![]()

Chapter 1

The four perspectives of human centered management

A systemic interrelation

This chapter will lay the foundation of what may be called a framework for delineating human centered management. Human centered management is determined by a systemic connection between various perspectives, and the intention here is to focus on this set of combinations. As will be seen, intertwining management and the human centered paradigm is much more than just a two-way relationship. It is a systemic approach that needs to combine ethics, social relations, economic effects and institutional conceptions. It is necessary then to embrace all these interrelations in order to validate the analysis. Systemic interconnectedness is an entity in itself, and it is to be studied on its own (Jiliberto 2004). So here, in order to attain a characterization of human centered management, the systemic view combines the ethical, social, economic and institutional perspectives. In the following these perspectives are briefly presented, and their interrelations are illustrated. The four perspectives will be dealt with more extensively in Chapters 2 through 5.

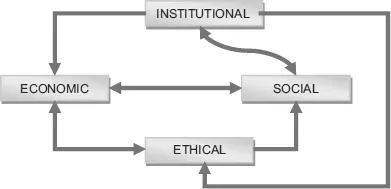

The four perspectives influence each other within a systemic interrelation as illustrated in Exhibit 1.1, and this sequence of mutual effects and feedbacks is a system of its own.

Exhibit 1.1 Interrelations between the ethical, the social, the economic and the institutional

This portrait of interconnectedness presents multiple impacts: ethical reasoning motivates social relations; it has an effect on the economic outcomes of any decision made by a leader or a manager, and it shapes the way the institutions work in a society – be they educational, legislative or judicial bodies. Conversely, institutions may inspire the ethical reasoning of decision-makers; they may frame the structure of economic activities and of societal organization. The mutual impacts continue with the interlace of social and economic occurrences and of social and institutional arrangements.

With this construct of combined perspectives, the framework given by this book differs from other setups of management ethics, which follow a pure stakeholder approach (like Bowie and Werhane 2004) or a moral principles framework (like Schumann 2001). Both moral principles and stakeholder relations are integrative parts of the multi-perspective framework as well, but the systemic dimension treats them as parts of a larger holistic entity.

1.1 The four perspectives

The combination of ethical, social, economic and institutional perspectives within the topic of human centered management makes this a complex phenomenon. Complexity is inherent in ethics issues, as they tend to be represented by different viewpoints of different people, and they are often conflictive and prone to ending up in dilemmas (Krebs, Denton, and Wark 1997; see also Poliner, Shapiro, and Stefkovich 2016, who present dilemma situations faced by educators).

This makes the phenomenon of human centered management attractive for systems theory and systems thinking. It sounds logical that the perspectives would be regarded as elements of the system of human centered management, influencing one another within this entity and exerting a combined effect on other systems (an organization, a group of stakeholders, groups of a society, etc.). But while social interaction in general has long been the subject of systems thinking, with, for example, the work of Niklas Luhmann in Germany (see Luhmann 1995) and of Talcott Parsons in the US (see Parsons 1980), the systemic aspect of leader–follower interaction has not been dealt with extensively. There is a massive body of empirical research in leadership effectiveness, but it is based on a one-way relationship; what comes closest to the morality issue is research on fairness in leadership (van Knippenberg, De Cremer, and van Knippenberg 2007).

The four perspectives will now be briefly presented within a concept that connects them to each other. This concept is multi-stakeholder dialogues. There are multiple facets in these dialogues which distinguish human centered management from routine stakeholder management. This is why after the first presentation of the four perspectives the multi-stakeholder dialogues concept will be laid out before discussing the perspectives in more depth. Multi-stakeholder dialogues, apart from being a management practice based on reciprocal stakeholder engagement, rather than on unilateral impulses for organizational control (Heugens, van Den Bosch and van Riel 2002; see also Gray 1989), have also been employed to evaluate scientific/technological advances for social/ethical and ecological risks and benefits. They promote collective learning as they uncover shared meanings and relational responsibilities. By engaging in dialogue, it is argued (Burchell and Cook 2008), ethical obligations and responsibilities are being co-constructed. The process of dialoguing with multiple partners, as it entails ethics and socio-economic considerations, requires a moral foundation as will be shown in section 1.2.

1.1.1 The ethical perspective

Leaders who acknowledge that there are universal principles that govern human behavior beyond written rules and codes act morally by nature. They abide by ethical principles in all the decisions they make, even though the outcomes of the actions they take may not always be uniform. Strict uniformity would concur with what is called universalistic ethics, meaning that an action is morally right or wrong under similar circumstances, irrespective of place, time and sociocultural context. However, universal does not mean absolute, because there maybe justifiable exceptions. This is often criticized as a casuistic position. For the casuist, the yardstick by which to measure the morality of actions is the circumstances1 surrounding the person committing the action at the time that it is committed. When circumstances, place and time vary, one should not refrain from applying a different judgment. This casuistic stance turns its attention to individual cases and to debating the relative merits of choosing a solution to a specific problem from among a number of alternatives. Leaders often find themselves in situations like this, as their moral judgment usually has to incorporate economic and social considerations.

One outstanding management scholar who recognized this interrelation early on was Peter F. Drucker. While his casuist view on ethics earned him a number of negative critics (Schwartz 1998; Klein 2000), it was from the cognition of multiple perspectives that Drucker took business ethics very seriously and developed a clear position on business morality. The social perspective in business morality was one of his foremost concerns.

1.1.2 The social perspective

All decisions made by a leader eventually have a social consequence; therefore, the impact of human centered management on society is about benefitting and advancing the condition of people. The impact of business leaders on society at large has gained increasing prominence, both in management literature, which analyzes, interprets and also reinvents this relationship, and in practice, with many individual cases of exemplary performance.

Also, a considerable number of academic and professional associations that pursue real-life dissemination have been set up, such as Business in Society LLC (http://businessinsociety.net), the Academy of Business in Society (www.abis-global.org) and the Caux Round Table (www.cauxroundtable.org), to name just a few. All are connected to and some of them are co-founders of the Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME) Initiative, which is the first organized relationship between the United Nations and business schools, with the PRME Secretariat housed in the UN Global Compact Office (www.unprme.org). This development has created a new range of concepts attempting to redefine and broaden business’ responsibilities with respect to society and introducing the idea of corporate citizenship as a core metaphor (Smit 2013). Citizenship, nowadays, needs institutions in order to fully develop, which is why the fourth perspective of conjoining leadership and morality is about institutions. Markets are the foremost institutions that are relevant for businesses, so the economic perspective is presented here before the institutional.

1.1.3 The economic perspective

There are two aspects to this perspective. One is the reverberation of moral behavior in a leader’s environment, which for business leaders means the markets. This aspect includes the impact of human centered management in business, which is discussed in detail in section 4.1.4.

The other aspect is the question of whether the economic model of capitalism promotes moral behavior or not. The most common definitions of capitalism include private ownership of the means of production, voluntary exchange of labor and goods, and competitive markets (e.g., Heilbroner 2008). The moral feature of voluntary exchange (or free markets) and competition is human freedom. But there are three contingent features (Homann 2006b):

- 1 Markets are built on a systematic feedback mechanism where buyers determine preferences through purchasing patterns.

- 2 Responsibility is clearly set in open markets. When a product or service is not acceptable to consumers, the producer has to adapt it to meet the needs of buyers.

- 3 Competition ensures innovation of goods and services as the imperative for providing effective solutions to problems and ensuring that they are rapidly disseminated.

Human freedom is a determinant, thus, for being able to choose between alternatives. This is a precedent for morality: morality is unattainable unless human beings have the freedom to choose between alternative actions or products without external coercion. Therefore, capitalism, which is free ownership in a market where labor and goods are exchanged freely, and prices are defined by supply and demand, is inextricably a system that maximizes human freedom.

The system cannot guarantee that all members of society behave morally. But as capitalism is conducive to free will, it naturally promotes moral behavior to the greatest extent possible, in contrast to an economic system where the decision-making power is concentrated in one central entity that also defines what is good or evil.

When the people of a community or country can exert their decision-making power, they will eventually opt for a capitalistic system, and it is this system that can easily adapt to the many diverse cultures of the world (Meltzer 2012).

As an additional note on freedom of choice, it should be emphasized that in order to make a moral decision (i.e., one that aims at doing good), people/leaders need to have the mental capacity to discriminate. The German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) called this attribute reason. One of the criteria he gave for assessing morality was that an act is performed not for a particular outcome but for the sake of goodness itself. What would this mean in business life? Yukl (2010, p. 334) gives an excellent example to illustrate goodness itself:

In the 1970s river blindness was one of the world’s most dreaded diseases, that had long frustrated scientists trying to stop its spread in developing countries. A potential cure for the disease was discovered by researchers at Merck. The new drug Mectizan would cost over $200 million to develop. And it was needed only by people who could not afford to pay for it. When Roy Vagelos, the CEO of Merck, was unsuccessful to get governments of developing nations to pay for the drug, it became obvious that Mectizan would never make any profit for Merck. Nevertheless, Vagelos decided to distribute Mectizan for free to the people whose lives depended on it. Many people in the company said the decision was a costly mistake that violated the responsibility of the CEO to stockholders. However, Vagelos believed that the decision was consistent with Merck’s guiding mission to preserve and improve human life. The development of Mectizan was a medical triumph and it helped to nearly eradicate river blindness. This humanitarian decision enhanced the company’s reputation and attracted some of the best scientific researchers in the world to work for Merck.

(Useem 1998, cited in Yukl 2010)

Vagelos followed what George W. Merck had enunciated 25 years earlier: “We must never forget that medicine is for people. It is not for the profits. Profits follow, and if we have remembered that, they never fail to appear” (Gibson 2007, p. 39). Now, if reason, according to Kant, leads to performing an action not to attain a particular outcome but for the sake of goodness itself, this implies that an additional outcome (the profits that follow, as stated by George W. Merck) is accepted as reasonable.

R. E. Freeman further developed Kant’s profit theory, coining the term Kantian Capitalism and relating Kant’s ideas on who has to benefit from an action to stakeholder theory (Evan and Freeman 1988). This directly connects Kant’s reasoning about goodness with the modern theory of the firm embedded on value creation as the highest business objective, with profits not an end but an effective result (Laffont 1975).

Kant’s philosophy is discussed in section 2.2.1 to highlight the importance of his theories on morality, as they are crucial for a human centered business ethics agenda and for an ethics-based stakeholder relationship framework.

1.1.4 The institutional perspective

This perspective is based on two aspects. One is the influence that moral leaders exert on institutions (with business associations being closest to business leaders although business leaders might also have an effect on other organizations, e.g., political institutions), and conversely, the motivation a leader receives from institutions.

The other aspect is that institutions are agencies with the power to deploy moral norms across organizations. This concept has been called ethics of institutions, and its basis is that a competitive market economy founded on capitalist principles and practices is sustainable with a carefully devised institutional system enabling everyone to pursue individual interests (Lütge 2005).

Institutional ethics distinguishes between actions and conditions of actions. This distinction was initially made by Adam Smith, who, besides being the “father” of free market economics, was a moral philosopher by training. In his first writings (e.g., The Theory of Moral Sentiments, published in 1759), he introduced a systematic differentiation between actions and conditions of actions, pioneering the idea of a link between competition and morality. His argument is that morality, which incorporates the idea of the solidarity of all, is the essential element in the conditions or the rules by which markets work; the members of the market act in a way that respects the actions of others. Only under these preconditions can competition be effective and foster productivity. Adequate conditions for the actors direct competition to an optimal level of advantages and benefits for all people. As the rules are the same for everybody, no one can exploit a situation where another behaves morally – everybody is induced to behave morally. This also gives an input for the discussion on whether moral managers or moral markets are more effective in mobilizing all the advantages of capitalism, which will be further explored in section 2.2.3.

The institutional perspective is directly related to issues of corporate social responsibility (CSR), maintaining that a corporation is an institution within society that has to deploy moral behavior towards other members of that society.

There are numerous organizations worldwide that offer recommendations on fostering CSR. Many of them are member-driven organizations where committed leaders work together on prin...