![]()

1

A background to school planning and design in Africa

Introduction

This chapter sets the background to this book by giving a brief account of the evolution of Western education in Africa and its influence on school design. It focuses mainly on its development in English speaking, former British colonies in West and Southern Africa. Drawing from research sources, it traces the involvement of Africans in Western education, from the children of the elite coastal traders to the mass education movements in the mid-20th century. Giving examples from schools in Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa, it contextualises and compares the evolution process which took place across key Anglophone countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Introduction – early schools in Africa: pre-Western education systems in Africa

Historically, Africa has often been portrayed in the public media and the local imagination as being the dark continent in which there has only been a limited and recent spread of formal Western education.1 Factually, the continent has had a long and engaging encounter with European or Western education systems that now stretches back more than two centuries.2 Prior to the transatlantic trade, traders from Europe were involved in commercial activities with indigenous coastal groups who engaged with the European merchants and developed trading systems for the transactions that took place. Whilst in these early days there was no established school system, often children of African traders and kings were sent to Europe for a proper ‘Western’ education.3

This is not to say that there were not historic indigenous education practices, usually associated with initiation rituals, that existed and still do so in different regions in Africa. The ‘fattening’ house system, for example, remains a traditional practice amongst the Efiks in southeastern Nigeria. The practice involves the sequestering of pubescent girls to a private dwelling and living area, where they are schooled in the arts of cookery and other domestic affairs for a month, whilst fed food to ‘fatten’ them. At graduation from the school, or fattening house, the graduates are presented as brides to men in the local community. Similar education ritual practices take place

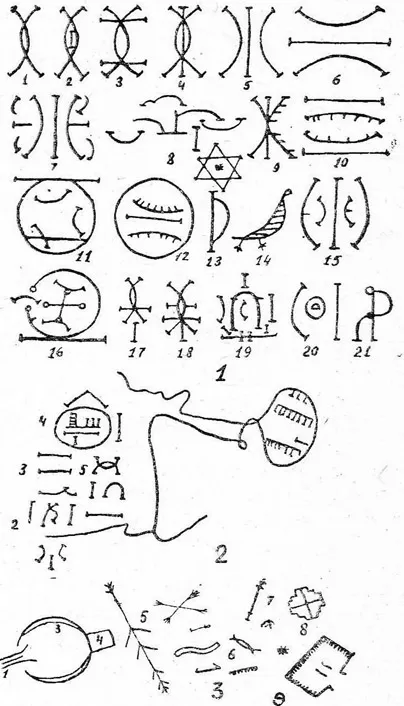

Figure 1.1 Nsibidi – Southeastern Nigeria Secret Society Script

amongst southern African groups such as the Xhosa and the Zulu have initiation rituals for males coming of age which again involves the youths being removed from their local village settings and taught the ‘ways of manhood’ over a period before being circumcised and then being reintroduced into their society as men.4

Also of note were the initiation and membership activities of traditional secret societies in Africa. In southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon, the nsibidi script was created by the Ekpe or Leopard Society; where teaching of the character script and other society rules would take place at the shrines or meeting places of these societies (see figure 1.1). This has been taken to the New World and has links to the Abakua Society in Cuba, who continue with this tradition, calling the writing system anaforuwana.5 Again in these cases, a specific and designated space for the instruction and preparations of the initiates beforehand for these ceremonies would be constructed, albeit of an only temporary status.

Figure 1.2 Islamic School, Northern Nigeria

The arrival of Islam from the 7th century affected education provision in North African or the ‘Maghreb’ countries,6 the regions to the northernmost parts of West Africa,7 and parts of East Africa facing the Indian Ocean seaboard.8 In these regions the historic madrasa school system been established and retained popular prominence even with the advent of Christianity and the missionary based education systems (see figure 1.2). The madrasaschool currently remains in place in most of the described Islamic regions of Africa. It is usually designed and built as an attachment to existing local mosques and has the primary function to provide Koranic learning to boys, overseen by local Islamic teachers or imams.9 On occasion the madrasas are established structures, built separately from the main mosque, and do have architectural merit in their own right.

Africa did have a number of institutions such as these described that provided a form of pedagogy and instruction within societal groups. Many of these pre-Western education institutions have survived to the present day often taking place in parallel to the now official ‘Western’ education school systems. Their centrality to the educational experience has changed; traditional initiation ceremonies now take place at weekends or during school holidays. In many countries such as Nigeria and Ghana, most madrasa schools have been incorporated into Western education programmes in collaboration with local Islamic teachers.10 In other states, madrasas now run as evening or weekend classes for pupils who attend Western-style schools during the week. Thus, the significance of these pre-Western educational systems has diminished in socio-cultural importance. This is in contrast to the critical importance now afforded to the acquisition of Western-style education. For most African societies, this is linked to the understanding that Western education is now crucial for progress in all forms – social, economic and cultural – at both individual and community level in contemporary Africa.

The continued persistence of these historic or traditional knowledge practices for religious and cultural reasons, however, demonstrates that societies are often able to negotiate their engagement with traditional and modern systems – in this case, knowledge acquisition – that enables access to future development and the modern world (through Western education) and a stake in historical-religious cultural practices (through initiation ceremonies and madrasa schools), which forms their continuing link with important traditional systems.11

The arrival of the missions

By the mid-19th century, only a small proportion of the African elite were able to send their children abroad to acquire a Western education, or had the wherewithal to employ private tutors. For most Africans, this period saw the introduction of formal Western education through the activities of the plethora of missionary groups and societies involved in bringing Christianity to Africa. A number of authors have written definitive texts on the early Christian missions in Africa. There are also first-hand archival accounts of the establishment and building of ‘missions’ written by these missionaries and their associates. In West Africa, the writings of the Presbyterian missionaries Mary Slessor and Hope Waddell give an insight into the challenges and successes of setting up these institutions.12 In Southern Africa, similar memoirs exist in relation to the setup of Lovedale, in the Eastern Cape, South Africa, the Buxton School at Frere Town and Rabbai near Mombasa, East Africa and elsewhere.13

The development and design of mission schools in Africa was directly linked to missionary exploration and establishment on the continent. The ‘mission’ was often the same semantic term used for the church, school and dispensary, and as such was central to both proselytising and also community development in the town and villages in which they were situated.14 However, usually the location of the mission settlement was physically set apart from the local village homestead. In Eastern Nigeria, as Achebe narrates in his historic-fiction novel Things Fall Apart and corroborated in Waddell’s Presbyterian Mission Calabar diaries, the location of the mission settlement was physically set apart from the villagers’ dwellings, as there was significant local resistance to the new ‘missionary religion and its converts’.15

Missionary school design was thus initially an addition to the general construction related to missionary church infrastructure including missionary housing, dispensaries, small cabinetworks and the like in Africa. The first coastal missions had building materials transported from countries, such as the UK, in prefabricated forms and occasionally as ships’ ballast.16 Initially, classes were conducted by the missionary or catechist within the church until school premises could be built.17 In the case of the Methodist mission in Badagry, Nigeria, the first missionary school was a prefabricated house with the school master’s house above, as was the Hope Waddell (Presbyterian Mission) College in Calabar (see figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Hope Waddell College, Calabar, Nigeria

Away from the coast, the first mission schools were built using local materials comprising local earth wattle and daub for walls, and grass thatch for roofing. There are existing photographic records that document these schools.18 A significant school built of earth or ‘tubali ’ in the local Hausa language, in West Africa was Katsina College. This was in direct keeping with the local Islamic architectural style of the city and Hausa region in general (see figure 1.4).19 As local building materials, such as clay and structural stone, were discovered and building skills such as carpentry and brickmaking and laying were taught and developed, school buildings became constructed as more substantial infrastructure.

At their height, in the late 1940s to mid-1950s, missionary schools were well-run institutions that received grant aid funding from the colonial government’s education office and also denominational funding. This meant they had both well-paid teaching staff, and well-built and -maintained classrooms and other school infrastructure. Thus with the historically established early coastal missions and sources of government and missionary funding a network of schools – from small village schools to large, well-established secondary institutions and teaching colleges – emerged whose architecture and style, as well as academic results, were of equivalent status to the later government-funded colleges.20

Figure 1.4 Katsina College, Katsina, Nigeria

The string of Ghanaian coastal colleges including Adisadel (CMS) Mfantispim (Methodist) and St Augustine’s College (Roman Catholic) showcase the best of this legacy.21 A number of these missions also set up teacher training colleges, or seminaries in the case of the Catholics, which were generally at higher secondary level. Of note is Fourah Bay College, Freetown, Sierra Leone, which is the only African tertiary institution and has its origins from this Christian (CMS or Anglican) denominational legacy.22

The colonial schools

By the mid-19th century, much of Africa had been claimed by various European powers. The British controlled trading across a swath of Southern and East Africa and had protectorate territories in West Africa. There were further ambitions of explorer entrepreneurs such as Rhodes pursuing their aim to run a route from the South African Cape to Cairo in Egypt. After the historic 1884–1885 Berlin conference resulting in the carving up of Africa, the missionary impact in Africa was also to reach its height by the early 20th century with all major religious denominations having established mission stations across much of the continent. The early 20th century also say the setup of a colonial administrative apparatus that ensured that institutional infrastructure such as schools, clinics and administrative offices were built in all cities and towns across its African colonies.

This resulted in a network of (colonial) government primary and secondary schools that were built to augment the existing missionary school network, and indeed to bring Western education to Islamic areas in northern Nigeria, Ghana and also in East Africa in areas such as Mombasa and Zanzibar. Primary and secondary schools outside the major cities were generally basic affairs, built and designed to the colonial Public Works Department (PWD) specifications.

Thus from the early 20th century, African schools could be run and owned by religious missionary bodies such as the Catholic church, the Church Missionary Society (CMS) or the Methodist church, or by the colonial government. By the mid-20th century, some communities and towns in the southern parts of West Africa, home town associations were able to raise funds for the building of schools, and then to negotiate to hand over the running and administration of these institutions to religious groups.23 All forms of schools, whatever their ownership, were entitled to receive funding through the grants-in-aid system from the colonial government. This was subject to these schools meeting required standards in building and teaching, as well as attainment in examinations.

As a general rule, African cities and large towns such as Freetown Accra,...