![]()

1 Westfield's architecture, from the Antipodes to London

Scott Colman

The two recently opened (2000 and 2011) Westfield shopping complexes bracketing central London receive near thirty and forty-five million annual visitors respectively.1 Both are ‘hardwired’ into the city’s railway system, are located near major road arteries, and occupy legacy sites of the industrial city. The two complexes form a pincer movement that isolates, up-scales, and antiquates the central city. They are the largest and most advanced investments of a retail conglomerate with over a billion customers a year. Historically an Australian company that began with the importation of the American mall typology to Sydney in the late nineteen fifties, the Westfield Corporation has been savvy in the financing and ‘curation’ of its facilities and strikingly innovative in the realm of design.2 The firm’s growth was born of a willingness to engage architectural experimentation within unique urban conditions. Realizing the importance of the nexus between public and private transportation in Australian cities with commuter rather than metro rail systems, Westfield capitalized on a retail environment with highly regulated trading hours. They developed a dense, vertical shopping typology that has proven more successful in the contemporary city than its American cousins. Moreover, the scale and expertise required to finance, develop, and manage this architectural typology played a significant role in the success of the corporation, allowing its descendent companies to become major forces in the global retail sector and contemporary urban development. A mutation of the Australian model, the London complexes are paradigmatic of a new kind of shopping centre. Through their size and connectivity, they conceive a new scale of city building. Integrated with and dependent upon the infrastructural legacy of the twentieth-century city, these new complexes ‘hack’ existing urban transit networks to constitute the nodes of a radically transformed urban realm.3

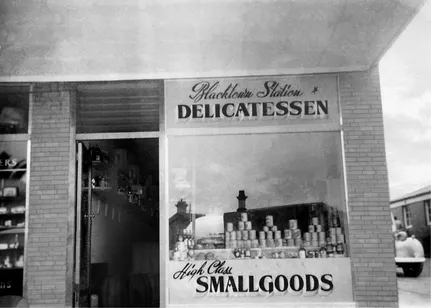

Figure 1.1 Frank Lowy’s and John Saunders’ Delicatessen opposite Blacktown Station. Source: Courtesy of the Westfield Corporation

A progressive shopping centre

In 1953, two recent Hungarian immigrants to Australia opened a continental delicatessen opposite the railway station in the then-peripheral Sydney suburb of Blacktown (see Figure 1.1). On weekdays, following the arrival of each train, the store flowed and ebbed with commuters arriving home from the central business district thirty-five kilometres away.4 Frank Lowy and his friend John Saunders had realized the value of a well-located and pleasurable convenience. Situated at an intermodal transportation junction – the interchange between locomotion and perambulation, and between work and home – the small delicatessen inserted itself into the everyday habits of this small suburban community. The corporation Lowy and Saunders would soon establish developed this geographic retail strategy into an art form. In 1960, when the company went public under the name Westfield, it included two shopping centres and two residential investments.5 A half-century later, in 2009, the organization’s market capitalization was A$29 billion and it was the largest retail property group in the world.6

The history of the Westfield Corporation and the particular kind of shopping centre it developed is inextricable from the development of Sydney in the second half of the twentieth century. Although the railway heading into the mountains west of Sydney had reached Blacktown by 1860 and electrification of the Sydney network had begun in 1926, the rail line to Blacktown had only just been electrified when Lowy and Saunders opened their delicatessen. Between 1954 and 1961, the population of the area more than tripled. Many of the delicatessen’s customers were recent European immigrants themselves, drawn to the area by this newly efficient connection to the city centre, nascent industry, and relatively cheap, newly subdivided land. Catering to the tastes of this immigrant community, the partners opened a coffee lounge a few doors down from the delicatessen and then leveraged these initial commercial successes into a number of speculative property ventures, initially residential and small retail, but then, most notably, the development of an open-air shopping mall, which opened in Blacktown in 1959.7

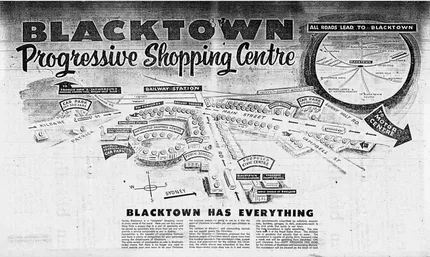

As a promotion for their ‘Progressive Shopping Centre’ makes clear, Lowy and Saunders conceived their development within the optimism of the late fifties (see Figure 1.2). Australians, torn between colonial loyalties to Britain and the realities of their place in the Pacific during WWII, increasingly saw any turn to the United States as a shift to the future. Westfield Plaza was consciously and conspicuously an American import, providing fifty parking spaces, accommodating two small department stores and twelve shops centred on a garden courtyard, and flaunting colourful ‘American’ plastic finishes. Saunders and Lowy had been following American developments in the retail literature and, during the development of Westfield Plaza, Saunders travelled to the United States to obtain knowledge of precedents first hand. Both partners would travel across the Pacific on an annual basis in the coming decades, maintaining a keen eye on emerging industry practices as they became formidable players in the Australian market.8

Figure 1.2 Advertisement for Westfield Plaza, c. 1959. Source: Image provided by the Westfield Corporation; courtesy of the Blacktown Advocate

Despite its modern American styling, in its urban strategy Westfield Plaza was a hybrid. Humbler than leading US developments of the time, it was neither an autonomous suburban centre, nor exclusively automobile-oriented. Seeking to repeat their initial commercial successes, Lowy and Saunders acquired land near the train station, taking advantage of the patronage provided by the nearby station parking and the expanding bus network that ferried train commuters into the burgeoning surrounds. Blacktown was a regional hub at the junction of the western line and a branch to the northwest; it conjoined areas north and south with the Great Western Road, the main vehicular artery into Sydney’s western hinterland. Depicted as a coliseum or open theatre and situated alongside the post office, a public school, and the rapidly growing suburb’s proposed civic facilities, Westfield Plaza was not in competition with, or a substitution for, the historic centre and the civic realm; it was integrated with them. Like the delicatessen and café, Lowy and Saunders conceived commercial development connected to a network of public infrastructure, complementing public services with socially oriented retail activity.9

In this respect, Saunders and Lowy may have been influenced by the two earlier American-style shopping centres in Australia, both of which opened in 1957. Australia’s first – Chermside Drive-In Shopping Centre, an air-conditioned mall in suburban Brisbane, with 700 parking spaces – was sited, like many of its American cousins, alongside one of the city’s principle road arteries, as was the smaller, open-air development opened six months later, with 400 parking spaces in the Sydney suburb of Top Ryde. Yet, like Westfield Plaza, both were located at transportation nodes, proximate to growing suburbs established at the termination of a spur in the city’s tram network.10

While these early centres were tethered to historic urban cores by public transportation, in the subsequent half-century, as the Australian suburbs rapidly expanded, numerous new shopping centres were constructed beyond the reach of the public transportation system, often on greenfield sites with convenient connections to major roads. Moreover, as early as 1965, the most celebrated of Sydney’s modern shopping centres, Roselands, developed by the department store Grace Bros., and conceived as ‘a city in the suburbs,’ was sited at a distance from the two rail lines connecting the area to the central business district. Like the Myer department store company, which had ignored nearby train stations in the Melbourne suburb of Chadstone in 1960, Grace Bros. was embracing an automobilized future, driving a stake into the heart of their struggling downtown competitors.11 Grace Bros. executives returned from their US research trip with the vision of an inward-looking community centre incorporating a three-storey department store, a grocery store, ninety-seven specialty shops, childcare facilities and other patron services, a cinema, doctor’s surgery and dental clinic, post office, food court, restaurants and cafés, organized around a central, double-height internal atrium, and featuring meandering paths, modern artworks, aviaries, gardens, and fountains.12 In this car-oriented strategy, the shift from mechanized to pedestrian movement had to be precipitated by a destination. By contrast, in the investments that established its dominance of the Sydney market, Westfield capitalized upon existing intermodal transportation exchanges.13

The intermodal model

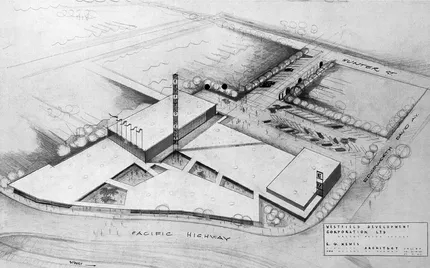

Westfield’s first major investment as a public company, a centre with twenty-two shops, and department, hardware, and grocery stores, opened across from the train station in the northern Sydney suburb of Hornsby in 196114 (see Figure 1.3). Like Westfield Plaza, it was organized around an outdoor, landscaped, social space, now conceived as a pedestrian street, with wide openings that allowed views into the complex from the train station and passing automobiles on the Pacific Highway, the major northern artery of the city. Deftly establishing the emerging habits of the Sydney commuter, the Hornsby centre’s ample circulation connected train commuters with its parking lot and the surrounding residential fabric.

Figure 1.3 E.G. Nemes, design for Westfield Hornsby, 1960. Source: Courtesy of the Westfield Corporation

The centre Westfield opened near the Burwood train station in 1966, was, like Roselands, completed in the previous year, entirely air-conditioned and, despite its location on an existing commercial high street, was conceived – at least in branding if not programming – as a self-contained town centre. The new Brisbane centres in Toombul and Indooroopilly, which opened in 1967 and 1970, were built across from train stations, incorporating regional bus ranks. Subsequent Sydney centres, whether new construction at Liverpool (1971), Parramatta (1975), and Hurstville (1978), or the expansive redevelopment of acquired shopping centres at Miranda (1969), and, more recently, Chatswood (1987), Bondi Junction (1995), central Sydney (2001), and Penrith (2005), all engaged and intensified an existing hub of transportation, retail, and business activity.

Encumbered with a difficult geography and, by American standards, an undeveloped, chronically overburdened, and until recently, fragmented freeway system, Sydney, due to its well-established train system, is more frequently punctuated than its trans-Pacific cousins with suburban nodes. Like other Australian cities, it has a ‘commuter train’ network, which, by comparison with a ‘metro’ or ‘underground’ system, is characterized by less frequent, higher-capacity trains and larger distances between stations. Therefore, Sydney’s manifold sub-centres are less evenly spread, more distant from each other, and more dominant of their surrounding fabric than in London. There are fewer high streets in Sydney than there are in London, particularly toward the periphery, but they are relatively more significant, and, because connected by public rail to the central city – even today the dominant site of business and employment – they are the destination of often privately owned local bus routes and regional automobile traffic. Strategically located at these crucial junctions, Westfield’s Sydney complexes have grown and thrived while malls premised on automobile dependence, such as Roselands, have withered.

Westfield’s Sydney complexes were designed to encourage, attract, and attenuate pedestrian movement at these junctions. Siting them as close to train and bus stations as possible, and often incorporating the latter, Westfield sought to provide large amounts of parking situated and accessed in ways that encouraged ‘footfall’ within the centre itself. Although there was little significant historical fabric offering resistance to development in these suburban centres, the extant commercial property – usually small, two- or three-storey buildings with shops and professional offices – was costly by comparison with peripheral development. The aggregation of capital and land was not particularly hard won on greenfield sites or when investment was still thin on the ...