![]()

1 Poisons in the historic medicine cabinet

Toine Pieters

Suppose that you are stricken with bad luck and you are diagnosed with cancer.1 About half of all men and a third of all women will be diagnosed with cancer at some point in their lives. In the process, your doctor will tell you about your cancer: the name, size, location, origin, whether it has spread and if it is slow-growing or aggressive. You will certainly ask your doctor about the available treatment options, the success rates and the expected side effects. You will learn that the benefits associated with cancer treatments in terms of survival rates do not come without risk. Most cancer treatments are fraught with iatrogenic harm. High risk/benefit ratios have been integral to the culture of cancer treatment for more than a century.2 Severe side effects from drugs that are considered poisonous outside of the hospital ward have become an accepted part of life in most cancer treatment centres. The treatment-related morbidity and mortality rates due to cardio- or nephrotoxicity are rather high.3 Your cancer specialist, trained in healing but frequently frustrated by being unable to deliver a cure, will be prepared to go to any extreme (overdosing and over-drugging) if you allow it. At the same time, you, like most other patients, in a desperate effort to avert a presumed ‘death sentence’, will be willing to try almost anything hoping for a cure or at least postponing death, thus placing treatment side effects and iatrogenic harm second to potential benefits. Suppose that the doctor and you decide in favour of chemotherapy, you might experience a highly toxic fluid being injected into your veins. The nurse administering it will be wearing protective gloves because the drug could burn his/her skin if even a tiny drop is spilled. You can’t help asking yourself, ‘If such precautions are needed to be taken on the outside, what is this drug doing to me on the inside?’ During your treatment, you might lose your hair by the handful, appetite, weight, skin colour and zest for life.

The aforementioned drastic 21st-century interventionist therapy is practised on a regular basis in cancer clinics around the globe and is as much part of the history of pharmacology and toxicology as the heroic medicine practised in the 18th and 19th centuries. This also applies to early modern last-ditch efforts to save the lives of patients suffering from venereal and other infectious diseases. Historically, European and North American pharmacopoeias included a considerable number of drugs that we now consider poisons. For example, mercury in ointments for the treatment of syphilis or in calomel for intestinal purging, strychnine and arsenic salts as ingredients for tonic medicines, opium to relieve severe pains and tartar emetic for vomiting. Most of these substances were (re)introduced into Western medicine by the renowned 16th-century physician and alchemist Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (1493–1541), who took the name Paracelsus. In his writings, Paracelsus persistently addressed the question: What is a poison?

The word poison, as we know it, refers to a substance that is harmful or lethal to a living organism.4 Generally, it is associated with something that harms a person or thing. However, informally, it can be used to signify a drink such as ‘What is your poison?’ In that sense, poison is etymologically linked to the Latin words potio and poto (to drink). In Roman and Greek culture, poisons were often prepared in the form of a drinkable concoction that could be used for a state-ordered suicide as for instance in the case of the Greek philosopher Socrates (469–399 bc). It is worth mentioning that in modern Greek, the word farmaki is used informally to refer to a poisonous substance. This brings us to the ambiguous and complex ancient Greek word ‘pharmakon’, meaning sacrament, spell-giving potion, remedy, poison, talisman, perfume, cosmetic or intoxicant.5 Thus, the word poison was used to signify both the healing and useful effects as well as the damaging effects of a pharmacon. Paracelsus skilfully exploited this ambiguity by developing the following astute concept of what constitutes the difference between a poisonous and a non-poisonous substance:6

The famous English physician, toxicologist and ‘father’ of British forensic medicine, Alfred Swaine Taylor (1806–1880), pragmatically paraphrased Paracelsus by arguing that ‘a poison in a small dose is a medicine, and a medicine in a larger dose is a poison’.7 Whether indeed the dose should be considered the single determinant of the poisonous or therapeutic quality of a substance will be up for discussion in this chapter.

The ‘Paracelsus principle’ of dose and response may be an important conceptual legacy, but in terms of a material and poisonous legacy, Paracelsus had a far greater impact on the history of medicine and toxicology. Inspired by Rhazes’ Liber Secretorum, Paracelsus reintroduced a number of potent substances to the materia medica. Mercury, antimony and arsenic would develop into major commodities with a far-reaching impact on medicine, society and environment. For those historians who love to literally dig into the history of poisons, the riverbeds are a historical treasure and can be read as a cross section of poisonous compounds from arsenic and mercury compounds up to barbiturates and modern-day cytotoxic drugs.8 In this chapter, I will historically analyse the multidimensional and dynamic role of drugs as poisons and vice versa, shedding light on prototypical trajectories of medical, criminal and social poisoning from the early modern period (15th century) to the current era of modern scientific medicine.

The history of the ‘king of poisons’ with a Dutch touch

John Parascandola, a historian of pharmacy, crowned arsenic as the ‘king of poisons’.9 And indeed, there is hardly any other poison with a longer, darker, more pervasive historical trajectory than arsenic. From the 15th century onwards, arsenical poisons, publicly known as poudres de succession, would become increasingly popular as a method of political assassination and homicide. The most notorious families associated with historical arsenic poisonings are the Borgias and the Medici, but they should really be considered as pioneers who prepared the way, along with Paracelsus, for exponentially growing silent crowds of criminal, iatrogenic and environmental arsenic poisonings.

Efforts to control the availability of arsenic date back to the late 15th century when city authorities across Europe began worrying about the growing and unrestricted sale of poisonous drugs and their focus was on arsenic. The ‘king of poisons’ became widely regarded as a social poison with the potential to undermine social cohesion in towns and kingdoms. Over time, tighter poison control regimes were put in place. The professional boundaries in the medical marketplace were still fluid with overlap between physic, surgery and pharmacy. Physicians, surgeons and apothecaries were all involved in the testing, preparation and assessment of drugs, poisons and antidotes to some degree.10 Antidotes such as antidotum arcenici or hydrargyrosus in the form of a chelating agent were widely used. Dating back to the days of Pedanius Dioscorides (40–90), it was also standard practice to use emetics to treat poisoning. It was assumed that clearing the stomach would eliminate any ingested poison from the body. But, medical history shows that the heroic emesis therapy was far from harmless and frequently induced iatrogenic damage.

From the 16th century onwards, apothecaries were regarded as the most trustful gatekeepers for the sale of toxic medicinal substances. For example, in 1687, the city council of the Dutch city of Leiden curbed the free sale of arsenic powder or what was known as ‘rats herb’ and passed legislation restricting sales to only those by the town’s official pharmacist.11 Rotterdam, Amsterdam and Haarlem soon followed suit.12 Although there is little reason to suppose that these town-restricted arsenic acts exerted a significant influence on the overall incidence of poisoning, with druggists still selling significant quantities of rat herb, nevertheless it gradually paved the way for the establishment of pharmacy-centred poison legislation across Europe.

According to Parascandola, arsenic poisoning reached a peak in the 1850s when the use of arsenic compounds exploded in the home, on the farm and in various industries.13 A wide array of goods contained arsenic including clothes, soap, books, paint, wallpaper, glass and glassware, and popular patent medicines like the tonic Fowler’s solution. It is not surprising that given arsenic’s routine presence in everyday life and environmental accumulation, a rapidly growing number of people suffered from unintentional poisoning at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Fatalities due to chronic arsenic exposure were most likely far higher than the numbers involved in homicides and the new wave of mariticidal poisonings in attempts to cash in on life-insurance policies. In widely published French criminal records, statistics from 1835 to 1885 for arsenic poisonings figure prominently as 836 out of 1,759 cases.14 The number of poisoning cases reported was no doubt lower than the actual number of cases, but the introduction of chemical tests made it harder for murderers to get away with their crimes. The development of analytical methods to detect and quantify poisonous chemicals like arsenic (e.g. the Marsh and the Reinsch tests) set the stage for a new field of science, forensics, that would be called upon in court trials and for legally enforced national restrictions on the sale of arsenic and other poisons.15 Inquests and trials involving suspected and subsequently scientifically confirmed arsenic poisoning had high public visibility throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th century. One example is the Dutch trial of Maria Catharina van der Linden-Swanenburg (1839–1915), known as the ‘Leiden poisoner Mie’. Her serial murder cases using arsenic can be found in the Guinness Book of Records.16

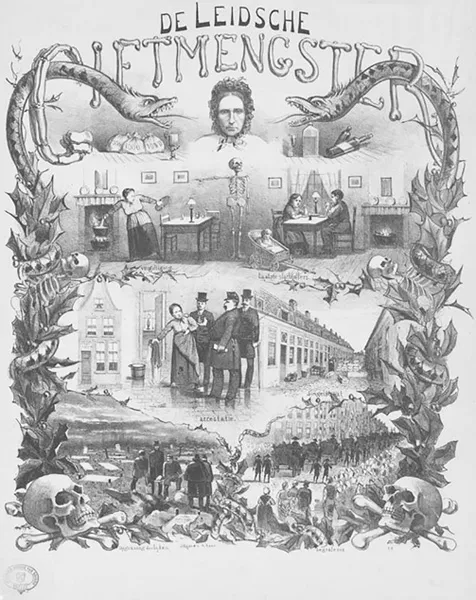

In approximately 1879, murderous Mie began the systematic poisoning of poor local residents in the town of Leiden. Because of her great helpfulness, she was nicknamed ‘Good Mie’, and she established a large circle of neighbours, relatives and friends. As a dear and helpful friend, she was allowed to walk into people’s houses on a regular basis. No one associated her with the rather frequent regrettable deaths and illnesses that occurred among her circle of friends, since the 19th century was known for its high burden of disease and mortality. Therefore, no particular event stood out. It even remained unnoticed that Good Mie had advised all her acquaintances to buy funeral insurance from various burial funds (and if necessary, Good Mie solicited funeral insurance for others and paid the membership fee of 7.5 cents per week herself). The practice of purchasing funeral insurance for someone else without consent was not prohibited in the 19th century. Good Mie poisoned her insured loved ones with an anti-bed bug preparation, which contained one part of sulphur and four parts of arsenic, bought from the druggist and subsequently sprinkled in coffee, milk or pea soup. In total, Good Mie poisoned 102 people, of whom 27 died and 45 suffered from severe intestinal organ damage. After the victims’ burial, she collected their insurance money, which was usually 50 guilders. She even poisoned her own parents, sister, brother-in-law and their children. In the end, the family killings raised the family doctor’s suspicion and he sounded the alarm in 1883. Good Mie was imprisoned and brought to trial. The examining judge ordered the exhumation of the corpses at the graveyard and sent them for forensic laboratory examination. The presence of arsenic was indeed confirmed, and Good Mie’s verdict in 1885 was life imprisonment.17 The court trial attracted national and international attention in the news media. Good Mie’s serial poisonings stirred imaginations that had been fed by arsenic’s prominent role in 19th-century literary works from pulp fiction to classical literature. Most certainly, the best-known novel in which arsenic played a dark role was Gustav Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. Iconography of the two magically potent snakes in a fatal stranglehold of the root of the tree of life used during the trial of murderous Mie and again in stage plays (see Figure 1.1) is most telling. Of course, the omnipotent presence of scientific evidence leaves no room for Good Mie’s lucky escape.

Figure 1.1 A 1883 lithograph of the life of ‘murderous Mie’ by R. Raar, Leiden University Library.

Handling God’s own medicine

The heroic remedy and poisonous plant medicine with the longest history of use and abuse that is still used today is opium.18 The wo...