![]()

Part I

Preliminary reading of urban space

![]()

Chapter 1

Approaching a reading space

Urban space lies in between idea and reality, design concept and people’s lives, while simultaneously being embedded within the wider urban context, political, economic, and so on. According to Deleuze and Guattari (1994), architecture as a way of thinking crosses the boundaries of philosophy, science, and art. On the one hand, they consider art and simultaneously architecture as essentially concerned with creation of space experience and sensation (Nilsson, 2004). Architecture and art hence follow a pragmatic approach to ‘make space distinct … to determine its boundaries’, while philosophy and science are more concerned with understanding ‘the nature of space’ (Tschumi, 1975a: 29–30); while social studies are interested in the experience of people, body, and social in the urban space, both physical and phenomenological, through an empirical approach. This chapter reviews the reading(s) of space/place in philosophy, architecture, and social studies, and reflects on the need to develop an integrated reading of urban space.

Any study of place [urban space] also entails a bridging of interest across different academic paradigms, particularly … cultural studies and human-environment studies.

(Dovey, 2005: 16)

Accordingly, I shall trace the development of associated concepts and definitions of ‘space/place’ in philosophy, from the classic readings of chóra and topos, to the modern synonymous space and place respectively, as well as the emergent reversion to neo-chóra through Derrida’s deconstruction reading of space: ‘Khōra’. However, the latter part is discussed in Chapter 3. Consequently, this is complemented by an exploration of social studies of place, which shows a growing interest in the study of the relationship of people to place and attempts to integrate with architecture. Finally, this review investigates the similarities and consistencies between these readings, exploring the prospect of developing a primary framework for reading urban space through five different projections of space: Canter (empirical based, 1977a) and Relph (phenomenological, 1976) in social space; Markus (structuralist, 1980s~) and Tschumi (post-structuralist, 1980s~) in architectural space; and Canter’s facet theory of place (structuralist, 1997) integrating social and architectural space.

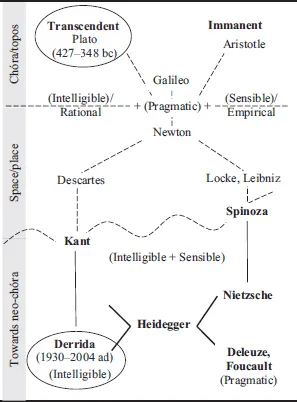

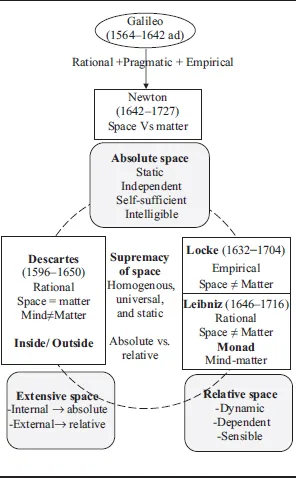

Space/place

In this section I attempt to explore the development of the concept of space/place in philosophy from the time of Plato’s chóra, the Timaeus (Plato, 1937 [360 BC]), towards the re-emergence of ‘neo-chóra’, ‘Khōra’ (Derrida, 1995). I hence adopt and develop Casey’s (1997a) classification of these concepts, which I outline as ‘chóra/topos’, ‘space/place’, and ‘towards chóra’. This classification is represented in Figure 1.1. The first phase, chóra/topos, draws a holistic approach to space/place developed by Plato’s chóra and Aristotle’s topos, ‘Physica’ (Aristotle, 1984 [350 BC]). Galileo then presents a transition to modern science and modern space (for further details see Galilei, 2008 [1615]). The second phase considers the modern concept space/place through the works of Newton, Descartes, Locke, Leibniz and reflects the duality between mind vs. matter, rational vs. empirical, absolute vs. relative space. Kant and Spinoza hence mark the transition between modern space and the third phase, towards chóra, the re-emerging interest in chóra and topos, where Kant and Heidegger attempt to reconcile the inherited duality of modern space. The third phase is developed through the works of Nietzsche, Foucault, and Deleuze on the one hand and Derrida on the other, as well as Heidegger. It is Derrida who brought back the concept of space/place to Plato’s chóra, through his deconstruction reading of space, ‘Khōra’.

Figure 1.1 Space/place in philosophy and science from Plato to Derrida

The representation of these concepts in Figure 1.1 is based on Agamben and Heller-Roazen’s (1999: 239) diagram, which considered the recent development of the concept of space/place, the third phase. Agamben and Heller-Roazen (1999) draw attention to the relationship between the transcendent, beyond or above the range of normal or physical ‘sensible’ human experience, and the immanent thinking, ‘operating from inside’ (Blackburn, 2008) – with Heidegger at the centre. In addition, I also examine Plato’s differentiation between intelligible/rational and sensible/empirical ways of thinking; see The Republic (Plato, 1892 [380 BC]), as well as pragmatic thinking emphasised by Galileo. The intelligible is ‘understood only by the intellect, not by the senses’, while the sensible is ‘done or chosen in accordance with … prudence [good sense]’, and the pragmatic is ‘dealing with things sensibly and realistically in a way that is based on practical rather than theoretical considerations’ (Stevenson, 2010). Finally, Derrida’s return to neo-Platonic chóra follows a transcendental rational thinking (Broadbent, 1991b). However, it is important to stress that I am not interested in the differentiation between space and place. Rather my interest is in the exploration of the concepts and themes developed relative to them. Accordingly, ‘space’ and ‘place’ are used as originally quoted by their authors, in order not to lose their intended meaning, or space/place is used as a general term. We shall hence review these three phases: chóra/topos, space/place, and towards chóra, whereas Derrida’s reading of Plato’s chóra, ‘Khōra’ is discussed in details in Chapter 3.

Chóra/topos

Chōra and topos were often used synonymously to refer to space and place.

(Rickert, 2007: 254)

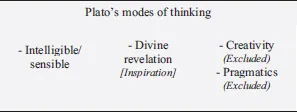

Broadbent (1990) reflects on the historic modes of thinking, Greek and Roman, Spanish, and Islamic. These modes constituted three basic ways of thinking: using pure geometric forms, a concern for the experience of human senses, and learning through trial and error. These approaches echo Plato’s (427–348 BC) modes of thinking the ‘intelligible, sensible and the intermediate’ (Launter, 2003: 84). Accordingly, Broadbent (1991b) discusses how the intelligible and the sensible have dominated western philosophy and metaphysics since Plato. Figure 1.2 illustrates these three modes of thinking and their association with the concepts of ‘chóra’ and ‘topos’.

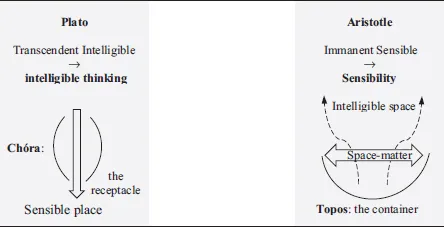

Plato and Aristotle approach the concepts of space/place through ‘chóra’ and ‘topos’ respectively. Plato acknowledges the dominance of intelligible chóra, space, whereas Aristotle subverts chóra, as part of sensible topos, place (Casey, 1997a). On the one hand, Plato differentiates between intelligible and sensible ways of thinking, where the intelligible logic is transcendent to and subverts the immanent sensibility (Kymalainen and Lehtinen, 2010; Launter, 2003; Plato, 1892 [380 BC]). This dominance helped to ignore the ‘world’ between them including pragmatism. Plato also included divine revelation as a mode of inspiration, which considers the ‘presence’ of God. But he ignored creativity, which relates to works of art, design … a world where ‘creative people literally “dream up” new, strange and wonderful idea[s]’. Creativity intrinsically challenges Plato’s intelligible world and was thus also excluded from his work (Broadbent, 1991b: 37); refer to Figure 1.3. Furthermore, the transcendent intelligible mode designates chóra as a receptacle that receives chaos and conceives order, geometry, and pure forms in particular. This order is thus superimposed on the sensible mode. The receptacle is also intrinsically independent from the properties of the sensible world (Casey, 1997a; Derrida, 1995; Grosz, 1995). I shall elaborate further on the idea of the ‘receptacle’ through the deconstruction reading of ‘chóra’ in Chapter 3.

Figure 1.2 A reading in ancient philosophy of space/place, chóra/topos

Figure 1.3 Plato’s world (after Broadbent, 1991a: 37)

On the other hand, Aristotle (384–322 BC), as the student of Plato, believed in the binary sensible/intelligible. However, he believed in the supremacy of sensible thinking (Broadbent, 1991b; see ‘sense and sensibilia’ in Aristotle, 1984 [350 BC]). He used a ‘logical system’, intelligible thinking, to explain his sensible observations of the world (Glusberg, 1991: 58; Tschumi, 1975a: 29). He approached place/space through the concept of space-matter, ‘topos’, a place which ‘subsumed chóra … as material [sensible] space’ as part of itself (Rickert, 2007: 253; Casey, 1997a). For Aristotle, place is dependent on the ‘matter’ contained, on their properties, volume, and boundaries which they exchange (Mendell, 1987). Accordingly, chóra loses her reciprocity as it attains the properties of matter and becomes the ‘container’ space instead of the ‘reciprocal’. Accordingly, place is a physical phenomenon shaped by immanent senses rather than a transcendent geometry. Aristotle thus followed an immanent sensible approach to read place as a ‘bounding container, the outer limit of the contained matter/body re-joining the inner limit of the containing place’ (Casey, 1997a: 58). The container space is defined as a setting ‘in which bodies [/matter] are located and move’ (McDonough, 2014). The latter view of immanent sensibility could reflect the production of creativity and internal inspiration, which was excluded by Plato. A construction of this reading of chóra, the receptacle and topos, the container is thus presented in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4 Chóra/topos: intelligible receptacle/sensible container

Subsequently, Galileo (1564–1642) brought back pragmatic thinking along with the sensible when he demonstrated the value of bringing ‘pragmatic experiment’ together with ‘intelligible thinking’ and ‘sensible observation’ rather than accepting the supremacy of the intelligible or sensible ways of thinking (Broadbent, 1991b; Pérez-Gómez, 1994). Accordingly, he launched the way to modern science and eventually to modern space.

Space/place

Such is modern space … not modern spaces. Modern space is ultimately one: … absolute, and infinite, homogenous and unitary, regular and striated, isotropic and isometric.

(Casey, 1997a: 193)

The intelligible, sensible, and pragmatic ways of thinking associated with chóra and topos were developed over centuries into coherent philosophies of rationalism: ‘reason rather than experience is the foundation of certainty in knowledge’; empiricism: ‘all knowledge is based on experience derived from the senses’; and pragmatism: that ‘evaluates theories or beliefs in terms of the success of their practical application’ respectively (Stevenson, 2010). Simultaneously, many of the early thinkers of space/place, like Newton (1642–1727), Descartes (1596–1650), Leibniz (1646–1716), and Spinoza (1632–1677), worked across both philosophy and science. Philosophy and science are both interested in the study of the nature of space. Philosophy considers the materialisation and production of concepts and notions of reality, while science deals with functions and relationships (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994). Accordingly, interpretations of the ‘nature of space’ in philosophy and science oscillate between space as ‘something subjective with which the mind categorizes things’, and space as ‘a material thing in which all material things are located’, respectively (Tschumi, 1975a: 29).

This duality in the way of thinking has dominated the understanding of space/place for a long time and helped the development of its ‘double identity’ between abstract and material: mind and matter. Furthermore, it prompted the separation between the container and the receptacle space, which were traditionally brought together through both Chóra and topos. Space, in general, is homogenous, static, and universal, and indifferent ‘to the specialness of place’. Place (topos) is considered a subset of this universal space (Casey, 1997a: 137, 133). I thus explore the reading of space/place through the ideas of Newton, Locke, Leibniz, and Descartes, which constitutes four notions of space: the absolute, the relativist, the relational, and the extensive respectively, see Figure 1.5. This reading reflects on the associated duality in between space and matter, and continues to highlight the introduction of the mind, the abstraction of space.

[Newton’s] space has an absolute existence over and above the spatial relations between objects.

(Okasha, 2002: 95)

Newton (1802) while following Galileo’s approach of involving pragmatic, intelligible, and sensible ways of thinking, adopted a rational absolute space (Casey, 1997a: 142; Glusberg, 1991). This absolute space ‘embraced the void’, ‘before any occupation by bodies [matter] or forces’ (Casey, 1997a: 139, 147). Accordingly, it broke the link in between Aristotle’s space-matter: space became detached from the properties and attributes of the inside material. Space is ‘an absolute container’ that consists of ‘determinate boundaries and/or dimensions’, which imply that matter is either inside or outside these boundaries (Pries, 2005; Weiss, 2005). This space is also static, whereas matter is mobile between absolute spaces. Consequently, Newton’s absolute space is rational, self-sufficient, independent, non-extensive, static and ‘immobile’: matter is either inside/outside space, and mobile from one static space to another (Casey, 1997a: 142).

Figure 1.5 A reading of Descartes, Locke, and Leibniz on space/place, matter, and mind

Our idea of Place is nothing else, but such a relative position of anything.

(Locke, 1975 [1696]: 101)

By contrast, Locke (1975 [1696]) adopted a ‘relative space’, which is ‘a movable dimension … of the absolute space it occupies’ (Casey, 1997a: 143). He thus ‘reasserted the precedence of the senses’ through space dependence on sensible relations (Broadbent, 1991b: 40). Simultaneously, he considers space and matter as two separate entities though space is dependent on matter. Relative space is also reduced to a Cartesian ...