![]()

Part I

Livelihoods, cultures and practices

![]()

1 Sustainable everyday culture from glocal archipelago culture

Katriina Siivonen

Problematizing the harmony between humanity and nature

A strong cultural coexistence with nature is often understood as living one’s life in an ecologically sustainable way. This coexistence can be defined as one element of a tangible and intangible cultural heritage, and the relationship between cultural heritage and sustainable development has been discussed in the heritage work of The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), for example. The work that has been conducted by UNESCO has aimed towards searching for practices where cultural heritage could be defined as sustainable by nature, not only by its intrinsic value of cultural heritage, but also as a guarantee for maintaining or reaching ecological sustainability, as well as other dimensions of sustainability. Investments towards safeguarding cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation in the different corners of our globe, have thus been suggested as being an essential element that will lead to, for example, ecological sustainability (see e.g. Boccardi and Duvelle, 2013).

This is also the situation in the Baltic Sea area, in the Nordic countries (and in Finland as one of these countries) and in one of the Finnish maritime regions, the Southwest Finland Archipelago. As an example, the Archipelago Sea Biosphere Reserve, which is an organization working in a part of this archipelago area for sustainable development and culture, emphasizes the current and past relationship between man and nature in the archipelago as a strength, by claiming that ‘[p]eople in the archipelago have lived in harmony with nature for centuries’ (author’s emphasis; Archipelago Sea Biosphere Reserve 2016a, 2016b). However, there is alarming evidence of the deteriorated condition of the natural environment in the Archipelago Sea. In particular, the addition of excess nutrients as a result of human activities is leading to a dramatic increase in the growth of plants and algae, causing oxygen depletion in the sea. This phenomenon is called eutrophication, and it is only one indicator of human pressure on nature in this area (Lindholm, 2000; Mattila, 2000).

The aim of this chapter is to problematize the idea of harmony between humanity and nature as an expression of ecological sustainability used, for instance, in cultural heritage activities. My focus is on an area where this harmony is seen as an essential part of local identities and culture, the Southwest Finland Archipelago. However, it seems that culture does not always guarantee harmony. There is thus a need for a better understanding of what elements of culture could function as a resource for ecological sustainability and what elements do not constitute strong tools for reaching sustainability (cf. Birkeland, 2014). I will focus on two main questions: first, what expressions of the relationship between humans and nature exist and are valued in the everyday culture of the Southwest Finland Archipelago? Second, what lessons can be learned from this region that could assist us in achieving ecological and cultural sustainability?

In order to answer to these questions, I will analyse two main sources: the results of an analysis by the ethnologist Nils Storå (1993) on the adaptive strategies of the people living in the Åland Archipelago in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries together with an analysis of the current ways that people identify with their home area in the Southwest Finland Archipelago. The latter analysis is based on interviews and observations conducted in the archipelago area during the years 1997–2001.1 The interviewees represent men and women of different ages and professional backgrounds from the inner and outer archipelago, including those with long family roots in the area and those who have settled only recently. Through qualitative ethnological research, their descriptions of both the archipelago area and the important elements of their life inside its borders were analysed (Siivonen, 2008a, see also 2010).

Cultural sustainability as safeguarded cultural heritage

In this chapter, everyday culture is not defined as cultural heritage in its totality. Rather, cultural heritage is seen as selected elements of everyday culture that have been elevated to the special status of cultural heritage, taken into use as cultural resources in society or among a group of people. When different cultural phenomena are referred to as or officially nominated to the status of cultural heritage, they are always consciously defined as such for some specific purpose. Cultural heritage is a central concept with institutional power in both cultural and regional policies around the globe. When cultural heritage is employed instrumentally in this fashion by different administrational organizations representing a state, region or group of people, the goal is to create a strong common identity for a group of people and support social welfare, community cohesion and the economic or perhaps ecological development of the targeted area (Beckman, 1998; Shore, 2000; see also Auclair and Fairclough, 2015).

Recently, discussions on the relationship between culture and sustainability have highlighted the different interpretations of what cultural sustainability means. One established use of cultural sustainability is as a support for the intrinsic value of cultural heritage as a fourth pillar of the sustainability model in relation to the widely-accepted three pillars (ecological, economic and social). However, a broader view of cultural sustainability sees cultural heritage as ‘the fundamental element of sustainability which supports, interconnects and overarches the traditional three pillars [of sustainability], all of which, of course, exist in a cultural context, and all of which can be seen as cultural constructions’ (Auclair and Fairclough, 2015: p. 7). Either way, the longue durée, or continuity, of heritage is often emphasized when defining the relationship between heritage and sustainability – even though change and creativity are commonly seen as important parts of heritage (Auclair and Fairclough, 2015: pp. 1–3, 7 and passim; see also Dessein et al., 2015). The UNESCO conventions for world heritage and intangible cultural heritage are examples of regulations for the safeguarding of cultural heritage (e.g. UNESCO, 1972, 2003). Different national and regional principles for the protection of heritage follow these conventions. Along the lines of these conventions and the like, cultural sustainability is mainly understood as a continuity of cultural heritage, and then as the fourth pillar of sustainability that also supports the other pillars of sustainability as well.

One way of defining cultural sustainability is to see it as a support structure for cultural elements that posit the relationship between people and nature as harmonious (see e.g. Archipelago Sea Biosphere Reserve, 2016b; Auclair and Fairclough, 2015: pp. 6–7). In the Nordic countries, an example of this form of cultural heritage is the Vega Archipelago in Norway, nominated for the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2004, and described as reflecting ‘the way fishermen/farmers have, over the past 1,500 years, maintained a sustainable living’ (UNESCO, 2016a; Daugstad and Fageraas in this volume: p. 181). Another example is the Kvarken Archipelago, a UNESCO World Heritage site that is shared between Sweden and Finland, which has been labelled as of natural heritage due to the geological uniqueness of the area. The impact of the people living in the area, ‘engaged in small-scale traditional farming, forestry and fishing’, is estimated to be ‘negligible’ for the geological value of the region (UNESCO, 2016b).

Defining local cultural elements as cultural heritage to support the ecological sustainability of a certain area takes the harmony between human beings and nature as an obvious determinant of these cultural elements and these cultures. From the perspective of safeguarding cultural heritage, it is then enough to simply identify examples where cultural heritage is understood as contributing to ecological sustainability. However, it is important to investigate whether this assumption is correct, in light of empirical evidence of everyday culture and its relationship to nature and natural resources. For this chapter, I will focus on the Southwest Finland Archipelago.

The Southwest Finland Archipelago

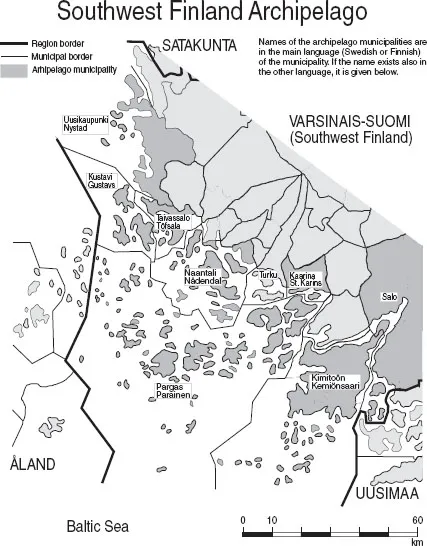

The Southwest Finland Archipelago covers an area of approximately 10,000 km2, containing over 22,000 islands. The area is often seen as an idyllic, semi-natural environment (Figure 1.1). The large and fertile islands in the inner archipelago are suitable for farming, while the islands in the outer archipelago are less favourable. Over the entire archipelago, 75 per cent of the islands – mostly situated within the outer archipelago – have less than one hectare of surface area, and many are largely devoid of any vegetation (Granö et al., 1999: pp. 33, 38). The area is divided into eight municipalities (Figure 1.2) and contains a population of around 17,000 inhabitants (Tilastokeskus, 2005: pp. 92–94; Sisäasiainministeriö, 2007: pp. 56‒57).

Figure 1.1 Kustavi, Isokari in the Southwest Finland Archipelago, 2012.

Source: Katriina Siivonen.

The living conditions in this archipelago have changed as a result of modernization processes in the twentieth century. Earlier sources of livelihood, mainly agriculture including animal husbandry, fishing, hunting and rural shipping, are no longer as profitable and have been replaced by other activities such as the service industries. The area also features some industry that is partly rooted in the seventeenth century. Nevertheless, livelihoods associated with primary production continued to play an important part in the local economy even during the era of modernization (Lukala, 1986: pp. 228–232; Andersson, 1998). During the twentieth century, the population fell steadily, especially in the outer archipelago, where fishing had been one of the dominant livelihoods. However, since the 1970s, the population has remained relatively stable (Vainio, 1981: p. 33; Bergbom and Bergbom, 2005: pp. 57–61).

Ecological adaptation in the archipelago

The ethnologist Nils Storå (1993) conducted his research in the Åland Archipelago, which forms a geographical continuum with the Southwest Finland Archipelago (see the location of the Åland Archipelago in Figure 1.2). The living conditions in these areas are and have always been similar from an ecological point of view, and Storå’s analysis of the adaptive ecological dynamics in the Åland Archipelago is useful here for analysing the Southwest Finland Archipelago.

Figure 1.2 Southwest Finland Archipelago.

In his research, Storå analysed the adaptive strategies of the people who lived in the Åland Archipelago in the eighteenth, nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century in order to explore the relationship between humans and their environment. These strategies are expressed in multiple everyday living practices and, for instance, when communicating with children as part of their socialization process. In Storå’s study, ecological adaptation was understood as a complex combination of ecological, cultural (including technology), demographic, social, legal and administrative aspects of the livelihood activities in the area. The culture of this area in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was shaped by a combination of local self-sufficiency and trade in both local and international markets (for necessities such as grain and salt, as well as iron used in building ships). As culture in this kind of ethnological meaning is located within a complex socio-ecological system, changes in one of these aspects in local culture often has implications for other parts of the system (Storå, 1993). As a consequence of this, the culture in these two neighbouring archipelago areas – the Åland Archipelago and the Southwest Finland Archipelago – has always been in a glocal, interactive process of change.

According to Storå, this local culture contains strongly embedded knowledge about nature, both as a living condition and resource, yet he also identifies a cultural tendency towards the overuse of natural resources in the archipelago in several ways. First, he argues that the human impact on the environment has been so significant that ‘there was already a ‘man-made’ environment dominating the physical landscape’ by the nineteenth century. Second, by referring to Mead and Jaatinen he notes that

[e]ven early periods of population pressure could easily have led to over-exploitation and strong impacts on the limited distribution of land. There already seems to have been a population pressure on land and natural resources by the end of the Middle Ages.

(Storå, 1993: pp. 189, 225–226; ref. Mead and Jaatinen, 1975: p. 75)

The overuse of wood, pasture land and fish that occurred at the beginning of the twentieth century resulted in a need to limit pasture and logging, as well as hunting in the area (Lappalainen, 2004: p. 13). During the twentieth century, the overuse of natural resources was evident as fertilizers became increasingly necessary for agriculture, and the area also began featuring the cultivation of fish (one source of the current eutrophication of the Baltic Sea) to restore the area’s diminished fish resources (Storå, 1993: pp. 189, 223; Hammer, 2000; Mattila, 2000; Vuorinen, 2000). Even since the number of inhabitants has decreased, human pressure on the environment continues to be significant, partly due to rising living standards.

The philosopher Ilkka Niiniluoto argues that the beginning of agriculture changed human beings from a creature that was at the mercy of nature to a creature that is consciously reworking, cultivating and culturalizing their own living environments (Niiniluoto, 2015: pp. 171–172). The period of cultivation in the Southwest Finland Archipelago began in the prehistoric era, even though fishing, hunting and foraging have maintained their popularity during the centuries – especially in the outer archipelago. Currently, the area’s most extensive branch of industry is the service sector (Andersson, 1998), which includes tourism based on an idyllic image of an archipelago culture where humans live in harmony with nature (Siivonen, 2008a: pp. 299–305). This aims to incorporate the archipelago into a mobile and resource-hungry world, where more and more people, material resources and ideas move globally, faster than ever before. Cultural heritage is then used as a resource for promoting tourism. In particular, the romanticized view of nature and the cultural harmony with nature, which are defined by the spirit of eighteenth and nineteenth century Romanticism, are used as a core resource in tourism (Siivonen, 2008a; Niiniluoto 2015: p. 171). To achieve this goal, there is a need to tell a story about archipelago culture as an example of a form of culture that is in harmony with the natural world.

Overall, it is evident that the human population in the archipelago that is part of this socio-ecological system has not, and, in pr...