![]()

Part E:

Theoretical and Policy Aspects of Predatory Pricing and Competition

![]()

Chapter 12

A Case of Beer and Pretzels

William G. Morrison

1. Introduction

Predatory pricing is a notoriously slippery concept due to the apparent existence of a fine line between healthy competition (in which falling prices and increased productive efficiency benefit consumers over the long term) and the possibility of unhealthy competition (in which consumers enjoy lower prices initially only to be faced with the consequences of market power in the future). The dynamic evolutionary nature of market structures lies at the heart of the debate: how can we tell over a given period of time, whether observed competition in a market is likely to continue into the future given the possibilities of either naturally occurring or strategic entry and exit? The answer to this question depends on our ability to detect and measure behaviour that is harmful to sustained competition and consequently on our ability to distinguish naturally occurring from coerced market exit. In this paper a fictitious example is constructed to explore some aspects of predation that are especially relevant to air travel markets. In particular, the example is contrived to emphasize the importance of capacity utilization, product differentiation and product complementarities. The example is viewed through the lens of a stylized investigation algorithm developed in Morrison (2003) that captures common elements in predatory pricing rules across various jurisdictions. The algorithm highlights key decision nodes in the investigation process and the findings necessary to proceed towards conviction.

Section 2 outlines a stylized description of predatory pricing investigations. In section 3, a fictitious case is developed in which strategic interaction between two pretzel producers leads to allegations of predatory pricing. Section 4 discusses the merits and issues raised by the competition authority's case and by the accused firm's defence. Section 5 relates the issues in the case to competition between full service and value-based airlines in air travel markets.

2. Defining and Determining Predatory Pricing

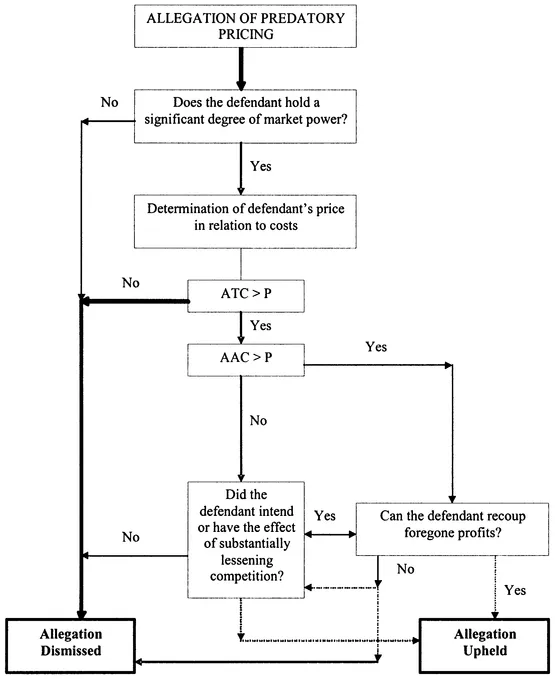

Morrison (2004) draws from an international comparison of predatory pricing legislation and procedures to create a composite stylized algorithm for the decision process underlying the investigation of predatory pricing allegations. The algorithm incorporates commonly observed elements in predatory pricing institutions around the world. Suppressing some elements and emphasizing others in the algorithm allow us to match it to particular cases or jurisdictions. Moreover the algorithm serves to highlight key differences across jurisdictions by reference to the relative emphasis placed on the various elements.

As illustrated in Figure 12.1, the algorithm has three main decision nodes, relating to the accused firm's market power and behaviour before, during and after the period of alleged predation. The first question to be asked is whether the accused firm held a significant degree of market power prior to the alleged predatory conduct. Secondly, during the period when predatory pricing is alleged to have occurred, what was the defendant's price in relation to costs of production? More specifically what was the defendant's price (P) in relation to total average cost (ATC) and average avoidable cost (AAC). This yields three possibilities:

- P > ATC

- AAC > P

- ATC > P > AAV

Thirdly following the period of alleged predation, can the accused firm reasonably expect to recoup profits that were foregone during the period of the alleged predation?

The first decision node requires that the accused firm have sufficient market power to abuse a dominant position. In many academic discussions of predatory pricing, the defendant is characterized as a monopolist, who is faced with the entry of a competitor, however in practice, market shares of 35% or more are used to define a threshold of sufficient market power.

That is, the firm must have some ability to affect the prices of competitors. The second decision in the process relates the pricing policies of the accused firm to its costs to determine whether or not the firm engaged in activities that resulted in avoidable losses. Here, the traditional standard – the Agreeda-Turner test – of prices relative to average variable cost, is often not practical given multi-product firms. Consequently, the implementation of a cost-based standard for predatory pricing has graduated towards comparing price to the accused firm's average avoidable cost, which includes product specific fixed costs and variable costs, but not sunk costs.

The second decision in the process relates the pricing policies of the accused firm to its costs to determine whether or not the firm engaged in activities that resulted in avoidable losses. Here, the traditional standard – the Agreeda-Turner test – of prices relative to average variable cost, is often not practical given multiproduct firms. Consequently, the implementation of a cost-based standard for predatory pricing has graduated towards comparing price to the accused firm's average avoidable cost, which includes product specific fixed costs and variable costs, but not sunk costs.

Considering the three possibilities in the algorithm, clearly if price is found to exceed average total costs, then the firm cannot be found to have set unreasonably low prices and an allegation of predatory pricing will most likely be dismissed at this stage. On the other hand, if price is found to be below average avoidable cost, then the accused firm can be said to have sustained unnecessary losses during the period. As such, price below AAC is at least a necessary condition for a finding of 'per se' predation and in some jurisdictions might be a sufficient condition.

Figure 12.1 A stylized predatory pricing investigation algorithm1

The trickier potential finding is a price that falls in the range between average total cost and average avoidable cost. Such a price does not define avoidable losses, yet a price below ATC nevertheless means that losses were sustained, which might still be construed as predation, particularly if prices were above ATC in the recent past. Pricing between ATC and AAC thus constitutes a 'grey area' that suffers from both conceptual and measurement problems. In such situations the competition authority may not abandon prosecution, choosing instead to look for other measures or mitigating factors, such as the intent of the accused firm's pricing policies, the relative efficiency of the alleged victim, the possibility of reputation effects resulting from the accused firm's actions and the actual or perceived extent of technical or strategic barriers to entry in the future.

In the grey area, it becomes more difficult to relate the exit of a competitor to a lessening of competition. For example Button's (2003) argument concerning the possibility of an empty core in the market could be used to provide a plausible alternative explanation of events thought to be consistent with predatory pricing.2 These measurement problems are likely to place a great deal of weight on the ability of any investigation to show pricing below average avoidable cost.

The third node in the decision algorithm asks whether the accused firm has or can recoup profits forgone during the predatory pricing period. If the defendant set its price below average avoidable cost but cannot recoup forgone profits, then in some jurisdictions (the US in particular), the allegation of predatory pricing will likely not be upheld. In other jurisdictions, relatively more weight might be placed on whether the accused firm's actions had the effect of substantially lessening competition. That is, even if recoupment is found not to be possible, reputation effects or other barriers to future entry could be used to argue that a substantial lessening of competition occurred. The dotted lines in Figure 12.1 indicate that several decision paths are possible here, depending upon the legislative focus.

In the next section I develop a fictitious market interaction between two firms who produce pretzels. This example deliberately de-emphasizes the pre-predation dominance and post-predation recoupment questions in order to focus upon the measurement and inference of price in relation to costs d...