![]()

1 The Thai economy in the early years

1961–1990

1. Introduction

The bad experience of hyperinflation after World War II shaped macroeconomic policy in Thailand in the early 1960s. The fear of hyperinflation raised inflation awareness, which led to conservative fiscal and monetary policy. Price stability was given top priority more than other macro policy goals. It had strong implications on the conduct of fiscal and exchange rate policy in subsequent decades. As an introductory chapter, we discuss causes and remedies of hyperinflation by referring to Thailand’s evolution of the banking and trade sectors. Then we move on to discuss the Thailand’s macroeconomy during the first three decades of economic development from 1961 to 1990. We will understand how the development of the banking sector helped reduce the pressure on the price level. Nevertheless, expansion of international trade brought along inflationary pressure via rising prices of traded commodities. We will also examine the role of fiscal policy and exchange rate regimes, which are related to a mechanism which tends to correct internal and external imbalances. We can characterize this early period of Thailand’s development as a period of strong growth with price stability. However, impressive GDP growth can be misleading unless we take into account of macroeconomic imbalances. Actual GDP growth must be adjusted downward by a certain degree of external and internal imbalances.

2. Hyperinflation and the return to price stability: 1948–1960

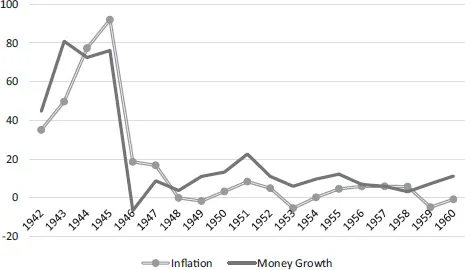

For money to perform its role as a medium of exchange and a store of value, the price level must be stable to create public confidence in the value of money they are holding. During World War II, huge spending of the Japanese military force in Thailand was financed by printing money. The rapidly growing money supply led to hyperinflation which peaked in 1945 at 92 percent, while money supply expanded at 76 percent (Figure 1.1). This was the only time when Thailand experienced hyperinflation.

After the war, excessive growth in money supply and the resulting hyperinflation was curbed by issuance of long-term government bonds. As a result, a negative growth of money supply was observed in 1946 together with a plunge in inflation rate (Figure 1.1). This was the result of issuing long-term government bonds to mop up excess money supply. Controlling the money supply is necessary to curb hyperinflation. However, inflation would have not come down unless there was also declining inflationary expectations. The hyperinflation in Thailand was high but not as high as those hyperinflations in Germany during 1920–1923, Zimbabwe in 2011, or Venezuela in 2018. Coomer and Gstraunthaler (2011) attributed reckless spending and exploding budget deficits to hyperinflation in Zimbabwe. Also, the forced seizure of commercial farms almost brought agricultural production to a halt. Zimbabwe’s state of hyperinflation culminated into dollarization.

Figure 1.1 Hyperinflation and growth rate of money supply

After price stability had been maintained in Thailand in 1948, confidence in the baht was regained. The national currency resumed its role of the medium of exchange and the store of value; commercial banks were able to attract deposits and perform the role of financial intermediaries.

Branches of foreign banks operating in Thailand during this period mainly conducted business related to international trade. Domestic commercial banks did not actively engage in mobilizing savings because the ability of savers was constrained by low income in the aftermath of the war. Commercial banks engaged mainly in financing foreign trade transactions. In 1945, there were only 11 branches of commercial banks. When international trade expanded, it required more banking services and more branches of commercial banks. By 1954, the number of bank branches for the whole country increased to 72. Nevertheless, these branches were not able to attract savings because banking habits among the Thais had not firmly rooted. Saving was carried out by gold hoarding, because gold was considered a liquid asset and status symbol. As a result, savings and time deposits amounted to only 1 percent of GDP in the period of 1948–1960.

Commercial banks had no incentive to mobilize savings since loan demand was low. Limited investment opportunity did not generate high enough demand for loans to urge banks to mobilize savings. Bank credit amounted to 2 percent of GDP. Moreover, banks were not interested in holding low-yield government bonds. The lack of banks’ lending and investment in assets was reflected in a high level of idle cash balances held by banks. According to Yang (1957), the average cash to bank deposits between 1947 and 1954 was around 34.5 percent. Nevertheless, bank excess reserves declined as the economy recovered from recession. Economic recovery in the early 1960s generated higher demand for bank loans and banks were able to reduce their idle cash balances.

Because of subdued inflation, the internal value of the baht was maintained steadily after the war, but the external value of the baht was unstable prior to 1955. The shortage of foreign exchanges led the government to adopt a multiple exchange rate system, in which exporters and importers were subjected to different exchange rates. The exchange rates for essential export commodities such as rice, rubber, and tin were undervalued to discourage exportation, while the exchange rates for imported goods were set closer to the free market rate. The motivation for the multiple exchange rate system was to prevent shortages of essential commodities. The success of the system was the ability to control inflationary expectations. There were some costs associated in terms of inefficiencies arising from disported commodity prices. Black markets and smuggling activities, and disincentives for producers of essential commodities, were natural outcomes of the multiple exchange rates. Once the inflation rate declined, as inflationary expectations died off slowly, there was no need to maintain this distorted exchange rate system.

As a result of the unification of multiple exchange rates into a single exchange rate since 1955, the baht exchange rate remained stable throughout the period 1955–1960. Speculations in foreign exchange markets were eliminated. The stable monetary environment in the late 1950s provided a necessary condition for a stable demand for money corresponding to expanding economic activities.

Investment opportunity and liquidity were improved for commercial banks during the period 1955–1960. New branches of commercial banks were established at the annual rate of 18.5 percent. Between 1955 and 1960, the ratio of time and savings deposits to GDP gradually increased to 3 percent on the average. At the end of 1960, the number of bank branches increased to 324 branches for the whole country. The increasing number of bank branches provided opportunities for financial savings that would otherwise had been put into physical assets or non-productive assets. Since both the ability to save and the opportunity to save were enhanced through rising income and bank branches, the only remaining factor for successful financial deepening was the willingness to save, which depends on positive real interest rates.

The interest rate on government bonds was raised from 6 percent to 8 percent in 1956. Trescott (1971) pointed out that this change led to a great increase in holding of government bonds by banks. Consequently, the government’s reliance on credit extended by the Bank of Thailand was reduced. When commercial banks bought bonds to finance budget deficit, the process did not involve increasing the level of high power money. The implication is that government budget deficit can be financed by non-inflationary means.

3. Stable growth path: 1961–1990

The year 1961 was the year in which the first economic development plan was implemented. The focus was on building basic infrastructure. The share of investment to GDP rose from 15 percent to 25 percent in 1968, while the average annual GDP growth rate was 8.1 percent. Despite the high GDP growth, the average annual inflation rate was 2.2 percent. Low inflation and strong growth of per capita income led to substantial increases in deposits in commercial banks. The low inflation rate during this period means that the real rate of return from bank deposits was positive, providing incentive for financial saving. To promote saving, interest earned from saving and time deposits were tax exempted, raising the real net return on bank deposits further. Bank deposits became very attractive long-term financial savings.1

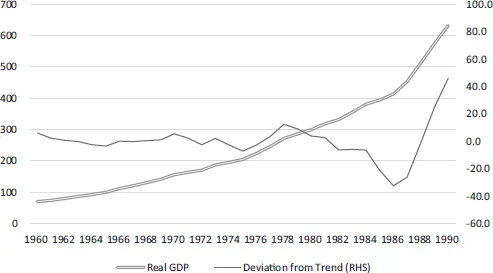

From 1961 to 1990, real output increased more or less at its trend growth path of 7 percent.2 There were some episodes that actual GDP was above the trend, as new growth engines emerged. On the other hand, actual GDP fell below the trend because of the two oil price shocks during the period 1973–1974 and the period 1979–1980 (Figure 1.2). The slowdown in exports in the early 1980s as the result of the real exchange rate appreciation caused the output to drop below its potential level. The 1984 devaluation restored international competitiveness and the economy was spurred by rising export demand once again. The Thai economy regained the pre-shock growth path rapidly after 1986.

Figure 1.2 Stable growth path: 1960–1990

Policy responses to external shocks such as oil price shocks have significantly influenced the rate of economic growth in developing countries (Balassa, 1985). Thailand engaged in an outward-oriented policy stance at the early 1970s through heavy reliance on export promotion in response to external shocks. The trade policy had favorably affected growth performance. There was a positive deviation of output above its trend from 1988 to 1990.

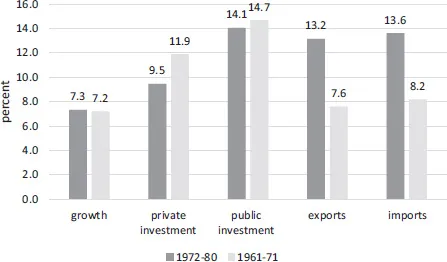

Figure 1.3 illustrates that growth was driven by investment, exports, and imports. Although imports rose sharply during the oil shocks, both investment and imports were highly correlated. A large part of imports was capital goods. Imported capital goods contributed to productivity improvement in the manufacturing sector, which in turn gave rise to competitiveness and enhanced export capacity.

Comparing the periods 1961–1971 and 1972–1980, the average growth rate between the two periods was almost identical at around 7.2 percent. In the second period, the shock was more severe due to the sharp decline in the terms of trade. The reason why GDP growth was maintained at a high level is the rapid growth of exports. Exports grew every year from 7.6 percent in the first period (1961–1971) to 13.2 percent in the second period (1972–1980). Figure 1.3 shows that other engines of growth, private and public investment, grew less rapidly in the second period.

In the early 1960s, the first economic development plan was launched. As early as the 1960s, important economic institutions were established: the Board of Investment, the National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB), the Bureau of the Budget, and the Fiscal Policy Office. Development strategy adopted import substitution policy. This was the period of establishment of quality institutions, which matters for the long-term growth of the economy. The economy was able to grow rapidly without succumbing to high inflation, while maintaining external equilibrium. In the first development plan (1961–1966) the emphasis was given to infrastructure investment and the promotion of private investment. On the average in the period 1961–1971, public investment and private investment grew by 14.7 percent and 14.1 percent, respectively. Growth was driven by exports and investment during this first period.

Figure 1.3 Growth of aggregate demand components

In the second development plan (1967–1971), import substitution was replaced by export promotion policy; its impact was not obvious until after 1970, when the share of exports in GDP began to rise rapidly, reaching 35 percent by 1990 (Figure 1.4). The rising shares in GDP of exports and investment implies that, for a given level of export and investment growth, the impacts on output growth of increases in investment and exports had become larger.

Balassa (1978) provided the evidence supporting the hypothesis that exports, in particular manufactured exports, are related to economic growth. Exports permit the exporting countries t...