![]()

1 ‘A scratch team with gentlemanly instincts’

The Corinthians and English soccer in the late nineteenth century

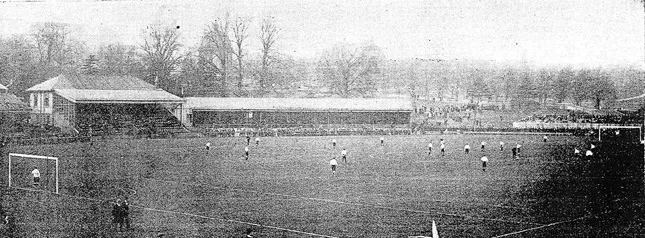

Figure 1.1 Crystal Palace, Sheriff of London Shield, Corinthians v Sheffield United, 19 March 1898.

From Sports (Illustrated), pub. Sheffield, 6 April 1898.

In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, where the lives of the great and the good are recorded, the headline descriptor for Nicholas Lane Jackson is simply ‘sports administrator’. As assiduous in promoting himself as the business ventures and sports activities in which he was involved, Jackson would not have been so modest. The autobiographical note with which he prefaced Always Fit and Well (1931), a volume offering advice on living to a ripe old age, left readers in no doubt as to his achievements over the course of a busy and successful career. He had ‘played nearly every English game with a certain amount of success’ and edited numerous magazines as well as handbooks on various sports, thus acquiring ‘an all-round knowledge possessed by few’. All this had been achieved without neglecting his many business interests.1 It helped, of course, that so much of Jackson’s business was sports-related, such as the affairs of the Corinthian Football Club, with which he was closely associated from 1882 to 1898, the first sixteen years of its history. What follows is an account of the club’s origins and progress set in the context of the modus vivendi between amateurism and professionalism that emerged in England after the mid-1880s. The spotlight is then turned on to ‘Jackson’s Corinthians’, as they were sometimes known, and the practicalities of running a successful amateur club from the early 1880s through to the turn of the century.

During his career, Jackson exhibited many of the qualities often attributed to entrepreneurs. He was an outsider, the son of a cheesemonger, who affected the gentility required to do business with the rich and famous; he was an opportunist who made connections between sports and sports-related activities to create new products; he was a publicist who recognized instinctively the value of a distinctive brand. Much of this was evident from the notice published in Football in October 1882, announcing the arrival of ‘A NEW ASSOCIATION CLUB’, open to ‘international and well-known players’, which would play on Wednesdays. Should anyone doubt the club’s credentials, there was ‘some probability that it would amalgamate with the old Wanderers’ – they had won the English Cup five times in the 1870s – ‘and if so a club historical in football annals will be revived’. Jackson, honorary secretary of the London Football Association (LFA), would arrange fixtures, ‘some of which will be with strong provincial clubs’.2 It is possible to discern here the essence of the project that was eventually to unfold. What was being proposed was an elite club for soccer players of social standing and exceptional ability. Playing on Wednesdays indicated that it would be open only to those untroubled by the constraints that kept most young men at work mid-week. Finally, the prospect of matches with clubs from outside London was intriguing, especially when it was announced later that tours would be arranged two or three times a season.3

At the time, Jackson was also the assistant secretary of the Football Association (FA), the English game’s governing body. Later, when explaining his motives for establishing the club, he was inclined to take a patriotic line. In the early 1880s, aside from the FA Cup Final, the most prestigious fixture as far as the small world of English soccer was concerned was the annual match against Scotland. Jackson believed that Scotland’s superior record in this series was due to most of its team being drawn from the Queen’s Park club. Having played together regularly there, they were likely to combine more effectively than any England team that the FA could select and, as readers of Football – one of the magazines that Jackson was editing in October 1882 – were reminded, ‘the success of a football team depends on its combination’.4 The Corinthian Football Club, its name suggestive of both soccer excellence and social exclusivity, was Jackson’s solution to this problem. Potential England players would have the opportunity of playing together regularly on Wednesdays and on tour, thereby enhancing the possibility of beating Scotland. It was this account of the club’s origins that Jackson recalled whenever he recounted the circumstances of its foundation.5 The story has been recycled many times by those who have chronicled the history of the Corinthians over the years and has only recently been subjected to critical scrutiny.

Terry Morris has questioned Jackson’s claim that Scotland had a settled side based around players from Queen’s Park.6 However, given the situation as Jackson may have seen it in 1882, his often-repeated explanation for starting the club remains plausible. For those who followed English soccer at the time, there was genuine cause for concern. ‘In the ten matches now played’, observed The Times in 1881, ‘the Scotch have kicked 34 goals and the English 20’, winning six matches to England’s two. A further 5-1 defeat for England followed in March 1882.7 Jackson recalled that it was this particular disaster that prompted him to invite ‘a few of the more prominent Association footballers in the South of England to meet in his office’, though it seems likely that the meeting at which the Corinthian Football Club was founded actually took place just after the start of the following season in October.8 England’s inferiority in terms of combination was taken up subsequently by Football when criticizing the team selected to play against Scotland in 1883 and referred to again when England was defeated a few weeks later: ‘Another contest past! Another fought and won! And won by the side that has so often proved victorious on former occasions. Why is it?’9 England was on a bad run, losing again in 1883 and 1884.

Morris, however, rejects Jackson’s ‘patriotic’ explanation for the establishment of the Corinthian club, implying that its main purpose from the start was to confront the growth of professionalism in English soccer, ‘a far greater threat to all that Jackson and his associates stood for’.10 Professionalism in Lancashire was certainly a concern in October 1882 when Football referred darkly to ‘insidious whispers’ that would soon demand the attention of the London-based FA. Some wild rumours were circulating: ‘All expenses paid. All wages paid … Hearty suppers every evening when “the team” is in training, Disgraceful orgies. Public houses and beer-shops purchased’.11 Given these circumstances, it seems odd that Jackson, having taken the initiative, should then have allowed the club to drift for two seasons. If anxieties regarding either England’s form or professionalism were pressing, they were insufficient to prompt decisive action in this respect. The 1882–83 campaign was problematic, and on occasions, it was a struggle for Archer Secretan, on whom secretarial duties had been devolved, to raise a team. Jackson himself – hardly an England prospect – turned out in the club’s third fixture when the Corinthians lost 3-1 at Brighton College.12 A comprehensive 6-0 defeat at Cambridge University was followed by a match with the Royal Engineers at Chatham for which the Corinthians arrived with only six players. Somehow, with the assistance of ‘a trio of musicians’ and two ‘subs’ supplied by their hosts, they achieved an unlikely victory, but this was most definitely not the stellar combination that had originally been envisaged.13 After this embarrassment, the Corinthians rallied sufficiently to make their first tour at Easter 1883, travelling to Lancashire to play Accrington, Church and Bootle before returning via Stoke where they lost 5-4, ‘having played one short throughout’.14

At this point and for more than a year thereafter, the prospect of the Corinthians making a significant mark on English football was highly unlikely. Only three matches were played in the season that followed, the departure of Secretan, ‘called abroad’ in October 1883, leaving both the accounts and the membership list in disarray.15 By autumn of 1884, however, when Jackson began to devote more of his time and energy to the Corinthians, it was clear that the FA could no longer ignore ‘the subtle and subversive growth of professionalism’.16 Blackburn Olympic had won the FA Cup in 1883, beating Old Etonians in the final. Their victory – the first time the trophy had been won by a team from the North – assumed huge symbolic significance, not least because it could be represented as a triumph for the plebs over the patricians.17 Extra time was required, but only 120 minutes had been enough to turn the world upside down, albeit temporarily. This match proved to be a significant watershed in English football history, but at the time, it simply increased antipathy between the ‘gentlemen’ from the South and the ‘players’ from the North. One of the Old Etonians recalled that he and his colleagues had been exhausted after ninety minutes, ‘while the Blackburn men were in strict training and they just managed to get a winning goal’.18 Critics, including Football, pointed out that the Cup-winners had trained at the seaside for a week before the final at their club’s expense, signifying ‘that the amateur clause of the competition rules is set at naught’. Concern was expressed that other clubs, including Olympic’s ambitious neighbours Blackburn Rovers, would follow this example, gaining an advantage so significant that it would ‘entirely spoil the Cup competition’.19

By mid-November 1884, when the Corinthians once again took to the field, the controversy surrounding professionalism was at its height. The focus was very much on Lancashire, especially the cotton-manufacturing towns of Accrington, Bolton, Blackburn, Burnley, Darwen and Preston, where ‘because of an intense network of local rivalries, clubs began paying or offering other inducements to good players in order to better their rivals’.20 Up-and-coming Preston North End were a particular cause for concern. ‘The Prestonian players posed as amateurs’, one newspaperman recalled, ‘but everyone knew they were not’.21 Their manager, William Sudell, after a complaint by Upton Park following an FA Cup-tie in January, had openly admitted finding employment in order to attract professionals from Scotland, justifying the club’s policy as normal custom and practice for Lancashire. Blackburn Rovers, also suspected of bending the rules, had won the FA Cup a few months earlier. Jackson at first aligned himself with those who opposed ‘veiled professionalism’, backing the rigorous imposition of the FA’s Rule 16, passed in 1882 to discourage excessive payments to cover expenses or to compensate for ‘broken time’ at work. In October 1884, this went a stage further with the introduction of three new rules designed to curb importation by prohibiting FA Cup entry to clubs that could not prove the legitimacy of players signed after 1 September 1882 or had arranged matches with opponents who had failed to meet this requirement. Their fixture lists and future gate money in jeopardy, many Lancashire clubs signalled their willingness to break awa...