![]()

1 Getting acquainted

1.1 What exactly is a viol?

At first glance this looks like the sort of quite banal but nonetheless thoroughly justified question that can be readily dispatched in just a few crisp sentences. Let us begin therefore by saying that the viol, also known as the viola da gamba (or just gamba), is a bowed stringed instrument with six strings tuned at intervals of a fourth, a fourth, a third, a fourth and a fourth, with a fretted neck. Its body differs from that of the violin family in that it has sloping shoulders, C-shaped soundholes, less sharply tapering middle bouts, and a flat back ending in a tilted peg-box. The back and the soundboard do not overhang the ribs. Players hold the instrument vertically and support it with their legs. The bow is held with an underhand grip.

If you like your descriptions short and sweet then no doubt you will be perfectly satisfied with what you have just read. Unfortunately, the products of human ingenuity can rarely be encapsulated in a few short and simple phrases, and the viol seems to show particular agility in escaping simplifications of this kind. It is therefore not without some regret that we are forced to admit that only an annoyingly small part of the above description can be universally applied to the viol.

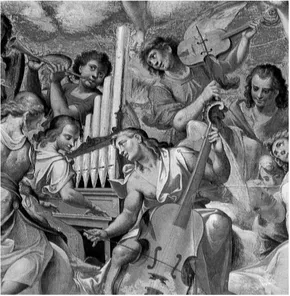

Let us start with the external form of the instrument. It is certainly true that the characteristic body-shape we have just described eventually prevailed during the Baroque era, but what an amazing richness of stylistic development and experimentation it went through to reach that stage! If we look at examples from the Renaissance we find not only rounded shoulders sloping at every conceivable angle but, just as often, square shoulders formed at 90 degrees or even at acute angles. Waists can end in sharp edges, as with the violin (Figure 1), or can be rounded like that of a guitar, while the extravagant festoon-shapes of some viols bear testimony to the whimsical imaginations of their makers. Backs are not always flat, and often both the back and the soundboard overhang the ribs. The C-shaped soundholes can face either inwards or outwards, and sometimes have small notches in the middle that make them look like moustaches. We also find soundholes shaped like the letter f or in the form of teardrops, dolphins or flames. Some viols also have a rose located near the fretboard. But the fatal blow to our attempts at neat organological categorisation is dealt by viols that outwardly display all the characteristics of the violin family. We find viols of this kind not only in paintings of the (organologically speaking) notoriously fluid Renaissance (Figure 1) – and not just in the work of artists regarding whom we can state that they had no specialist knowledge of musical instruments – but also in a respected tutor-book such as that published by Christopher Simpson in 1659 (Figure 5). So where exactly do we draw the line between the two great families of stringed instruments? What are the special characteristics that make a viol what it is? This question will continue to exercise us, but here, for the time being, we can leave it unanswered.

Figure 1 Aurelio Luini and Carlo Urbino, Assunzione della Vergine, 1576, detail. Verbania-Pallanza, Church of the Madonna di Campagna. Viol with six strings, frets and underhand bow-grip, but with a cello-shaped body.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Madonna_di_Campagna_-_Fresco_2_Apsis.webp

Author Wolfgang Sauber.

The statement we made above about the number of strings is just as open to challenge as all the others, since five or seven strings and not six were normal for the viol at various times and places. Very occasionally we even read of eight-stringed instruments, and in 18th-century France a four-stringed instrument called the pardessus de viole managed to sneak its way into the viol family. There were even exceptions to the standard 4-4-3-4-4 tuning, the interval of a third sometimes being allocated to higher or lower strings or even omitted altogether in tunings made up exclusively of fourths or of fourths and fifths, not to mention the numerous scordatura tunings, especially those associated with the English lyra viol.

As for the playing position, the viol’s alternative name of viola da gamba (i.e. ‘leg viol’) should at least provide us with a measure of certainty: this was obviously an instrument intended to be played vertically and never resting on the arm or shoulder. This does not, however, mean that it was always held between the player’s legs. In old canvases we sometimes see the viol being played resting on the ground or a stool or being held across the player’s lap like a guitar or, very exceptionally, suspended from the player’s shoulders by a strap, in which case the player had a choice of sitting or standing. These are certainly exceptions, and they might be influenced more by iconological considerations than questions of instrumental technique, but even so they are part of the history of the instrument. Regarding the bow, this can be held underhand, but it can also be held edgeways behind the frog. References to the bow being held with an overhand grip like that used for the violin are, however, exceptionally rare. We should nonetheless note that neither the underhand grip nor the vertical playing position are in any way exclusive to the viol, as both are shared with the bass instruments of the violin family.

There is, however, one feature that is common to all viols: small, easily worn-out and often only sketchily represented by artists though they might be, they are still of decisive importance for the technical character of the instrument: we are, of course, talking about frets. Their presence ensures the viol an intermediate position between the bowed and plucked instruments and highlights its relationship with the lute. From a technical perspective, frets make it easier to play chords. The viol usually has seven frets a semitone apart, covering a fifth between them, but here again there is no shortage of exceptions, e.g. the eighth fret at an octave interval which Christopher Simpson recommended for his highly virtuosic improvisations in the division viol.

To sum up, only two characteristics are common to all viols of all periods: the playing position and the frets. This is certainly rather disconcerting if our goal is to achieve a precise scientific classification, but in no way did the viol’s contemporaries find the instrument obscure or baffling. It was a well-known and readily recognised instrument, and neither musicians nor the general public needed any elaborate explanations to make sense of it. Therefore, instead of wasting time searching for a generally applicable definition of the viol we should be content to note that it was a widely played and versatile instrument which, during the three centuries or so of its history, adapted swiftly and flexibly to musical change and innovation.

There is, however, one characteristic of the instrument that we cannot omit from this initial portrait even if, from an organological perspective, it is not a tangible one: the viol was always associated with the upper echelons of society. It was the aristocratic instrument par excellence. “We call viols those instruments with which the aristocracy, merchants and other people of quality pass their time”1 wrote Philibert Jambe de Fer in 1556, and for him this was obviously a perfectly adequate definition of the instrument which needed no further elucidation. In 1570, Benedetto Varchi compared the viol with the high dramatic style, in contrast to the light lyrical style which he assigned to the violin: “Personally I’d rather be a good dramatist than an outstanding lyric poet, for who wouldn’t prefer to play the viol moderately well than fiddle around flawlessly on a rebec?”2 And as late as 1789 the music historian Charles Burney could write: “During the last century [the viol] was a necessary appendage to a nobleman or gentleman’s family throughout Europe”.3 The violin, in contrast, stood a long way below the viol in the social scale. As Boccalini wrote at the beginning of the 17th century, the violin had “only recently been wrested from those ignorant bands in which certain vulgar performers wend their rascally way through the meanest of taverns”.4

1.2 What is the viol called?

The normalising tendency of the 20th century has assigned to the revived viol a set of unequivocal names that leave no room for misunderstanding: the Italians unhesitatingly refer to it as the viola da gamba, the English as the viol, the French as the viole de gambe, German-speakers as the Gambe and so on. But if we look back at the course of history we find that the situation has not always been so crystal-clear. Devotees of unimpeachable definitions will be forced to admit with dismay that our instrument has never had its own unique name. The greatest fluctuations in nomenclature predictably occurred during the Renaissance – that youthfully inspired and efferv...