![]()

Part I

Framing the discourse of Vertical Urbanism

![]()

1

Vertical Urbanism

Re-conceptualizing the compact city

Zhongjie Lin

Although the term “compact city” appears frequently in academic accounts of sustainable urbanism as well as in professional documents for planning projects, it is often used in a manner generally linked to certain well-established principles including high density, mixed uses, walkability, and transit-oriented development (TOD). The fixed language ties the concept to traditional Western urbanism, while the compact city actually possesses the power to generate dynamic urban forms, utilize cutting-edge technologies, address pressing environmental issues, and respond to distinctive geographical and cultural contexts – thus enabling it to challenge conventional notions of urbanism. The awareness of limitations of current theory and practice leads to the introduction of Vertical Urbanism as an alternative discourse of the compact city responding proactively to the state of contemporary metropolises characterized by density, complexity, and verticality. Vertical Urbanism distinguishes itself from the nostalgic idea of neo-traditional urbanism on the one hand and the static Modernist notion promoting tall buildings as dominant urban typology on the other. In contrast, it advocates physically interactive and socially engaged forms addressing the city as a multilayered and multidimensioned organism.

We have been investigating the concept of Vertical Urbanism and studying its influence in urban design through a series of capstone studios in the Master of Urban Design program of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. These studios, conducted in several cities in the United States and China, focused on various design issues such as urban infrastructure, transit system, industrial waterfront redevelopment, and downtown revitalization, and tested the concept in different geographic and cultural settings. This chapter will first trace the historical development of and debates surrounding the concept of the compact city, and define the approach of Vertical Urbanism from both historical and practical dimensions. It will then examine important urban design issues based on Vertical Urbanism through the studio projects, including the relationship between density and vitality, the relationship between horizontal and vertical dimensions, space of flow and scalar shift, as well as the ecological and social adaptability of mega-forms. These pedagogical experiments helped frame the design methodology of Vertical Urbanism, and explore the capacity of this global urban paradigm to provide localized design solutions.

Debates on the compact city

The compact city is a relatively recent concept in the discourses of urbanism. Many attribute the idea to Jane Jacobs and her seminal work The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which argues for dense and diverse urban centers like Manhattan over the planned Modernist City or Garden City; but it was not until the late 1980s that the term “compact city” became commonly used academically and professionally.1 Studies of the compact city have evolved along with rising awareness of climate change and the global movement of sustainable development following the 1987 Brundtland Report.2 This report, published by the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development, prompts policy makers as well as professionals to rethink the role of urban design and development to better protect and sustain human habitats. As a result, the idea of the compact city was circulated in both policy circles as well as professional planning and development communities, and became particularly influential in Europe, where political leaders and the general public appeared to be more concerned about issues pertaining to energy shortages, global warming, and negative impacts of urban sprawl.

Two documents, both published by European governmental agencies in 1990, are instrumental in this endeavor. One is the United Kingdom’s White Paper on the Environment, also published as This Common Inheritance.3 The other is the Green Paper on the Urban Environment, published by the Commission of the European Communities.4 Both recognize the role of urban planning and urban form in achieving environmental and urban sustainability, and advocate the compact city as a solution of the dilemmas facing European cities.5 The Green Paper particularly favors the planning approach of the compact city, not only for its environmental benefits including energy consumption and emissions but also its potential contribution to the quality of life. Both documents have been quite influential and led to a series of other publications which further articulate this concept. One of these well-known books is titled Towards an Urban Renaissance, written by the Urban Task Force led by Sir Richard Rogers in the United Kingdom in 1999.6 These documents characterize the compact city as a form of high-density development with increased socioeconomic diversity and an improved public realm encouraging low-carbon lifestyles and supported by public transit infrastructure. Influenced by these discourses, the compact city has grown into an important component in the practice of sustainable urbanism, in fighting urban sprawl, and in linking attributes of physical urban form to a healthy environment and society.

However, there have been different definitions of the compact city and opinions regarding its impact on city building. Michael Breheny’s essay “The Contradictions of the Compact City,” published in 1992, summarizes the early – and still unresolved – debates on the concept and its planning implications.7 On the one hand, its proponents claim that the compact and functionally mixed urban form can meet two major planning objectives neatly: to protect the natural environment and to foster the quality of life in a healthy city. On the other hand, opponents point out several limitations of the concept. Critics suspect that the relationship between a compact urban form and environmental improvement might not be as direct as its sponsors claim. They also criticize that the prevailing definitions of compact city are tied primarily to Western models, often referring to premodern or early modern urban forms in Europe, and thus represent a particular set of fixed cultural identities.8 Although most scholars recognize that a compact form contributes positively to urban sustainability, the criticisms nevertheless indicate inadequacies of current approaches to building a compact city.

Since the 1980s, New Urbanism has gradually developed into a dominant discourse of city building in the United States, in concurrence with the growth of the organizations supporting it, and it has influenced urban design practices across the world. Proposals for designing compact cities are often associated with principles of the New Urbanism movement like high density, mixed-use, walkability, traditional neighborhood development, and transit-oriented development (TOD). While these principles represent fundamentals of sustainable development, the fixed design language further strengthens the compact city’s connotation of traditional Western urban form. In addition, complex political, social, and cultural factors in contemporary societies have led to different forms of urban density, and demand incorporation of regional contexts both morphologically and sociologically in urban design practice. The expanding territory of human agglomeration has also led to a growing scale of urban systems, including its mass transportation, information networks, and ecological systems, which in turn are changing the process of urban intensification. These global conditions, thus, require a reinterpretation of compactness in which a higher degree of integration and interaction of urban components becomes the key.

Concept of Vertical Urbanism

The Master of Urban Design program at UNC Charlotte has been engaged in the investigation of Vertical Urbanism as an alternative approach to the design of the compact city. This concept responds proactively to the state of contemporary metropolises characterized by the relationships of density, complexity, and verticality. It is concerned with physically complex and socially engaged spatial forms featuring the contemporary city as a multilayered and multidimensioned organism. Vertical Urbanism thus distinguishes itself from the nostalgic idea of New Urbanism on the one hand and Modernist notions promoting tall buildings as a dominant urban typology on the other. We have continued to frame the methodology of Vertical Urbanism in the context of a series of capstone urban design studios, using them as laboratories to investigate the design, ecological, and sociocultural dimensions of building the compact city.

Vertical Urbanism particularly addresses design issues of high-density urban areas supported by complex urban systems that conventional planning approaches are only able to manage with limited success. When urban density reaches a certain point, verticality becomes a crucial attribute of the city. In such a city, all components of urban design including circulation, land uses, open spaces, ecologies, and human activities are distributed in a different pattern and their relationships mutate. As we can see in some of the world’s megacities like Hong Kong, Shanghai, Tokyo, Seoul, and New York, the floor area to plot ratios in some areas go beyond 1:12 and residential densities exceed 400 persons per acre. With such intensity, the planning area of a city is no longer its surface but the entire built-up zone and the potential buildable vertical space above and beneath. In such cities, transportation, programs, and open spaces are highly integrated in a system that stretches from underground to the tops of buildings. Given such complexity, we can no longer simply focus on the site plan and layout of buildings, but should examine the city as a three-dimensional matrix for urban design solutions.

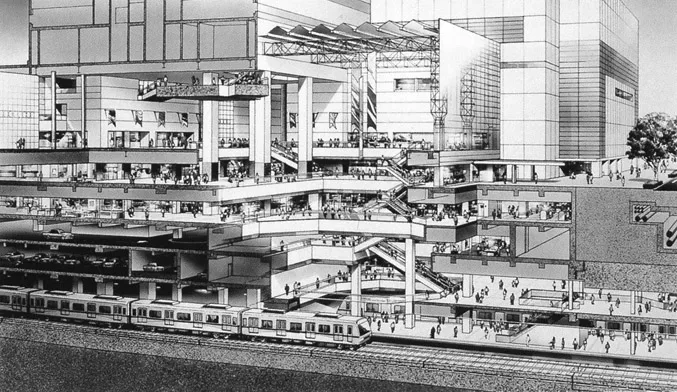

Figure 1.1 Yokohama Minato Mirai 21 Central Station

Studying urban verticality not only deals with the spaces above the ground; it involves looking beneath the land to examine underground transportation, service, and uses, as well as their relationships to the uses and structures above. The designs of urban areas surrounding major train stations or metro interchange stations in such cities as Tokyo and Shanghai represent some best examples for such vertical spatiality through height as well as depth. The multilevel underground spaces often link commercial developments, public uses, pedestrian circulation, and parking facilities to an inner-city or inter-city transportation node, all of which further connect to the public areas and open spaces above. The complexity of different systems involved in the planning of such a multimodal transportation district entails systems design thinking and an integrated planning approach.

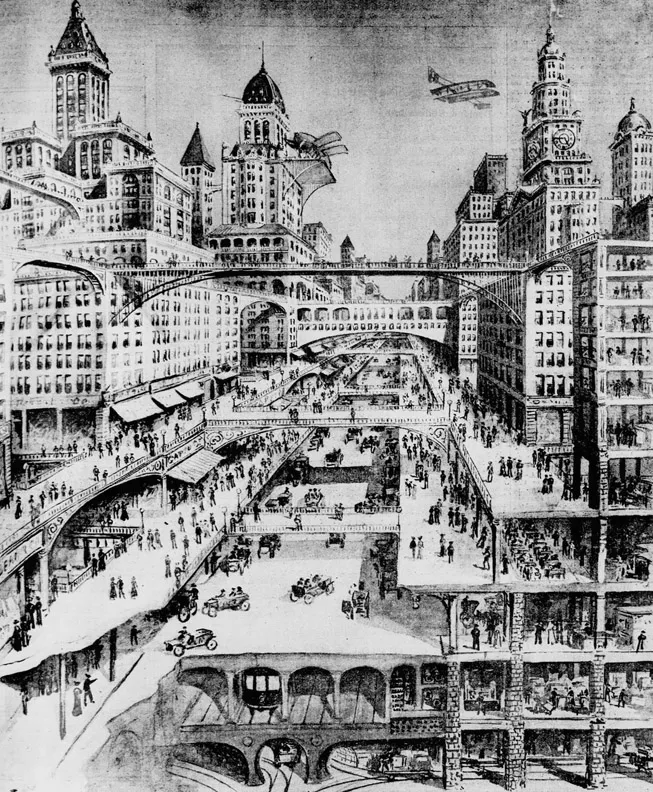

Although Vertical Urbanism is not a brand-new idea, its concept and methodology are yet to be critically articulated. Architects and planners have long dreamed of urban forms to address the growing density of cities for a century or more. The illustrations of a future New York drawn by Richard Rummell and other artists in the 1900s and 1910s envisaged vertical cities consisting of skyscrapers linked together by interconnected bridges and serviced by automobile and rail transportation networks on different levels above- and underground.9 Although these early twentieth-century visions of the city as a machine have fallen out of favor, the question remains relevant: can we design an urban environment of high intensity that is efficient, sustainable, and livable, with the amenities, landscapes, and lifestyle choices that we enjoy on the ground? Such imperative has continued to grow as cities have become ever larger and urban systems more sophisticated, and contemporary technologies are offering more options to realize such an urban form.

Figure 1.2 King’s view of New York, by Richard Rummell, published by Moses King, 1911

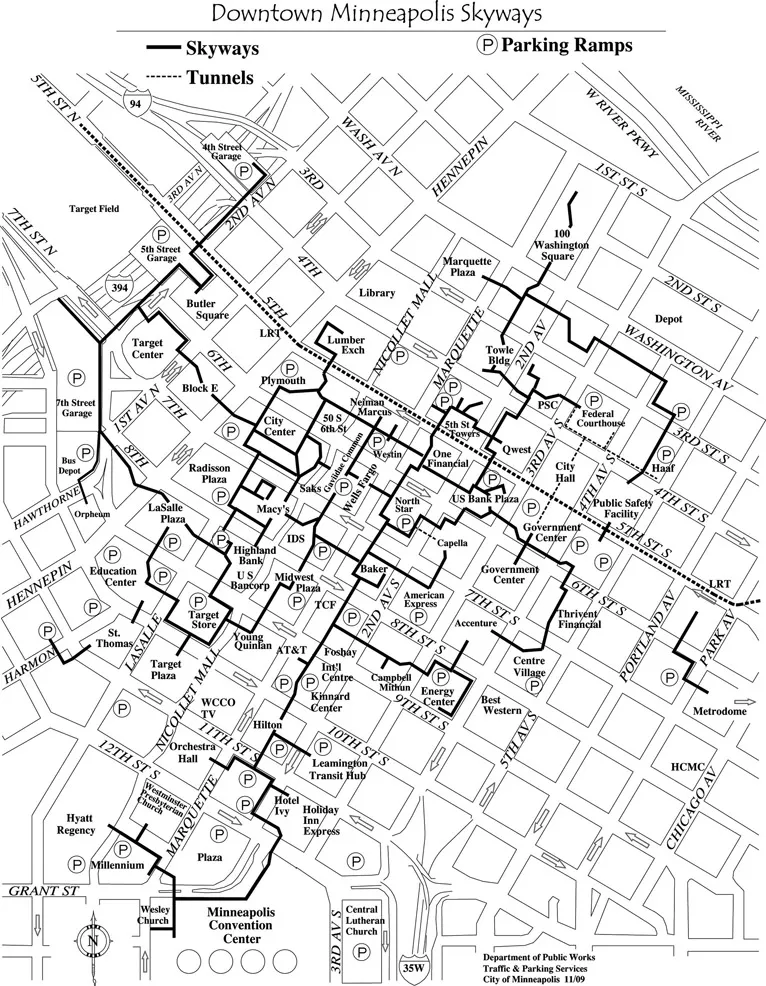

Figure 1.3 Map of downtown Minneapolis skyways

Figure 1.4 “City in the Air,” by Arata Isozaki, 1960

The mid-twentieth century witnessed many attempts in practice – both pragmatic urban tactics and ambitious utopian schemes – to conceptualize such verticality in urban design. The skyway system in downtown Minneapolis, inaugurated in the 1960s, was one of such meaningful experiments, although it focused primarily on the system of pedestrian cir...