communications have lessened or removed the need for a priori methods of distant control.

Complexity, dependence, legitimacy constraints and easier communications go far to explain how, beside the traditional issue of Subordination which remains fundamental, another problem has emerged: that of coordinating military power and the various facets of civilian power within the state apparatus, as well as of mobilizing popular energies and backing in support of sovereign action. The problem is then less to restrict military autonomy or avert military coups—a pathology which now rarely affects the more complex societies—than to determine the proper amount of power and influence which should be accruing to the military establishment if it is to discharge its function without distorting the regime it is supposed to serve. In other words, the question resides in the type of principles which should govern the relationship between the military specialist and the statesman, by nature a generalist,3 and in the mechanisms most likely to optimize the balance between functional imperative—military effectiveness—and sociopolitical imperative: the harmonious integration of the military into society and state, which (in combination with perceptions of external threats) conditions its legitimacy. There again, the issue by far exceeds the bounds of liberal democracies. It is raised in broadly similar terms in most complex societies. But democracy clearly places special demands, which shall be underlined in due course, on civil-military systems. The following will be predicated on the thesis that democratic solutions to the problem as posed in contemporary societies are not fixed once and for all, give or take differences in manner, as when it comes to controlling the armed forces, but that the underpinnings of an ideal balance change over time as a function of trends affecting both external and internal contexts.

In brief, this paper’s main line of argument will move from a review of the classical methods of civil control to an examination of factors in modern civil-military coordination. The treatment will essentially be normative, even though history—in ideal-typical form—will be used: during the course of the last century the same values and imperatives have led to different outcomes according to the state of society and international relations. In the interests of conciseness and economy, it will leave out caesarism, praetorianism, garrison states and military-industrial complexes, i.e., the various pathologies, ancient or contemporary, of civil-military relations, the circumstances which are apt to generate them, the consequences they entail. The reference here will be to an ideal, stable, functioning democracy, deeply-rooted in political culture and institutions.

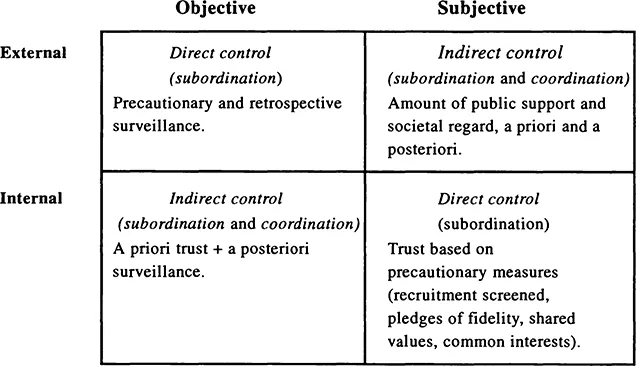

Figure 1.1 Controls Over the Military

Classical Methods of Civil Control Over Armed Forces

Principles of Direct Control

To secure the loyalty and subordination of soldiers (in the broader sense), all political regimes traditionally resort to an array of direct methods comprising objective/external and subjective/internal means. The latter, by nature precautionary, depend on screening personnel and manipulating symbols so as to maximize the likelihood of obedience and trust; the former, applied either a priori (precautionary measures) or a posteriori (retrospective), rely on institutional coercion, the power to allocate resources, and the utilization of divisions and balance-of-power relationships among the various components of the state security apparatus. Adding indirect methods (objective/internal and subjective/external: to be introduced later), the following 2x2 table, shown in Figure 1.1, summarizes the goals and principles of such controls:

Thus, the constitutional clause which makes the sovereign (in title or actuality) commander in chief of the armed forces, control of budget resources, periodic rotation of units (and prohibition of unauthorized movements: “cantonnement géographique”), the restriction of military personnel’s civil liberties and rights (association, speech, vote, eligibility, strike: “cantonnement juridique”), the functional separation of military from police forces, or that other application of the divide et impera principle which consists in encouraging inter-service rivalries, the promise of severe punitive sanctions for violating institutional restraints, temporary or permanent watchdog committees, all comprise the most frequent basis on which external objective political control rests.

It is usually supplemented in standing forces by administrative controls, directed at the middle and lower levels, less easily supervised than the upper echelons. Such controls normally include the power of evaluation and sanction of individual performance, unambiguous command chains clearly establishing responsibilities at all levels, and a coherent body of regulations prescribing sterner discipline and stronger commitment to organizational goals than are usually to be found outside the services. Finally, judicial control of offenses against the law of the land rounds out the system of restraints imposed on soldiers. This last type is generally weaker than the previous two in that civilian judges often lack the resources necessary to enforce their rulings upon the military, and their jurisdiction not infrequently stops at the threshold of a specific body of martial law enforced by military courts.

Subjective/internal control, on the other hand, consists in reserving access to the instruments of legitimate organized violence for those in whom the regime feels trust is not misplaced. When it comes to military leadership positions at the top, the power of appointment and dismissal is generally sufficient. The problem raised in that regard by mid-ranking personnel and the rank and file is more complex, since their loyalty cannot be verified on a personal basis. Temptation is therefore strong, especially if manpower requirements are low, to bar from the military those who are deemed potentially disloyal. To prevent the military establishment from becoming a state within a state, exhibiting ideals at variance with dominant civilian attitudes or pursuing sectional interests in conflict with perceptions of the common weal, governments can fill the ranks with citizen-soldiers, in the form of either conscripts or short-term volunteers. Less likely to develop a separate ethos than their long-career superiors, such citizen-soldiers act as a potential guard, in time of crisis, against any seditious intent or behavior on the part of their military leaders. Selective promotion can be used to the same effect among cadres. In more normal times, or when force level requirements are high, simple emphasis on patriotic socialization, stressing central sociopolitical values and loyalty to existing institutions (sovereign, constitution, nation, official ideology, often in the guise of an oath of allegiance) is usually enough. Should patriotism be weak or suspect (as was the case in West Germany after World War II), civic and political indoctrination, as well as machinery to weed out unsavory orientations, are resorted to. Finally, compensation for the real or potential hardships and constraints of military life (risk to life and limb, open-ended terms of service, formal and informal demands placed on individuals), when it takes the form of substantial material or symbolic privileges, adds self-interest to the reasons soldiers have to remain loyal to their political masters.

Such practices are so basic and habitual as to become almost invisible. They nonetheless remain in force in the constitutions, laws, regulations, organizational cultures and personnel management norms of most states, and continue to shape behavior and attitudes.

Democratic Norms of Civil Control

Having recognized that democracies face the same fundamental civil-military problems as other, less liberal regimes of the past or present, and that some of the solutions to which they have recourse do not differ greatly in principle from those used under non-democratic conditions, the next question is what distinguishes them from absolute monarchies, dictatorships or totalitarian states.

The most obvious answer is that liberal democracy is a form of government based on popular consent and political compromise. Executive and legislative holders of sovereign power are directly or indirectly elected by the people, and subject, like all citizens, to the rule of law. The arbitrariness inherent in any exercise of power thus finds itself formally limited. It follows that where dictatorial and totalitarian regimes rely on personal (often charismatic) ties, political discrimination, secrecy, brute power relationships, police surveillance or even terror, democracies allow persuasion through values or self-interest, the authority of impersonal rules, and public opinion pressures to play a prominent role in civil-military relations. Democratic control of military behavior is less abrupt, and less dangerous for those concerned, since beyond the special demands imposed on them by their legal status, their rights as citizens are formally guaranteed. The subjective/external form of indirect control through the amount of public support and social honor enjoyed by the military, though present and (in some circumstances, not least war) critical under any regime, figures prominently in democracies since public opinion is more central to the way political games are played in them, and status differentials cannot be imposed from above.

The second major difference is that while totalitarianism equates loyalty with ideological conformity (if not positive fervor and zeal), and dictatorships insist on active political allegiance, democracies only imply partisan neutrality on the part of uniformed personnel, at least when acting in an official capacity. The need for such apolitical, nonpartisan behavior, without which democratic political pluralism would soon be impaired, accounts for the restrictions, of varying scope according to time and place, applied to soldiers’ civil liberties. Yet, this principle finds its limits in the no less necessary adherence to the tenet of political pluralism itself, for the risk exists (as was observed time and again in the West during parts of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries) that military professionals may construe partisan neutrality less as remaining outside than as standing above politics. The latter conception, with its implicit assumption of a supra-constitutional status for the military (“governments, regimes pass, the armed forces remain”), betrays lack of respect for that central character of democratic life: the elected representative of the people, and may lead the top military leadership to picture itself as arbitrator or last recourse, thereby sanctioning the ruin of democratic principles.4

This brings us to a third difference. There are more natural tensions, both structural and ideological, between a democratically organized society and its military institutions than between the latter and illiberal regimes. Civilian pluralism contrasts with centralized military command; middle-class predominance, with the quasi-aristocratic status of officer corps within the social structure of armed forces; civilian values—freedom, equality, prosperity—with values such as authority, cohesion, discipline and honor, which derive naturally from the performance of truly military (i.e., combat) roles. The democratic need for openness and freedom of information contrasts sharply with the military necessity for (or, as the case may be, infatuation with) secrecy. The list of such contrasts could be lengthened at will.

The various manners in which these tensions are resolved characterize each polity and period: more on that later. But success in resolving them requires legitimacy and stability, hence strong institutions. Democracies, while on the face of it more vulnerable than less delicate regimes, have historically proved more resilient than them if the long view is taken.5 It is so despite the fact that they are less able to control the factors which govern the military’s informal influence upon society. But no doubt, the absence of aggressive militarism normally (though not always actually) associated with democracy contributes to stability, just as—all things equal—prosperity and the protection of individual rights serve to foster democratic loyalties among military and civilian alike.

If indeed one regards military coups as the most serious setback civil control may suffer, and if one takes seriously the conclusion reached by political scientists after decades of comparative studies—to wit, that it is not so much force of arms as power vacuums which generate military intervention in politics6—, then the fact that contemporary democracies are spared that phenomenon seems to confirm their superiority. While totalitarian regimes proved capable of firmly controlling their militaries, they did so at prohibitive costs which led to their ruin: internal coercion, external aggression, and eventual exhaustion of social energies through war or economic ineffectiveness.

The Diversity of Democratic Political Institutions and its Impact on Civil Control

It should be noted, however, that democratic institutions are diverse, and not equally conducive to effective civilian control, notably of the external/objective variety. Some make it easier, others more problematic. Thus, political systems based on a structural division of sovereignty, such as a strict separation of executive and legislative powers, or federalism, experience a major hindrance to the subordination of the military.7 One can easily see why: in such systems, military elites can always play...