![]()

Chapter 1

The Image of Mecca in India

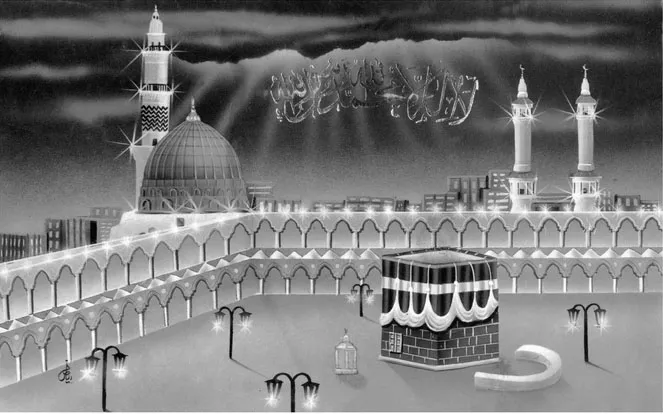

The most common icons found in almost every Muslim household are the images of two famed Arab shrines, the Ka’ba, a cubical structure draped in black and situated in Mecca, and the Gumbad-e khizra, the green dome in Medina over the mausoleum of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon Him) (Fig. 1.1). Although one is not supposed to worship them or their images, the reverence for and the desire to make a ziyārat (pilgrimage) to them is strongly instilled in the mind of every believing Muslim. Even qibla, the direction to Mecca, acquires a centrality in a Muslim’s daily life. Besides offering the customary five-times-a-day namāz (prayers) strictly facing the Ka’ba, some Muslims even find it disrespectful to lie down with their feet towards it. Frequent mentions of Mecca and Medina, along with the seerah (biography) of Prophet Muhammad and Islam’s early history, remain an integral part of every Muslim’s upbringing. These have also been referred to in much of devotional Islamic literature, in prose and poetry, in countless vernacular languages. Thus, for an Indian or a non-Arab Muslim, situated thousands of miles from these holy shrines that he or she may probably never see in real life unless fortunate enough to make a pilgrimage, simply gazing at the images of the Ka’ba and Medina fills an ocular void and further arouses the desire to visit them.

The Hajj became obligatory for Muslims at the time of Prophet Muhammad in 632 AD, although the Ka’ba had existed as a centre of pilgrimage and prayers for many centuries before the advent of Islam. Some Muslims believe it was originally built by Adam, the first Prophet, although it later got destroyed in the great flood at the time of Noah. The existing shrine, it is believed, was constructed or renovated by Prophet Abraham (early 2nd millennium BC) when he came to settle in the region after being driven out from Iraq, Syria and Palestine for practising and preaching his new faith. Following this, Mecca became a great centre of pilgrimage and trade, attracting thousands of pilgrims from in and around Arabia. Many existing rituals and sacred sites of the Hajj pilgrimage still reflect events from the life of Abraham, his wife Hajira (Hager) and son Ismail (Ishmael), including the miraculous springing of the water-well called Zamzam1 near the Ka’ba. According to Islamic belief, Abraham had advocated the concept of one God and iconoclasm, but over time pagan rituals and idolatry began to be practised around the Ka’ba, until the arrival of Prophet Muhammad a few centuries later, who cleansed the shrine of idols and reinstated monotheism through Islam.

Although he was born in Mecca, Prophet Muhammad had to migrate to Medina after facing fierce resistance from his own tribe for preaching the new faith. He returned to Mecca towards the end of his life, to perform Islam’s first Hajj pilgrimage with his supporters. Ever since, millions of Muslim pilgrims from all over the world have been annually travelling to Hijāz, the region in the Arabian peninsula parallel to the Red Sea where the towns of Mecca and Medina are situated. Visiting at least once in their lifetime, in caravans on foot, camels, ships, motor vehicles, and airplanes, pilgrims also spend time in the nearby sites of Mina and Arafat as a requirement of the Hajj, as well as Medina (400 miles north of Mecca) to pay their obeisance to the grave of Prophet Muhammad. Some pilgrims, especially Shi’as, extend their ziyārat to many shrines outside of Hijāz, such as in Iraq and Iran. Over centuries, the Hajj has emerged as one of the largest annual movements and congregations of people in the world, resulting in a significant exchange of cultures and ideas, a trading of goods and a strengthening of religious bonds. An important catalyst for creating a global Muslim identity has certainly been the circulation of the images of Arab shrines.

Fig. 1.2. A collage of the Mecca and Medina shrines on a greeting card. Publisher unknown (India), 1995. From the author’s collection.

The mass-produced pictures of the Ka’ba and the mosque at Medina have existed outside Arabia, and especially in India, since long, in a variety of forms and formats — from simple etchings and oil paintings to coloured photographs and computer-based graphics — on calendars, posters, pilgrimage guides, chapbooks, prayer rugs, ceramic tiles and, more recently, stickers, lampshades, digital clocks, and other ‘showpieces’ with blinking lights, adorning millions of Muslim households (Fig. 1.2). In a typical calendar image, the two Arab shrines, flanked by their minarets, can be seen superimposed or surrounded by the names ‘Allah’ and ‘Muhammad’ in Arabic calligraphy and a crescent and a star. Even if the theme of an image is localised (that is, showing a local Muslim shrine or a saint), the iconic Mecca and Medina are often inserted in the top corners. An Indian artist of these images, who may not always be Muslim, often improvises or adds local hues to them, some of which are even from non-Islamic iconography — not surprising given that many of these artists are involved in the production of images of all religions.

Mecca in the Early Print Culture of India

How did the earliest images or illustrations of the Ka’ba and other sacred sites of Hijāz arrive in India, and get disseminated, prior to the age of photography and mass production? It may be difficult to pinpoint an exact date for the arrival of the first image, but there are several references that give us an idea. Muslims from India have been travelling to Mecca for pilgrimage ever since Islam arrived in this region, besides Arabs themselves having trade links with India since even earlier. Some of the channels through which the image of Mecca may have been imported into India are (i) ephemera such as prayer mats, rugs, cloth hangings, ceramic tiles, and other image objects brought by Indian pilgrims returning from the Hajj; (ii) non-visual accounts, either written or oral, about the shape and size of the sacred buildings and the scenes of Arabia described by travellers or pilgrims, and passed down the generations to those who could not visit Mecca or had no access to its image; (iii) miniature paintings and illustrated books from Central Asia or Iran arriving with the travellers/conquerors; and (iv) lithographs of European origin brought by the British or the Portuguese.

One finds plenty of illustrations, originating in Arabia, Iran and Turkey, depicting the pilgrimage to Mecca and other related themes, which could have been the earliest sources of the Ka’ba’s image for the outside world, although most of these were commissioned for consumption by the ruling elite and seldom made public.2 Many Arabic and Persian sources, some dating as early as 900 AD, have described the measurements of the Ka’ba, which have changed often since the pre-Islamic times.3 One of the earliest comprehensive accounts is by al-Azraqi (d. 837 AD), who provided architectural details about Mecca’s sacred buildings in his Kitāb Akhbār Makka.4Some of these descriptions or illustrations found their way into a collective imagination about the shape of the Ka’ba in South Asia.5

Fig. 1.3. The icons of Mecca and Medina on a cluster of printed tiles on the wall of a Sufi shrine in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. Photograph by the author, 2007.

The Ka’ba has been depicted in a variety of forms in the early images (Fig. 1.3). Due to their reference from illustrated prayer rugs or illuminated books, many early paintings of the shrine show its boundary as a flat vertical rectangle made up of inner arches, small domes, few minarets, and outer gates, often labelled with names. The middle portion of the rectangle has the black-draped cube surrounded by other smaller buildings and structures, of which hardly two (Hateem and Maqām-e Ibrahim) exist today, the rest having been demolished during the shrine’s expansion post-1960. But besides this top-view scheme, many side views have also been made in Persian/Arab miniatures or European engravings. Two folios of Dalā'il al-khayrāt, a prayer book for pilgrims published in India in the 19th century, contain coloured paintings of the Mecca and Medina shrines in detailed perspective and border decoration.6 Earlier versions of this book, attributed to Muhammad ibn Sulayman alJazuli, and published in Arabia and Egypt, contain detailed illustrations of pilgrims on their way to Mecca, as well as images of Islamic festivities, displaying a rich culture of devotional visuality.

}{A number of European or Christian travellers made or claim to have made pilgrimage to Mecca, some disguised as Muslims, while a few others after embracing Islam, and wrote detailed accounts of their travels. Most famous among these travellers are De Varthema (b. 1465), Aly Bey (b. 1766), Burkhardt (b. 1784), Richard Burton (b. 1821), and Snouck Hurgronje (b. 1857).7 Some of their travel accounts published between the 18th and the early 20th centuries include lithographs showing the Ka’ba and other shrines, besides drawings of Muslim prayer posture and pilgrim caravans on their way to Mecca. Charles Hamilton Smith, an English officer, drew a wide view of the Meccan shrine in the early 19th century, showing longwinding queues of pilgrims coming from far horizons, although he probably never visited Arabia and may have sourced his information from others’ descriptions.8 It is hard to say if any of these illustrated books, published mainly for the Western reader, ever made it to India before the middle of the 19th century, but they certainly recorded and showed to the outside world the shape of Islamic shrines. Some of them also include incorrect information, such as some authors assuming the Ka’ba to be the grave of the Prophet whom Muslims worship!9

But the images circulating in Europe and America aside, the larger Islamic world was also not without its own popular print culture early on. Worth noting here is a quote from a British traveller named Eldon Rutter (who visited Mecca and Medina in 1925) about the publication and circulation of the literature and images of Mecca in the 19th-century Turkey. According to Rutter, one of the last Ottoman Sultans, Abd al-Hamid (d. 1918), who got the railways between Istanbul and Medina completed for the convenience of pilgrims, was

a wonderful exponent of the power of advertisement... The printing presses of Constantinople worked at high pressure upon the printing of the Qur’ān and books of prayers in many Muslim languages; and to this day, from Java to Morocco, it is a Muslim’s pride to possess a Stambuli Qur’ān. Pictures of the Holy Places, drawn with such startling perspective that they com...