Part 1

Party System Continuity or Change?

1

On Mistaking a Dominant Party in a Dealigning System

Asher Arian and Michal Shamir

The 2003 elections were much more than simply another gyration of the Israeli political wheel of fortune. They offer clear evidence of a further weakening of the left in the ongoing shift to the right and to the Likud, as the analysis of the election results and the surveys conducted between 1969 and 2003 indicates. But the shift to the right has not meant the successful emergence of the Likud as Israel’s dominant party.

Transformation in a society and its political system is a complex matter. Rules of the game change, new groups of voters emerge, and international and economic realities are in constant flux. Realignment and dealignment are two concepts that are useful in understanding political change and interpreting electoral dynamics (Dalton, Flanagan and Beck, 1984). These two concepts are grounded in different models of politics. The realignment concept is tied to a social cleavage model; the dealignment concept is rooted in a functional model that evaluates parties and party systems in terms of their relevance to society and politics. A partisan realignment involves significant shifts in the strength of party coalitions, and in their ideological and social group bases. Dealignment is characterized by the increasing volatility and unpredictability of elections, as well as by a weakening of parties and party bonds as a long-term and permanent feature of the system. Realignments are volatile as well, but only in the short run—until new party alignments take shape.

This conceptual frame is helpful in considering shifts in Israeli politics since the Six Day War in 1967. The thrust of our argument is that the Israeli party system has undergone both realignment and dealignment. The right-wing realignment culminating in the 1977 Likud turnover victory is still in effect, while at the same time, there has been a dealignment in the system. The 2003 election consolidated the 1977 realignment, while at the same time continuing the dealignment processes of the 1990s.

The Israeli political system in the last decade has been fluid, unstable, and changing. There has been a loosening of traditional allegiances in favor of new alignments, obscured by the major structural change of the direct election of the prime minister. This change, in effect between 1996 and 2001, made the system more unpredictable and left it in greater flux, further weakening the bond between voter and political party. In addition, there was a systematic relaxation of the ties that had hitherto brought many voters to identify with the dominant left/Labor party camp, thus facilitating a steady shift of voters to the nationalist right/Likud bloc.

I. The 2003 Election—Consolidation of the 1977 Realignment

After the Six Day War, Israel was preoccupied with the politics of peace and security, with policies aimed at achieving a secure future for Israel in the Middle East, and with the future of the territories taken during the 1967 war. Fissures between and within parties were related to the scope and timing of a withdrawal from the territories and the likely impact that any move would have on the security situation. Most parties and most voters agreed that no movement was possible without recognition of Israel by the other side and without direct negotiations. Demands for recognition and direct negotiations froze any possibility of moves being taken for years to come.

When developments did occur, they were very slow. In 1978, Egypt and Israel signed a peace treaty that involved the withdrawal of Israel from the Sinai Peninsula. In 1993, the Oslo Accords signified the mutual recognition of Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization, and, in 1994, Israel and Jordan signed a peace treaty. These developments had the support of Israeli public opinion, which, at certain junctures, even led the way (Arian, 1995; Shamir and Shamir, 1993).

The 1977 election turnover signaled a realignment of the party system, of the electorate, of the elites, and of public policy. Ethnic and religious group allegiances crystallized, and demography, combined with the sharp split over the territorial issue, led to a redefining of the political system. From among an electorate that identified with positions espoused by the Israeli “left” there was a surge of support for the “right” and its symbols (Arian, 1975, 1980; Goldberg, 1992; Shamir, 1986). After having been dominated by the Labor party until 1977, the party system became increasingly competitive. Before 1977, the question decided by elections was which party would be the second largest, since it was a foregone conclusion that Labor would have the greatest number of Knesset seats. After 1977, the question was now which would be the largest party, and what was the likelihood that it would be capable of forming a coalition that could survive in the face of frequent crises. This pattern was strengthened rather than diminished by the aborted direct election of prime minister electoral system; the question then became which candidate in the prime ministerial race would get the most votes, rather than which would be the largest party.

The first turnover election after 1977 was 1992, and it was significantly different from the 1977 election (Arian and Shamir, 1993). It was followed by mutual recognition with the PLO, a shift that marked as abrupt and dramatic a change as that which followed the ascent of the Likud in 1977. However, the electoral shift in 1992 was less complex and numerically smaller than that in 1977 and was grounded more in issue positions than in social groupings. It did not result in a notable or enduring restructuring of the power distribution and the political cleavage structure. There was no realignment in 1992; nor were the two following elections of 1996 and 1999—which implemented the direct election of prime minister system—elections of realignment.

The high level of competitiveness and the consecutive shifts in power that characterized the 1990s obscured the underlying shift to the electoral right. Other factors that masked the shift were the proliferation of National Unity governments in Israel during this period and the public opinion and policy shift toward more flexible positions vis-à-vis the Palestinians. More politicians in power pursued policies long championed by the left, and public attitudes became more conciliatory. Territorial compromise, recognition of the Palestine Liberation Organization, and willingness to condone the establishment of a Palestinian state are examples of that shift. Yet, at the same time, more voters were opting for parties and symbols of the right.

The Likud was in power for most of the period following its 1977 victory despite the high degree of competitiveness that characterized the end of Labor’s dominance of Israeli politics. The Likud prime ministers were Menachem Begin (1977-1982), Yitzhak Shamir (1982-1984, 1986-1992), Benjamin Netanyahu (1996-1999), and Ariel Sharon (2001-2003). By contrast, the Labor prime ministers seemed to signal a counterpoint to the Likud theme (Shimon Peres [1984-1986 and 1995-1996], Yitzhak Rabin [1992-1995], and Ehud Barak [1999-2001]).

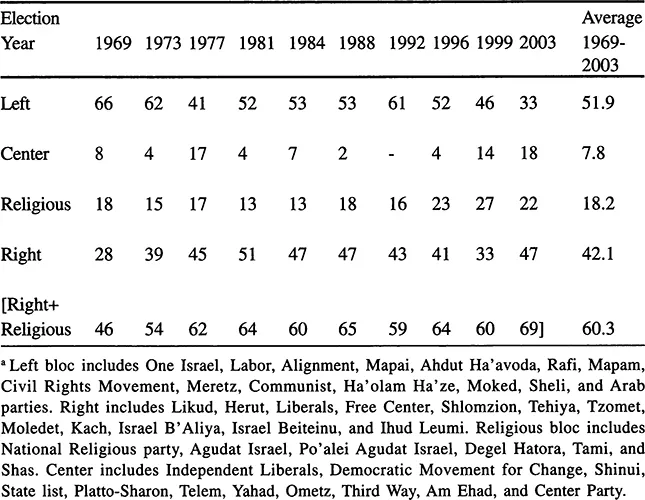

In the ten elections between 1969 and 2003 (see Table 1.1), the right bloc consolidated its domination while the left lost support. While the left bloc managed three times to achieve an absolute majority of the 120-seat Knesset in that period—which the right never did —the right and the religious blocs in tandem have won sixty or more seats in every election since 1977, except for 1992. Here, the right and the religious parties are lumped together since they often shared governmental power in this period and usually had similar policy orientations, especially with regard to the territories.

If we compare the power relations in 2003 to previous elections, as in Table 1, it is apparent that 2003 is most similar to 1977—only the shift in power is even more pronounced. A gauge of long-term performance is provided by considering the average number of Knesset seats won by each of the blocs in the last ten elections, compared with their strength in 2003—this affords a sense of the relation between the 2003 results and the aggregate political history of the last thirty-five years. It comes as no surprise that the left bloc is the big loser. Moreover, the losses of the left are greater than the gains of any of the other individual blocs. The left bloc’s average of seats won over ten elections was 51.9 and their victory in 2003 amounted to only 33, a drop in seats of 18.9. The right bloc average was 42.1, indicating that their 47 seats in 2003 was 4.9 seats better than their average performance.

Table 1.1

Knesset Election Results, by Blocs,a 1969-2003

The religious camp did poorly in 2003 only when compared to its unusually strong showing in 1999. But in terms of the ten-election results average their 2003 showing was actually 3.8 seats better. The center (mostly Shinui) was the big winner in 2003; compared to the average over ten elections, they were 10.2 seats ahead.

And if the right and religious blocs are added together one gets a true sense of the dynamic at work in the system over thirty-five years. The right and the religious on average won at least eight Knesset seats more than the left. The left and center together were about equal to the right and the religious, but this does not reflect the actual political situation because generally, in the period under consideration, the left and center were competing with one another over policy and patronage while the right and religious were cooperating, and also because by its very nature, the center oscillates and changes sides more readily.

The 2003 election thus continued the trends of the previous three decades, further consolidating the decline of the left and the right’s control over the parliament, policy agenda, and the nation’s priorities. The strength of the two large parties, Labor and Likud, had declined significantly throughout the 1990s; in 2003, the right-wing Likud doubled its Knesset representation to 38 seats, while the left-wing Labor saw a further decrease. After the 2003 election there was a single party (Likud) clearly at the top of the heap. Ariel Sharon in 2003, like Menachem Begin twenty-five years before him, was the victor over the left (with the help of a break-away center party); he held uncontested power and was positioned to make historical decisions regarding the future of the territories.

II. Ascendancy of the Right

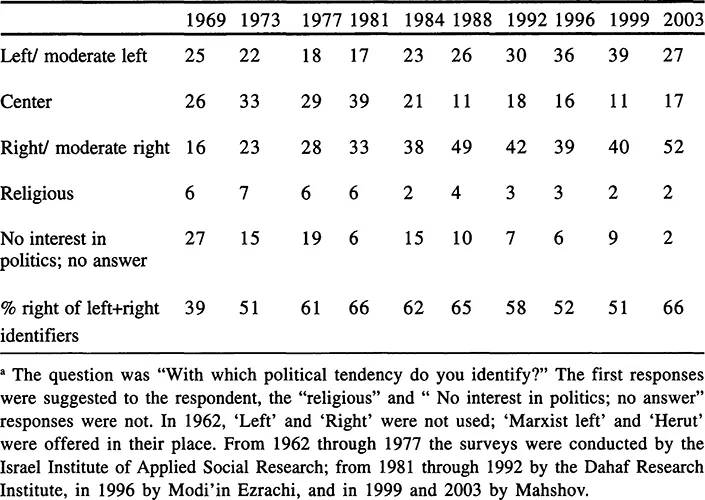

Individual-level data1 buttress this analysis and offer another view of this process. Voters’ self-identification (that is, how voters identify themselves) on the left-right continuum not only indicates ideological tendencies, but also—and primarily—political affiliations (Arian and Shamir, 1983). Table 1.2 presents these data, and we obtain a picture very similar to that generated by the power shifts that occurred as a result of the Knesset elections between 1969 and 2003, portrayed in Table 1.1.

Table 1.2

Left-Right Self-Identification (in %), 1969-2003a

The dominant-party system that finally collapsed in 1977, in which many more identified with the left than with the right, had been gradually eroding before then. In 1973, the two camps were about equal in size. By 1977, with the turnabout in government, the right superseded the left. The right continued to grow until 1988, when it comprised almost half the Jewish population, but during the peace process years of the 1990s, its upsurge halted and its strength decreased. The fortunes of the left presented a mirror image, hitting low points in 1977 and 1981, after which it increased in size. Voter identification with the left reached its high points in the 1990s with the peace process unfolding, with the lessened security threat and with increased hope at the prospect of a peaceful resolution to the Arab-Israeli conflict. By 1999 the size of the two groups was again almost equal. In 2003, over two years into the Al-Aqsa Intifada, the left had dwindled by almost 30 percent, and a majority of those surveyed identified with the right—an unprecedented finding in such surveys.

Another trend observable in Table 1.2 is the growing relevance that the left and right labels have had since the end of Labor’s dominance. These labels organize the multi-party system, combining politics and ideological stance, and are used by politicians, political commentators, and the general public. As the two-bloc party system established itself, beginning in the 1980s, the terms “left” and “right” became more meaningful, useful, and prevalent, and over time there was an increase in the number of respondents defining themselves as one or the other. By 1988, 75 percent did so, compared to 50 percent in 1981, and 45 percent in 1969. In the 1999 and 2003 surveys, 79 percent identified themselves with one of the two blocs. The depletion of the center category and of the ranks of those who identify with no bloc is the flip side of the same process. If one adds together along the continuum those who identified themselves with the center and those with no identification, one obtains a convincing trend. This group declined in size from about half of the sample up to and including the 1981 elections, to about a third in 1984, dropping to between a quarter and a fifth of the sample in the next five elections.

Another reflection of changes in the party system can be seen in the responses of those who identified themselves as religious using this gauge. Through the 1981 elections about 6 percent were unwilling to identify themselves in left-right terms and voluntarily identified themselves with the religious camp. From 1984 on, this number shrank by about half, as the religious dimension became increasingly associated with a hawkish, right-wing position on the subject of the Arab-Israeli conflict—the major dimension of the left-right continuum. This dimension of political identification evidently overrode other calculations for many religious voters.2 These data provide additional justification for our decision to group together the religious and right as one bloc in our analysis of the political dynamics of this period.

The electorate had become increasingly identifiable using “left” and “right” labels and had also become more polarized, with fewer center and non-identified respondents, and with more identifying with left and right, respectively. If we take only those respondents who defined themselves as either left or right, in each and every election since 1973, there were more Jewish voters identifying with the right than with the left (last row in Table 1.2). In 2003, as in 1981 and 1988, two-thirds of the total left or right identifiers chose the “right.”

The most polarized years according to these data were 1996 and 1999 during the Oslo period, when the number of left and right sympathizers was nearly equal. In 1973, the number of left and right sympathizers was also almost equal, but their combined number was much lower than in the 1990s, and there was thus less overall polarization of the system.

In any case, both the survey data and the analysis of the election results establish the longitudinal surge to the right, and in this sense one can speak of a consolidation of the 1977 realignment. Also, as we have shown in the introduction, in terms of voter alignments, the 2003 election exhibits no new pattern compared with the past: the young, the less well-to-do, the more religious, and the Mizrahim all tended to the right, whereas the older, secular, better-off and more highly educated Ashkenazim voted for the left (see Shamir and Arian, 1999). Of course there was a decline on the left, and the center (mainly Shinui) did extremely well at the polls, appealing especially to the young, the middle class, and the secular. While Shinui’s surge was impressive, it cannot be seen as the sign of a distinct and long-term shift in voter alignments, a topic to which we will return in section IV of this chapter.

Beyond the dramatic decline of the left at the polls in 2003—far below its previous low in 1977—and the concurrent surge of the right, are there any other indications of an emergent dominance of the right and the Likud? Table 1.3 provides a few more clues, using a love-hate thermometer for the two major parties, a left-right placement scale for these parties, and a left-right self-placement scale based on post-election surveys in 1996 and 2003 (see Table 1.3).3

In 2003, on a scale between 0 (left) and 10 (right), the sample placed itself to the ...