![]()

1Unsustainability as a problem of political economy

Politicizing the Anthropocene, politicizing decarbonization

As hinted in the introduction to this book, many ways of understanding sustainability and unsustainability are deeply technocratic and depoliticizing. This has been long understood by many but is an important point of departure for thinking about the problem as a political-economic one. Our main aim in this book is to show the importance of ecology to IPE, but one way of thinking about this is to show the importance of IPE to understanding environmental politics. Two recent manifestations of this way of approaching the subject can be seen in recent debates – about the ‘Anthropocene’ on the one hand, and about ‘decarbonization’ on the other, and so we introduce the main themes of this chapter by taking a closer look at these two concepts.

The Anthropocene is a concept popularized by the Nobel Prize-winning atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen in the early 2000s (Crutzen 2002). As Zalasiewicz et al. (2011) note, the term ‘Anthropozoic’ was coined by Italian geologist Antonio Stoppani in the 1870s, and Crutzen resurrected the term by arguing that humans had ushered in a new period of geological time. It entails the claim that humans have become in effect a key driver of biophysical and geological processes – the Anthropocene is thus understood as a geological epoch to succeed the Holocene within which human civilizations emerged. The Holocene began some 11,500 years ago, and as Zalasiewicz et al. (2011, 837) note, ‘many of the surface bodies of sediment on which we live – the soils, river deposits, deltas, coastal plains and so on – were formed during this time’. Basic planetary cycles – of water, carbon, nitrogen, notably – are now ones where human activities play a defining role in shaping their patterns. And basic life conditions – the acidity of oceans, the temperature of the air, rainfall patterns, the condition of soil, the sedimentation of rivers and estuaries, the number and reach of forested areas, the extent of glaciers and sea ice, etc. – are now heavily shaped by human activities (Zalasiewicz et al. 2011). In fact, human activity has even been implicated in the slowing of the Earth’s rotation (a side-effect of rising sea levels; see Mitrovica et al. 2015)!

Meanwhile, ‘decarbonization’ has become a powerful frame, driving responses to the Anthropocene and specifically climate change. In June 2015, for instance, the leaders of the G7 pledged to completely phase out the use of fossil fuels by the end of the twenty-first century (Connolly 2015). The idea of taking the carbon out of the global economy has enabled businesses, politicians, bureaucrats and social movement activists alike to open up a space to think about a global economy beyond fossil fuels, and thus to minimize the risks of global climate change, perhaps the most important single systemic evidence of the unsustainability of our current world.

However, as commonly expressed, both the frames of the Anthropocene and decarbonization, important though they are, tend to fall into a couple of interrelated traps that have the cumulative effect of depoliticizing the question of unsustainability. First, they often situate the problem as one of technological development and implementation; that it is particular technologies used by humans, notably those that depend on fossil fuel consumption, that need to be radically changed, as opposed to broader forms of human organization, which would raise questions about the overall sustainability of high rates of consumption. This can be seen in statements by influential groups such as the ‘eco-modernists’ associated with the Breakthrough Institute in the US, for instance:

We write with the conviction that knowledge and technology, applied with wisdom, might allow for a good, or even great, Anthropocene. A good Anthropocene demands that humans use their growing social, economic, and technological powers to make life better for people, stabilize the climate, and protect the natural world.

(Asafu-Adjaye et al. 2015)

Second, the dominant framing tends to pose the question as one of an undifferentiated humanity: in the Anthropocene it is the ‘anthropos’ – humanity – which is changing the world, and on whom those changes impose their worrying effects. This avoids mention of the great variety of forms of social organization to be found within humanity, each of which has its own specific set of ecological effects. Via both of these ways of thinking, mainstream approaches to the Anthropocene and decarbonization thus have the effect of depoliticizing the question of unsustainability in the sense that they abstract it from questions of power, wealth, authority, conflict, and legitimacy that are both central to understanding political economy but also central to many of the dynamics of unsustainability. In doing this, they close down space for thinking adequately about the multidimensional challenges involved in genuine sustainability.

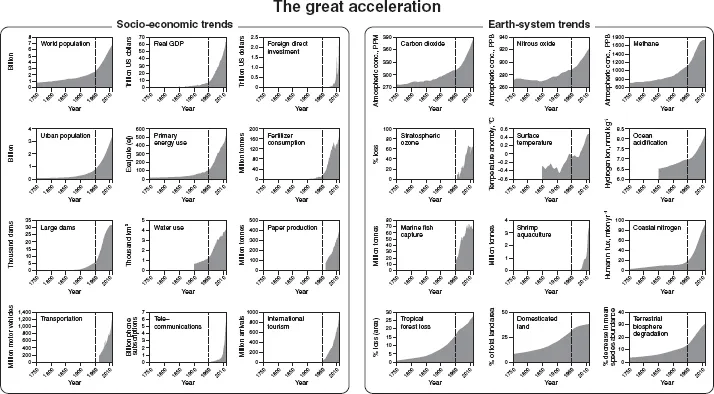

In the notion of the Anthropocene, for example, there is a debate about when it emerged. Various candidates exist, from the emergence of agriculture (and related accelerations in deforestation, mining, transportation, and reworking of waterways: see for example Ruddiman 2003; Syvitski and Kettner 2011) onwards to the modern era. Two key moments identified from the latter are commonly asserted; one is the Industrial Revolution, understood principally as a shift from renewable sources of energy (animals including humans, wood, water, wind) to non-renewable ones (coal, principally, and later oil and gas), which had a recognizable imprint on the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide (Pachauri and Reisinger 2007). And another is what is referred to as the ‘Great Acceleration’, a jump shift in the consumption of these non-renewable energy resources that occurred from World War Two (WWII) onwards (Steffen et al. 2015). This is the trigger also for a similar acceleration in carbon dioxide emissions, and thus the moment that significant climate change becomes inevitable (see Figure 1.1).

For both of these candidates, however, the challenges identified above are evident. The ‘problem’ appears to be the shift in technologies that humans use from the late eighteenth century onwards, and then accelerate (and diversify, from coal to oil and gas as well) in the mid-twentieth century. These are understood as quantitative and qualitative shifts in the sorts of effects ‘humans’ in their entirety impose on ‘nature’ in its entirety, via the medium of the ‘choice’ of technology. The scare quotes are deliberate, indicating the particular problems involved in this set of claims. For it is demonstrably not ‘humans’ as a whole, but rather particular forms of human society, with their identifiable forms of social organization and stratification, that causally generate both the Industrial Revolution and the great acceleration. Consider, for instance, the ‘socio-economic’ indicators on the left side of Figure 1.1. We must ask ourselves whether such trends are merely a manifestation of ‘human nature’ and the ‘natural’ growth of the world population of humans (as the figure implies), or if there is something within the structural dynamics underpinning the post-war global political economy which facilitated a ‘great acceleration’ in areas such as urbanization, fertilizer consumption, energy and water use, transportation, etc. We submit that ‘nature’ does not exist as an undifferentiated space separate from human societies, but rather is itself highly diverse and always co-evolving with humans (as others have pointed out; see for instance Castree and Braun 2001). In this sense technologies are not ‘chosen’ by societies in any meaningful sense, but rather emerge and evolve out of specific innovations by particular groups of people, always in the context of pre-existing and particular political-economic settings, and for specific purposes.

The Industrial Revolution occurred specifically within the forms of capitalist social relations that had emerged in North-Western Europe, especially England, in the seventeenth century. This entailed the shift in social production relations from ties of feudal obligation between lord and peasant farmer to those between capitalist landlord and ‘free’ farm labourer who was paid a wage for his or her work instead of owing a percentage of their harvest. This change in the relations of production shifted the incentives for the dominant class, making them see labour as a cost which had to be minimized rather than an asset to be expanded, and thus generated a core dynamic of technological innovation central to capitalism. Such changes also entailed the progressive rise of towns and cities, and thus the ‘bourgeoisie’ as an urban, commercial class, seeking to free itself from the constraints on commerce imposed by previous feudal norms. This political struggle produced many of the central shifts in the organization of state power – through the emergence of modern representative institutions and the decline of monarchic and aristocratic power, the rule of law, and property relations, notably. The Industrial Revolution was thus made possible by the combination of these forces, as constraints on urban commercial activity were removed politically just as large numbers of people were forced off the land and became a labour force for the bourgeoisie to employ.

Figure 1.1The great acceleration.

Source: redrawn on the basis of Steffen W.W. Broadgate, L. Deutch, O. and C. Ludwig (2015), The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. The Anthropocene Review.

The interplay between class conflict (both capitalist-worker and capitalist-aristocrat), technological innovation, and political authority is central to the origins of the Industrial Revolution and thus to the socio-ecological transformation involved in the shift in energy use identified by those referring to the Anthropocene (Malm 2015). Those developing the novel technologies that were central to this shift were responding to the basic incentives for technological innovation entailed in capitalism, as well as the availability of labour and finance enabled by the shifts in social relations and the political struggles of the bourgeoisie (Harvey 2010). These were notably the coal-fired steam engine that revolutionized manufacturing and the railways and shipping lines that revolutionized transport. The mechanization of transport it entailed is obvious. But the railways also accelerated other sorts of socio-ecological shifts. Notably, the extension of the railways into rural areas in England and elsewhere lead to a significant decline in the use of wood as a domestic fuel, since coal became available for domestic heating, saving workers a considerable amount of time and work for heating subsistence, freeing them up for commercial activity, while causing the decline in coppicing and thus triggering reforestation processes, in England at least (see especially Rackham 2000).

Political-economic contexts are similarly crucial to understanding the great acceleration. By the 1950s, capitalist relations and dynamics had become largely globalized, and helped engender geopolitical competition between competing states. Already by World War One (WWI), a decisive shift towards oil had been taken as the world’s leading navies (American and British, in particular) made the shift from coal to petroleum-based propulsion systems (Podobnik 1999, 160). This shift facilitated the strategic political importance of the Middle East and many of the conflicts that have centred on that region since (Klare 2001). WWII entrenched the oil-centred global economy we still have, with tanks, planes and rockets central to the pursuit of warfare, but also through the extraction, processing and transport of resources and ‘value-added’ products central to expanding the gross domestic product (GDP) and a positive trade balance.

At the same time, however, WWII created two crucially important social and political changes. First, it further empowered trade unions and other worker organizations within the political system as they became central to the success of the war effort. These political changes cemented shifts in political economy which had emerged earlier in the US (through the New Deal) and some European countries in the 1930s, and produced the ‘post war consensus’ around Keynesian economic management, an expansive welfare state, and embedded at the international level in multilateral economic institutions that sought to stabilize and promote global economic integration. This served as the foundation for what in French is called Les Trente Glorieuses (Fourastié 1979) – a 30-year period (1945–1975) of relatively stable economic expansion unprecedented in Western history, which, of course, serves as the political-economic setting for the acceleration in the use of oil and, increasingly, natural gas, that Anthropocene writers identify. Cold War geopolitics served as an additional influencing force here, as Western political leaders attempted to placate working-class organizations to undermine the ‘Communist Threat’. Further, the Cold War also created its own dynamics favouring the great acceleration, with military development being important to the expansion of energy use in both the East and the West.

Second, WWII produced the pressures for decolonization and over the subsequent two decades the abandonment of formal European empires in Africa, the Caribbean, and South and Southeast Asia. Associated with this was thus the invention of ‘development’ as an object or project to create the sorts of industrialization in ex-colonies that had occurred in the West in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Escobar 1995). While Southern countries remained largely exporters of raw materials to the Global North, development as a project nevertheless contributed to the great acceleration, and perhaps more recently has become increasingly central to its continuation, as the continued exponential growth in fossil fuel use and carbon dioxide emissions is now driven by growth in countries like China and India, which produce a significant share of the world’s manufactured goods. According to The Economist, China alone produces around one-quarter of the world’s entire manufacturing output (by value). It adds that ‘China produces about 80% of the world’s air-conditioners, 70% of its mobile phones and 60% of its shoes’ (The Economist 2015).

We thus need concepts central to political economy to understand the problem of unsustainability, since the typical framing of unsustainability as a problem of technological choice by an undifferentiated humanity is inadequate. We do not claim here to be the first to assert this. There are many similar responses to debates about the Anthropocene on which we seek here to build. For example, Moore (2015) has suggested the Anthropocene be referred to more adequately as the ‘Capitalocene’ – that it is precisely capitalism that has engendered the sorts of radical shifts in energy sources and expansion in their use that has had such radical effects on the biophysical character of the planet. Others (notably Bellamy Foster 1999; Clark and York 2005) draw on Marx’s notion of ‘metabolism’ to describe a ‘metabolic rift’...