![]()

1 Housing and shifts to a post-growth society

Introduction

This chapter examines changes in Japan’s housing conditions within the post-growth context, placing particular emphasis on the shrinking of the housing market and the widening of housing inequalities. Many mature economies have begun to experience post-growth social changes characterised by slower economic growth, ageing of the population, lower fertility, and increasing social stratification. Japan stands at the leading edge of such transitions into a post-growth society, providing a vivid case study with regard to housing developments after the era of high growth. The chapter begins by examining the nature and characteristics of Japan’s post-war housing system that was developed in the growth period. This is followed by identifying key elements such as the demographic, economic and policy shifts that are shaping post-growth social changes. It then moves on to analysing the shrinking of the housing and mortgage markets and the role of housing in reorganising inter- and intra-generational social inequalities. Finally, the chapter highlights the importance of the post-growth context in light of exploring contemporary housing and social processes, providing a basis for the subsequent chapters to examine more specific issues.

Building the post-war housing system

It is necessary to investigate the development of the housing system during the high-speed economic growth period before analysing emerging housing conditions in the post-growth era. Japan’s housing system during high growth was characterised by particular orientations towards facilitating mass housing construction and promoting home ownership among the emerging middle class (Hirayama, 2003, 2014). The post-war Japanese state was characterised as a ‘developmental state’ that prioritised and orchestrated economic development as a means to legitimise itself and to sustain social stability (Fukui, 1992; Institute of Social Science, the University of Tokyo, 1998; Murakami, 1992). Within this framework, the housing system was directed at the acceleration of the mass construction of owner-occupied houses, where an increasing number of households were encouraged to own their own homes.

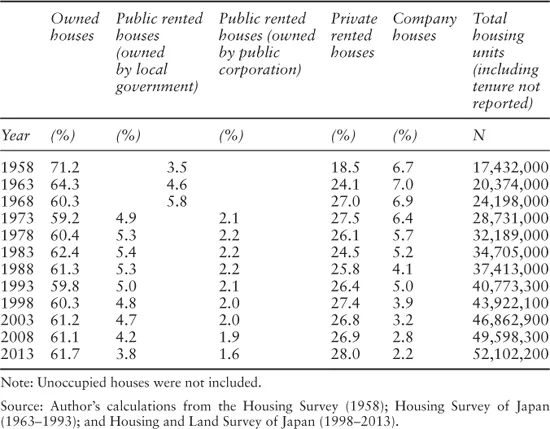

The government established post-war housing policy based on the ‘three pillars’: the Government Housing Loan Corporation (GHLC) Act in 1950, the Public Housing Act in 1951 and the Japan Housing Corporation (JHC) Act in 1955. The GHLC provided middle-income households with long-term, low-interest loans for building or purchasing their own home. Public housing was allocated to low-income households at low rent, while the JHC together with local public corporations constructed multifamily apartment complexes for both rent and sale for middle-income households. Of the three pillars, the supply of the GHLC’s loans was particularly emphasised as a means to facilitate middle-income home ownership. According to the Housing and Land Survey (see Table 1.1), since the 1960s, despite rapid urbanisation, with the provision of GHLC loans aimed at encouraging home ownership, the level of owner-occupation has been maintained at approximately 60 per cent, representing its position as the dominant housing tenure. The ratio of private rented housing has been the second highest, accounting for a little more than a quarter of all dwellings – for example, 28.0 per cent in 2013. However, the government has not supported the provision of private rented housing. There has been little assistance for the construction of private rented units and almost no provision of cash-based rent subsidies. The direct provision of rental units by the public sector was positioned as a residual measure (Harada, 1985; Ohmoto, 1985). The ratios of means-tested public housing for low-income households and public corporation rented housing have been minimal – 3.8 per cent and 1.6 per cent in 2013, respectively. Japan’s housing policy has thus been characteristically tenure biased (Hirayama, 2014).

Table 1.1 Housing tenure in Japan (1958–2013)

Within the framework of the developmental state, post-war housing policy not only served to provide housing but was also operated as an engine for economic growth (Oizumi, 2007). As a result of post-war high-speed economic growth, Japan became the world’s second largest economy by 1968. From the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, the average annual GDP growth was approximately 10 per cent. The construction, housing and real estate sectors played a leading role in driving economic development. The ‘iron triangle’ between the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), government bureaucrats and the construction sector, which constituted the political core of the developmental state system, was devoted to encouraging mass housing construction (Honma, 1996). The LDP, a party of established conservatives, has held power almost exclusively since it was founded in 1955. The government led by the LDP provided many households with GHLC mortgages, which was instrumental in accelerating housing construction. This in turn led to the maintenance of political support for the LDP by the construction industry as well as the housing and real estate sectors. With the enactment of the 1966 Housing Construction Plan Act, the government began to draw up Five-Year Housing Construction Plans periodically as a foundation for housing policy. The majority of public funding for housing construction took the form of GHLC loans. The strategy of the conservative administration was focused on expanding the construction of housing, especially owner-occupied housing, by indicating a targeted amount of housing production.

With the oil crisis of 1973 as a turning point, housing policy became more of a measure to stimulate the economy. Although the economic climate recovered after a short recession caused by the crisis, the era of high growth ended and a period of low growth began. This shift led to further strengthening the ‘iron triangle’ – the politico-economic relationship between business, especially the construction industries, the bureaucracy and the ruling LDP. The government further geared housing policy towards the mass construction of owner-occupied housing in order to revitalise the economy, providing more incentives for households to purchase their own home with GHLC loans. As a consequence, since the early 1970s, among the three pillars of housing policy, only the construction of owner-occupied dwellings was promoted, while the public rented sector was further residualised.

The post-war housing system of encouraging an increasing number of middle-income households to acquire an owner-occupied house was expected to create and maintain a ‘social mainstream’ (Hirayama, 2003, 2014). Backed by the rapid economic development, the increased flow of households who ascended the ‘housing ladder’ towards entering the home-ownership sector led to the spread of middle-class lifestyles to wider segments of society. The government formulated tenure-biased housing policy, placing emphasis on expanding the home-ownership sector, where housing measures for low-income households were marginalised. Public funds for housing were therefore not largely redistributed but rather concentrated on middle- to high-income households that wished to purchase a house. This was rationalised and justified as a means of providing more households with opportunities to climb up the ladder towards property ownership as membership in the social mainstream.

Within the context of shaping the social mainstream, the government implemented family-oriented housing policy and advantaged conventional family households in securing housing while excluding unconventional households (Hirayama, 2003; Hirayama and Izuhara, 2008). For example, the GHLC did not provide one-person households with mortgages until 1981. Of single-person households, GHLC loans were only available to those aged 40 or older until 1988 and to those aged 35 or older before 1993, when the age restriction was eventually removed. In addition, the GHLC did not provide mortgages to those who wished to build or purchase small houses. This was aimed at encouraging the construction of spacious ‘family homes’ while at the same time implicitly excluding one-person households. The public housing schemes for low-income people also excluded one-person households. It was only in 1980 when the elderly single-person households had become eligible for public housing as a result of a court battle (Kawano et al., 1981). However, younger single households continued to be excluded from public schemes. The JHC provided rental housing mainly to family households with a small number of dwellings for single-person households. Thus, only people who established a family household centred on marriage counted as legitimate members in mainstream society and were regarded as worthy of government support.

In parallel to housing policy, the taxation and social security systems have favoured family households. The family system in Japan was traditionally based on the ‘male breadwinner family’ model (Yokoyama, 2002; also see Chapters 4 and 5 for more discussion). Within this framework, married women, or homemaker wives, who may be part-time workers on low wages, have been provided with an entitlement to a basic pension without having to make contributions while assisting their husbands in qualifying for income tax deductions. In the labour market in Japan, the status of women has been much lower than that of men in terms of stable employment, promotion opportunities and remuneration. This has combined with the tax and social security systems that have given institutional advantages to male breadwinner families to prompt many women to get married.

Moreover, the development of Japan’s post-war housing system was linked to the formation of a ‘company society’ (Fujita and Shionoya, 1997). Major companies adopted the systems of life-long employment and seniority-based promotion and salary while providing employees with a variety of occupational welfare, including housing assistance (Sato, 2007). The government supported the security of employment and facilitated the provision of occupational benefits by means of regulatory measures and tax incentives. Corporate-based housing measures were placed in the Japanese housing ladder. Low-rent employee dwellings and rent subsidies were supplied for young employees, while employees at higher rungs of the ladder had access to a company loan system for house purchase. The occupational welfare system of major companies was characteristically aligned with the male breadwinner family model. Employee dwellings as well as family allowances were only provided to male employees whose spouses were housewives or part-time workers, corresponding with the tax and social security systems.

In addition, the home ownership system was situated within the framework of the ‘Japanese style welfare society’ (Hirayama, 2014). From the late 1970s to the 1980s, it was well debated whether or not European welfare state models were applicable in Japan, considering the contrast between Japan’s growing affluence and a continued low level of state welfare. With a decline in growth rates in the 1970s, however, LDP politicians and government bureaucrats began to stress the necessity of developing a Japanese-style welfare society (Shinkawa, 1993). The basic idea was to revitalise the traditional Japanese practice of reciprocal help and to define families and corporations combined with property ownership as the cornerstone of the welfare system. According to the conservatives, the European welfare models were not necessarily desirable due to high dependence on public resources, while Japanese values and practices were effective in maintaining the nation’s vitality. The LDP government used the term ‘welfare society’ while avoiding use of the term ‘welfare state’, denoting its intention to rationalise the limited development of state welfare. Within this framework, property ownership combined with the family and company systems has thus constituted the foundation of Japan’s welfare approach.

Entering a post-growth era

Demographic change

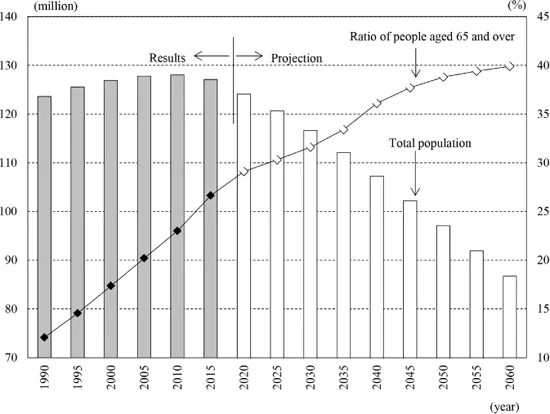

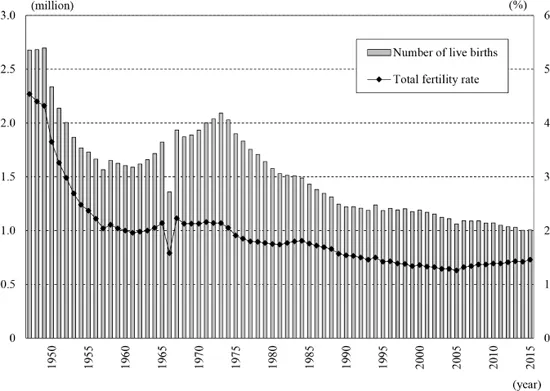

The condition of the housing system was fundamentally transformed following the end of high growth. In this section, we identify three key ingredients that constitute post-growth social transitions for our explorations of housing developments, namely, shrinking and ageing population, continuing economic stagnation, and policy changes towards a more neoliberal direction. First and foremost, demographic decline is one of the most important elements responsible for Japan’s shift to a post-growth society. According to the 2012 projection by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, the population, which was 128 million in 2010, is predicted to decline significantly to 107 million by 2040 and then to 87 million by 2060 (see Figure 1.1). This is partly due to Japan’s ultra-low fertility. The total fertility rate (TFR) in Japan, which was more than 2.0 until the mid-1970s, decreased to a record low of 1.26 in 2005 (see Figure 1.2). The rate has since increased slightly but has remained at a very low level – for example, 1.39 in 2010 and 1.46 in 2015. The population decline is being paralleled by a rapid increase in the proportion of older people in society. Japan became a ‘super-aged society’ in 2007, when the rate of those aged 65 or older in the total population exceeded 21 per cent. This figure is forecast to increase to as much as 36.1 per cent by 2040 and 39.9 per cent by 2060. The proportion of older people in Japan will remain the highest in the world.

Such demographic changes have major effects on transformations in the condition of the housing system. The government has traditionally encouraged the mass construction of dwellings to stimulate economic growth. Pressure from the demand for housing will be, however, significantly lessened in the future due to the shrinking and ageing population. It will thus become more difficult to maintain a high level of investment in housing production. If the number of households continues to increase with a decline in household size, it might be possible to sustain the high volume of housing construction despite the population decline. However, the number of households is also expected to start declining in the near future.

Figure 1.1 Population change in Japan (1990–2060)

Figure 1.2 Live births and total fertility rates in Japan (1947–2015)

In addition, the shift to post-growth society has been accompanied by a decline in the number of marriages and associated changes in household patterns. In post-war Japan, acquiring an owner-occupied house was closely linked with family formation (Hirayama and Izuhara, 2008). In some Western societies, not only married couples but also single people and cohabiting couples aspire to own a home, whereas in Japan most people do not purchase a dwelling until they get married. The government placed significance on encouraging marriage-based households to access home ownership in implementing housing policy, while the tax, social security and corporate-based welfare systems gave a range of financial advantages to conventional households. The combination of marriage and home ownership was indeed at the heart of Japan’s post-war social development. In other words, the decline in marriage has in turn meant a fundamental challenge to the post-war housing system based on ...