eBook - ePub

New Approaches to Cinematic Space

This is a test

- 254 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Approaches to Cinematic Space

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

New Approaches to Cinematic Space aims to discuss the process of creation of cinematic spaces through moving images and the subsequent interpretation of their purpose and meaning. Throughout seventeen chapters, this edited collection will attempt to identify and interpret the formal strategies used by different filmmakers to depict real or imaginary places and turn them into abstract, conceptual spaces. The contributors to this volume will specifically focus on a series of systems of representation that go beyond the mere visual reproduction of a given location to construct a network of meanings that ultimately shapes our spatial worldview.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access New Approaches to Cinematic Space by Filipa Rosário, Iván Villarmea Álvarez, Filipa Rosário, Iván Villarmea Álvarez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Filmgeschichte & Filmkritik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Urban Spaces

More than half of the Earth’s population currently lives in urban areas, so there is no wonder that most films take place in such spaces, whether cities, towns, suburbs or slums, since each neighbourhood can inspire at least as many stories as people living there. Urban space has thus become an outdoor film set in which filmmakers look for realism and authenticity, but also for singular buildings, scenic views and well-known landmarks. The economic dimension of these cinematic cities has led local authorities to create film commissions charged with promoting their city as a film location, in an attempt to attract film shoots to the area and then, if the film is successful, a generous crowd of tourists and investors. New York, Paris, Tokyo, Los Angeles, Mumbai, London, Shanghai, São Paulo, Cairo, Rome… the list of cinematic cities includes any place where someone has recorded some sequence some time – from professional film crews to amateur filmmakers. For more than a century, these people have given rise to a vast archive of urban views that have influenced our understanding of the cityscape almost as much as our own everyday environment. Consequently, when someone talks about a missing neighbourhood or a foreign city, we can picture them through our memories – in case we have been there – or rather through their cinematic doubles, which are usually much more accessible than real places themselves.

This book begins with two different ways to represent the urban experience: that of the residents and that of genre filmmakers. In Chapter 1.1, Paolo Simoni discusses amateur moving images of Bologna with the purpose of mapping what he calls ‘the amateur city’, that is, the sum, juxtaposition, stratification, comparison and editing of the gazes of all those inhabitants who have filmed the urban environment at some time. He specifically focuses on the work of five local filmmakers – Corrado Calanchi, Angelo Marzadori, Mauro Mingardi, Luciano Osti and Eros Parmeggiani – who documented Bologna in the post-war years, between the 1950s and 1980s. The close analyses of their respective collections, preserved at Archivio Nazionale del Film di Famiglia, allow Simoni to identify up to three different gazes towards cityscape – the militant, archivist and transfiguring gazes – whose topographical nature can be used to recall and reconstruct the past in many creative ways.

In Chapter 1.2, Anna Poupou explores the role of social and architectural spaces in a series of contemporary Greek art house films that re-enact the generic conventions of the neo-noir and the thriller in the context of the Great Recession, such as Stratos (Το Μικρό Ψάρι, Yannis Economides, 2014) and Wednesday 04.45 (Τετάρτη 04:45, Alexis Alexiou, 2015). These films generate a dark iconography of a cityscape in crisis that challenges the stereotypes of the Athenian imagery, while simultaneously developing a critical discourse on the effects of neo-liberal values and policies on people and places. The neo-noir features allow these films to transcend the Greek national context, providing them with a wider allegorical perspective aimed at an international audience. After all, since we all are trapped in a globalised economic system, what happened in Athens in the early 2010s was also happening to a greater or lesser extent everywhere.

1.1 Memoryscapes

Mapping Urban Space through Amateur Film Archives

In the framework of my research on the representation of cityscapes in amateur cinema, I chose to use the expression ‘amateur city’. With this term, I intend to create a sort of synthesis resulting from the sum, juxtaposition, stratification, comparison and editing of the gazes of the inhabitants who have filmed the urban context for over a century.1 From this perspective, the amateur city that I am looking for can be defined through filtering, selecting and analysing private film heritage as archaeological audiovisual deposits from the analogue era. In this regard, I became especially familiar with small-gauge film materials – 8 mm, Super8, 16 mm, 9.5 mm – evaluated as visual stratigraphy of the last century, particularly from the 1920s to 1980s. From such materials, the representation of cityscapes can be seen and investigated from below, in both a diachronic and synchronic way. Still, the surviving territory of home movies and amateur film production is enormous and has a long way to go to be preserved. The audiovisual sources we can access consist mainly of moving images shot by non-professionals in the private domain for different purposes, previously unpublished and recently digitalised and made available for public use. The film materials I took into account were produced in an urban context by people who basically filmed the same places where they lived, passed through and knew like the back of their hands. As amateurs, they tended to film the objects of their affection.

First of all, I should point out that public space has been one of the main settings of family self-representation, and as such, it has often served as the background of home movie making. People in the foreground filmed themselves creating a cinematic memory of their daily experiences, and of civil and religious rites. This category of materials includes portraits of the places that they inhabit or frequent, as well as film reports on public happenings. Cityscapes should then be explored systematically through all of these representations, as well as through the images of filmmakers who would like to portray the city or its specific places with a clearer intention of reporting it on film.

The Image of the City

If we consider amateur footage shot by inhabitants of a city as their recorded gazes reflecting their ways of seeing, feeling and getting a visual perception of the urban space, and if we collect a large amount of amateur film sequences as sources that are exhibiting a common social practice focused on the city environment, then we could simply reaggregate these glimpses as a cinematic geography framed through amateur images. Using a geodatabase to locate the film shots on a digital cartography, it is possible to draw a mental map that represents the use of the camera within any cityscape. This ‘mapping’ applied to archival amateur film material would recall, from a renewed point of view, Kevin Lynch’s classical study on the image of the city, which, according to him, would be determined by its inhabitants’ perception of the urban space, interpreted and read through a set of identifiable physical elements (1960). Mental maps – often distant from the actual urban cartography – are derived from the dwellers’ descriptions of the locations of everyday life, collected as primary sources that can then produce a geographic visualisation.

Lynch delineates common physical elements and patterns, combinations of which shape the individual’s perception of urban space and formulate urban mental maps. The physical elements are “paths” (streets, walkways, transit lines, canals, railroads), “edges” (boundaries, linear breaks such as shores, railroad cuts, edges of development, walls), “districts” (sections of the city), “nodes” (junctions, mobility hubs) and “landmarks” (buildings, signs, stores, physical elements linked to the urban identity) (Lynch, 1960, pp. 46–48). These five elements are the basis of the concepts of “legibility” – how people understand the layout of a place – and “imageability” – evocation of a strong image in any observer (Lynch, 1960, pp. 9–13), as they facilitate the construction of cognitive maps of the urban environment. Lynch’s theory is a change of perspective in mapping cityscapes and was a stimulus for attempting to reconstruct a cinematic image of the city starting from the gazes of amateur filmmakers: figures moving across the urban space, and in doing so measuring its places with the camera. In short, Lynch’s discourse is crucial in analysing amateur footage, conceiving of a collective gaze made up of many fragments, and employing visual recordings as a reflection of the way people see and live day by day the physical elements of cityscapes.

Amateur Bologna

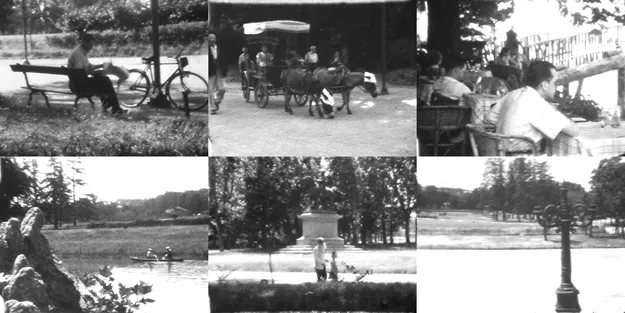

The case study addressed in this essay comes from a survey of the amateur moving images of Bologna, a medium-sized city of fewer than 500,000 inhabitants in Northern Italy. This location was chosen for several reasons, beginning with the availability of a large number of private film collections, the archiving, cataloguing and digitisation of which were crucial. The aim of this survey was to map the amateur city, and the ensuing research was based on consulting approximately 150 film collections preserved by Home Movies – Archivio Nazionale del Film di Famiglia.2 I primarily searched these images for the background and setting of daily life, as well as celebratory moments filmed in public spaces such as squares, parks and streets. Urban spaces easily became the stage for little happenings and rituals, captured by amateur cameras, and in many cases performed and fictionalised for the film device itself and, ultimately, for collecting personal memories (Figure 1.1.1). These spaces are also the setting of political, religious, athletic and playful events filmed by people as personal recordings and testimonies of their being there. Across the various different film materials, I also discovered another perspective: moving images shot by those filming the urban space with a clear intention of capturing the transformations of the cityscape within an independent and non-professional film project. In all the cases, I took into account the figure and the role of the amateur filmmaker – such as the father of the family taking a little camera in his hand or the more technically advanced filmmaker – as “a member of the urban crowd, a participant observer/witness who creates an embodied viewpoint of city life”, as suggested by Julia Hallam (2012, p. 53). In this sense, all the ‘cine-eyes’, all the gazes of the man in the crowd, are useful today as tiles for composing the mosaic of the amateur city. They should make evident and visible how the inhabitants looked at these places and how they lived and self-represented themselves in that urban space. It is just like a patchwork synthesis of visual fragments.

Considering Lynch’s paradigm of the image of the city as a map drawn on the collective perception of its citizens, this essay is particularly focused on the amateur city of Bologna as filmed by small-gauge filmmakers after the Second World War. Accordingly, the selected corpus begins in the 1950s, a period of a great economic development, during which time the practice of amateur filmmaking – primarily in 8 mm – was increasingly becoming part of social practice up until it reached the borders of another technological age in the early 1980s. Moreover, the decades between 1950 and 1980 also coincide with a period of urban growth in Bologna in which the cityscape was transformed, consumerism increased and there were important changes in the local administration.

Figure 1.1.1 Frames taken from various home movies collections.

An overall image of the amateur city resulted from the mapping of amateur film collections: recombined, fragment by fragment, as it was presented in the Cinematic Bologna exhibition (Roberts, 2015).3 The moving images captured by city residents are usually located in the historic city centre, where the landmarks consist of well-known conspicuous buildings and/or monuments, such as the so-called ‘two towers’ (due torri), Asinelli tower and Garisenda tower, the church of San Petronio and Palazzo d’Accursio, both in the main city square, Piazza Maggiore, or the Fountain of Neptune, another icon of Bologna (Figure 1.1.2). These architectural elements of the cityscape perpetually caught in the gaze of amateur cameras give shape to a specific cinematic geography. Thus, the uplands of the sanctuaries of San Michele in Bosco and San Luca, respectively, mark the visual borders of the south and southwest of the city. On the opposite side, the train station and the central gas station signalled the northern limits of Bologna: they are less visible, but even so, remain present. In the 1950s, the ancient city gates still indicated borders – edges – for filmmakers as physical markers dividing the centre from the outskirts and the ring road boulevard for traffic. In some sequences, the latter appear to be an empty space – seemingly land of nothing – until the explosion of traffic in the early 1960s. After that, the ring road looks like an impassable border of automobiles.

Figure 1.1.2 Frames taken from various home movies collections.

Figure 1.1.3 Impressione dei giardini pubblici (Gaetano Carrer, 1949–1950).

Over these decades, the most frequented paths by amateur filmmakers are the main streets that determine Bologna’s historical urban shape: via Rizzoli – via Ugo Bassi and its intersection with via dell’Indipendenza. Some filmmakers were also interested in tram and bus routes, as well as in their nodes: points of departure, arrival and exchange. Particularly crowded – and represented – locations are the football stadium where Bologna FC plays, the racetrack and the main public parks, including Giardini Margherita (Figure 1.1.3) and Montagnola – the latter was traditionally the venue of exhibitions and political happenings, which were later moved to the suburbs, and as a result, less frequently filmed. Other filmmakers represent the district of their residence. Another key piece of the city image was its metamorphosis throughout the 1950s and 1960s, when the filmmakers’ attention was captured by changes in urban planning (e.g. a new ring road that redefined the northern borders of the city), new buildings involving significant architectural work and the transformation of the northern outskirts’ skyline.

A Topographical Cinema: Films as Maps

Bologna democratica (1951) by Angelo Marzadori is probably one of the best examples of an amateur film concerned with mapping the urban space. Its images show the post...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Screen is the Place

- Part 1 Urban Spaces

- Part 2 Architectural Spaces

- Part 3 Genre Spaces

- Part 4 Spectral Spaces

- Part 5 Heterotopic Spaces

- Part 6 Phenomenology of Space

- List of Contributors

- Index