![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

Preface

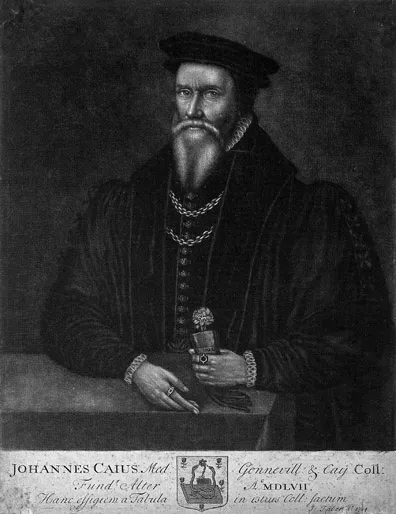

Figure 1 John Caius (1510–1573). Mezzotint by J. Faber, 1650.

John Caius’ autobibliography, De libris suis/De libris propriis, An Autobibliography, is a remarkable document that has not received the attention that it deserves. First published in 1570 as the last work in a volume concerned more with natural history, it was reprinted with corrections in 1729, and again in 1912 in the volume of his works edited by E. S. Roberts, Master of Gonville and Caius College, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of his birth. Samuel Jebb, the editor of the 1729 edition, thought it important not to forget his achievements, especially as they showed the vigour of the Classical Tradition within medicine, and most notably at the College of Physicians of London.1 But compared to his other tracts, it seems to have been little read, and in an increasingly Latin-less age, its complex High Renaissance Latin adds a further obstacle to understanding its message. Nor has it always been well served by its admirers. John Venn, whose detailed biography prefaces Roberts’ edition, described it simply as ‘a minute account of his writings, both published and unpublished’, a description that is partially misleading and hardly likely to attract readers who lack an interest in bibliography. With greater justice, another devoted Caian, Philip Grierson, declared in his introduction to the inventory of Caius’ library that it was ‘one of those tantalizing works that never tell one quite enough’. It is true that it deliberately leaves out or abridges large parts of Caius’ life, most notably the refounding of his Cambridge College and his activities at the London College of Physicians, which can be reconstructed from other sources and from what he wrote elsewhere, but these local initiatives were, in Caius’ view, secondary to the importance of his publications on the international stage. Nor does this treatise fit easily into the history of autobiography, in part because its self-fashioning is not as obvious as in many other medical lives. Besides, Caius was no Erasmus, no Thomas More, and the life of a scholar does not hold out much promise of excitement. His conservatism and, until very recently, the denigration of the standard medical theories of his age as outdated and dangerous to patients, deterred medical historians from investigating his life and writings further. His religious views and the catastrophe of his last months also diverted historians until very recently from setting him in his proper Cambridge context of the 1560s and 1570s.

Such neglect can now hardly be justified, as a variety of studies over the past two decades has shown. In this book, which crosses the boundaries of genre, Caius provides information on his life and early career that illuminates a period in English intellectual life marked by the spread of European ideas on humanism, and especially on humanism within medicine. The rediscovery of texts from classical antiquity that had been lost for centuries gave authority to those, like Caius, who revered the past and who often saw in them progress over their medieval successors. The recovery of Galen in his original Greek from the 1470s onward provided doctors of the Renaissance with an abundance of new material on therapeutics and, in particular, anatomy that proved inspirational. The book’s digressions, polemics and repetitions also allow a reconstruction of the influential Cambridge figure that others would have known and Caius wished to project. New findings, most notably of the private information contained in Caius’ own annotated copies of Galen and other volumes in his library, complement this public description of his activities and help to place him within a wider European context. He is a British writer of the Elizabethan period who is unusual in being published several times abroad and in enjoying an international reputation for his scholarship in medicine and in natural history. This short text is also a lament for the past at a point in English history when such nostalgia was frowned upon by others more progressive, and when the centuries-old synthesis of Galenic medicine was beginning to be challenged by new ideas (although it took more than three centuries before it was entirely abandoned). But to view this book in the light of what was yet to come, as has often been done, is to misunderstand much of what Caius was trying to do. As will become clear in the notes and appendices to this translation, he was far from being alone in his opinions, and he shared his intellectual interests with many leading scholars of his day.

A renaissance commentator, Filippo Beroaldo the elder (1453–1505), described the duty of commentators as being to unravel meanings, explain obscurities and uncover secrets in a chosen author.2 They should in consequence be honoured for diligently and meticulously untying any knots and for benefiting posterity by their night vigils. Beroaldo was speaking about the obscurities of the Latin poet Propertius, but his remarks apply equally well to those of John Caius. Like his hero Galen of Pergamum, Caius was a polymath. The wide-ranging nature of his publications, and the topics he chose to include in this tract, present enormous problems to any commentator. Caius’ Latin, as befits a Cambridge don, is extremely learned and allusive, and his classical references are both copious and recondite. Not all have been identified, or can be easily recognised in an English translation, and I have noted only a few of Caius’ most obvious or most surprising sources, but his contemporaries would have appreciated their range and the elegance with which they were deployed. Caius was also a doctor, working in a framework of ideas and explanations that are not those of today, as well as an Englishman living, working and travelling in Europe at a particular historical juncture as confessional differences began to harden, and adherence to the old ways could prove as dangerous, and on occasions as deadly, as a passion for innovation. A generation earlier or later, Caius would have had different priorities and different chances of success. But above all, he was a European scholar, with links across Europe and with interests that were widely shared. To recreate that humanist universe is a major task for any editor, not least because relevant material may not be easy to hand or even all located in one major library. The growing tendency of British libraries over the last decades not to purchase books in languages other than English also inhibits access to Continental scholarship, and not just to the more local publications. This insularity is partly balanced by the increasing availability of sixteenth-century texts on line, for which scholars must be immensely grateful, and of references to material of whose existence they would not have previously been aware. The chance appearance on the internet of a photograph of a traveller’s passing reference to Caius’ annotations in a study of European relations with the Levant is only the most unlikely discovery. And one should not forget, the internet has made it possible to conduct a dialogue with distant colleagues that would have been impossible a generation ago. Despite their assistance, there will still be passages that remain obscure to readers unfamiliar with Caius’ classical heritage and symbolism or whose significance in one way or another I have failed to recognise. But that is also one of the crucial features of this book, for in its language, its concepts and its expectations of its reader-ship, it is in many ways typical of the work of European intellectuals in the middle years of the sixteenth century: they travelled, they corresponded, they wrote and they believed in a community of scholars united across the confessional divide.

The life of John Caius

A few street and house names apart, John Caius (1510–1573) is remembered today only in two institutions he served loyally and with distinction, although not always to the satisfaction of his fellow-members. In Cambridge, he used his considerable wealth to re-found his old college, Gonville Hall, in 1558, providing it with new buildings in the most up-to-date Italian style. The laconic epitaph on his splendid tomb in the College Chapel, ‘Fui Caius’, ‘I was Caius’, expects the observer to know who he was, but the average tourist today is likely to be ignorant, as well as baffled by the local pronunciation of the usual name of Gonville and Caius College, Keys. The London College of Physicians, which he served as president nine times between 1555 and 1572, and whose history he wrote, displays in its Treasures Room several relics of his time, including his silver caduceus (a staff with two entwined snakes as its head). But the educational and medical ideals that he championed have long been superseded, and Caius himself soon after his death may have been reduced to a mere bit part in a Shakespearian comedy, The Merry Wives of Windsor.3 In his life-time, however, he was one of the very few English scholars to enjoy a European reputation, and the last twenty-five years have seen a rehabilitation of much of his work, and particularly that on the manuscripts of Galen described in this autobibliography.4

John Caius was born and brought up in Norwich, a city for which he retained strong affection and where he made life-long contacts.5 He dedicated one of his early works to an Alderman, Augustine Stiward, and planned, but never completed, a history of the city.6 Two other students from Norwich School, Matthew Parker and William Framingham, were later to become his friends, and both enjoyed academic careers in Cambridge. Matthew Parker (1504–1575), six years Caius’ senior, went on to become Master of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and subsequently archbishop of Canterbury.7 He and Caius shared many interests, not least in history, both in Cambridge and in London, and Caius’ writings on the history of Cambridge University drew on rare manuscripts in the archbishop’s possession.8 In the 1570s, when Caius was assailed for his opinions about religion and the proper governance of his college, and had his college rooms ransacked with the connivance, if not the participation, of the university authorities, he was still an honoured guest of Parker’s in London.9 William Framingham, by contrast with the celebrated archbishop, was a star that shone but briefly. Two years younger than Caius, he went up to Pembroke College, taking his BA in 1530/1, and immediately becoming a fellow of Queens’. His premature death in September 1537 at the age of twenty-five, was ‘a greate losse of so notable a yonge man’.10 As Caius wrote in English in 1552, in a passage summarised and turned into Latin in his Autobibliography, Framingham bequeathed to him all his writings, in Latin prose and verse. Their titles suggest that they were excellent examples of the new humanist literature, combining religious and moral exhortation in classical dress on the model of Erasmus. Caius, to whom Framingham had dedicated his book of epigrams, took on the task of preparing all this material for publication, writing commentaries to accompany the fair-copies provided for him by a pupil of Framingham, Nicholas Pergate. He had progressed so far with his task within a few months that he was able to send them off with a dedica-tory letter to the Bishop of Norwich, Thomas Thirlby (1500–1570), who was a close friend of the author.11 But Caius’ move to Italy in 1539 proved disastrous for the project. The copy was passed by Thirlby to John Skippe (d. 1552), another Norfolk man and Bishop of Hereford, who in turn sent them on to Framingham’s old tutor, Dr. Thixtill.12 Thence they passed in succession to Sir Richard Moryson (1510–1556), the English ambassador at the imperial court, John Tailor (d. 1554), dean of Lincoln and a former fellow of Queens’, and Sir Thomas Smith (1513–1577), the secretary of Henry VIII and another who overlapped with Framingham at Queens’.13 But with Smith the trail ends, and on his return to England, Caius could find no trace of the manuscripts, although he continued searching at least until the 1570s. All he could hope for was that they would turn up in the end. The ...