![]()

1

Origins and history

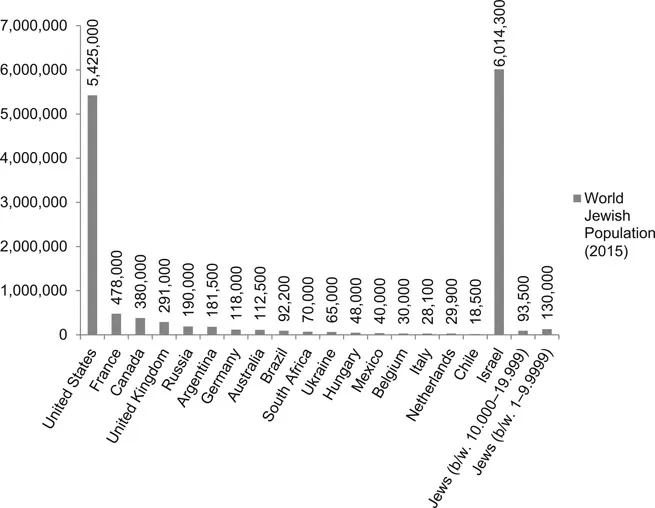

According to a report issued by American Jewish Year Book, the estimated world Jewish population was 14,310,500 at the beginning of 2015. The Jewish populations of Israel and the United States together constitute more than 82 percent of the total. Of this, more than 50 percent of Jews are concentrated in these five metropolitan areas: Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Haifa, New York and Los Angeles. Another 16 countries each have more than 18,000 Jews.1 Due to the fact that the Jewish population of Turkey is less than 18,000, Turkey’s Jews are not included in Figure 1.1.

Many scholars who studied the concept of diaspora have agreed on the definition of the term as the dispersal of a people from its original homeland, specifically the Jews. Historically Jews were exiled from their homeland through the destruction of their temples and by the plundering of their holy city, Jerusalem.2 The term now encompasses a broad range of groups beyond the Jews, such as refugees, labor workers and Roma.

Accordingly Jewish migration, due to forced exiles and dispersions, led to Jewish population in different parts of the world. Jews ended up living in many different countries. Historically it is accepted that the deportation of Jews from the Holy Land by the Assyrian King of Jews made Jews the first diaspora community.3 Over time they grew and embraced many different ethnic and linguistic groupings and different cultural richness in their resettled new lands.4 These scattered Jewish communities borrowed customs and culture from their non-Jewish neighbor societies and countries while continuing to preserve their essential traditions based on the sacred texts.5 While these different customs and cultures distinguished Jewish communities from one another, their common Jewish religion and a history of shared past and destiny acted like strong cement binding them to other Jews.6

It is very difficult to give one definition of Judaism that would be universally acceptable. As Martin Sicker points out, modern times have produced several Jewish schools of religious thought that established “contemporary Judaism” such as Orthodox, Conservative, Reformist and Reconstructionist.7 In this study, Judaism is understood as Sicker describes it

the framework that encompasses the central religious beliefs and values that most of the Jewish people have considered normative from antiquity to modern times which can be referred to as “traditional Judaism” to make a distinction between the other schools of religious thought.

Figure 1.1 World Jewish Population

In addition, while Judaism refers to a religious value system, the term “Jewish” also means a national or ethnic identity. Thus, according to Sicker, while Theodor Herzl, Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein can be characterized as “Jewish thinkers”, they cannot be called “Judaic thinkers” since their ideas and notions are not derived from the sources of traditional Judaism.8 Jacob Neusner explained this simply as “all those who practice the religion, Judaism, by the definition of Judaism fall into the ethnic group, the Jews, but not all members of the ethnic group, the Jews, practice Judaism”.9 Additionally, to him, because it also accepts conversions, Judaism cannot be seen solely as an ethnic religion.10 Following that he states,

but a religion more than its creed interpreted through liturgy that we cannot conceive the faith as a set of discrete notions that separated from the life of people who refer to those notions. The Jews as an ethnic group, wherever they resided, shapes issues facing Judaism, the religion.11

To better illustrate, Neusner cites the Holocaust as an example. He wrote that the Holocaust was a “demographic catastrophe” for the Jewish nation. As a consequence of this, Judaism faced a “principal theological dilemma” in the twentieth century and beyond.12 The demographic decline of the Jews also had influences on the life of the synagogue as well, so he concluded “we cannot draw too rigid distinction between ethnic and the religious in the context of the Jewish people and Judaism”.13

Hence, a definition of who is a Jew needs discussion and clarification. However, the perception of Jewishness as both a religion and ethnicity and the “distinctive social stratification” of Jews have made this task difficult.14 According to the halakhic criteria, the Jewish law, a Jew is defined as “who is born of a Jewish mother or who has converted to Orthodox Judaism” which is also followed by Conservative and Orthodox Judaism.15 In Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism; “a Jew is a person born of a Jewish mother or of a Jewish father or who has converted to Judaism”.16 As seen, status is gained through birth or by conversion, which represents the “melding of the ethnic and genealogical with the religious and theological”. Thus, there is no clear-cut distinction to separate the ethnic from the religious since the word Jew and Jewish stress “the ethnic character of the Jews as a group”.17

Abraham Malamat claimed that the history of the Jews cannot be narrowed down to the boundaries of Palestine solely but was also tied to the ancient Near Eastern lands including Mesopotamia, “land of the Hebrew’s origin” and the land of Nile, Egypt, a flourishing refuge for Jews.18

In the earliest time of Jewish history the people were exposed to two dreadful incidents destruction and exile. These are, first, the exile of “ten tribes” of Israel by the Assyrian King and the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE by the Babylonians.19 Afterwards, as Hayim Tadmor pointed out, Jewish history adopted a new pattern as “a vital diaspora coexisting in a symbiotic relationship with the community in the homeland”.20 With the destruction of the Second Temple by the Roman Empire in 70 CE, the expulsion and political and religious oppression, in addition to the economic bonanza of wealthy countries, made a huge influence on the demographic expansion of Jewish Diaspora. The political, social and economic conditions of the Jewish Diaspora varied according to the country in which they lived. Nevertheless, the common destiny of the Jewish nation, despite being dispersed in different parts of the world, was “closely united”, and any serious limits on religious freedom had an effect among other Jewish communities.21 Jews of the diaspora always kept strong ties with the Land of Israel.

After the fall of the temples, an extensive period of proselytism occurred.22 According to Safrai, the majority of the proselytes we...