![]()

PART I

History and Theory

![]()

Chapter 1

Traditional Chinese Urban Form and Continuity

China has a large number of historic cities dating back to thousands of years in history. As the only survivor among several ancient civilisations (Morris 1972), Chinese civilisation continuously evolves and develops over a long period of time. The remaining historic cities offer the lens through which the extremely rich Chinese cultural tradition can be revealed and reconsidered in a new global context. The historic legacy is an important source of local identity and it needs to be comprehensively understood in the process of contemporary urban development. This chapter examines Chinese traditional urban form in general. Its remarkable continuity presents Chinese cities an ideal test ground for the exploration of typomorphology.

This chapter traces the spatial production of primitive society and the emergence of cities in the late neolithic China. Aboriginal understanding of the human-environmental relationship developed through people’s attachment to, and fear of nature into a system of cosmological understanding, which then fundamentally influenced the feudal society of China in later periods. The imperial cities and their design elements are then discussed based on their specific political cultural contexts and are classified into four categories. The traditional design concepts embedded in the development of cities underpin the continuity and change of urban form, and could be regarded as typological thinking which has been deeply integrated in the spontaneous consciousness, if Caniggia’s terminology is followed here (Chapter 3), of Chinese people and their cultural identities.

Primitive urban form and spatial production

China is one of the world’s largest countries with over 9,600,000 sq km of land crossing the east asian landmass bordering the east China sea, Korea bay, Yellow Sea and South China Sea. The coastline on the country’s east extends 14,500 km from north to south. The eastern half of the country has fertile lowlands, foothills and mountains, and the western half of the country is a region of sunken basins and rolling plateaus. The climate of China is greatly diverse: subtropical in the south, subarctic in the north, and is dominated by monsoon winds. The Yellow river and Yangtze river, the two longest rivers crossing the country from the west to the east, were the cradles of Chinese civilisation six or seven thousand years ago.

According to archaeological discoveries, the earliest settlement in China was Yangshao Jiangzhai, a neolithic settlement dated to 5-4000 bC in the Yellow river plain (Sit 2010). Protected by a ditch and a river, the layout of Jiangzhai reflected everyday activities of tribal people who relied on agriculture and animal husbandry. Storage pits, animal rings and kilns were found near houses, with graves outside the ditch, which were all facing a central empty space for gathering and ritual sacrifice. These functional structures were grouped based on the kinship of five independent tribes. Houses were in different sizes for the chief and elder members as well as commoners which represented a primitive social structure. The functional needs, defence and kinship were the basic driving factors determining the form of the settlement, which was similar to primitive settlements of other civilisations.

The development of agriculture resulted in specialised activities (division of labour), surplus and the emergence of social classes, which created necessary conditions for the formation of cities.1 social elites built cities in their embryonic forms to protect and organise non-agricultural pursuits in the late neolithic period. Chengtoushan in today’s hunan region was such an example dating to about 4000 BC. Although small in size, the city was surrounded by stamped earth and moats with four gates in the north-south orientation, and a platform in the centre presumably for large structures (Sit 2010). There were also graves of the elites, small houses and pottery areas for their families, servants and armies. The walled and raised centre for large structures were features also found in early Mesopotamian cities (Morris 1972), although the function of the centre of Chengtoushan was likely to be administrative rather than religious. Such an embryonic form showed the transition of cities from fulfilling merely functional needs to reflecting classes and labour divisions in the evolved society.

One of the earliest proper cities in China was erlitou built during about 1900-1500 BC in the Xia (2070-1600 BC), at today’s Henan province (Zhuang and Zhang 2002). Two large palaces with roofed corridors enclosed on four sides were discovered in close proximity, which indicated a much stronger political power emerging in society. Zhengzhou in the same region built three hundred years later as the capital of shang showed more archaeological evidences of the layout of early cities: city walls of a regular shape, the north-south orientation, an administrative centre on the raised platform and the clear functional division which saw pottery and bronze workshops outside the inner wall and palaces and houses inside.

Sit (2010: 76) stated that the construction of Zhengzhou witnessed a new urbanism in the shang period (1600-1046 bC) which became the base of Chinese imperial cities. This statement was pertinent because of the shared conceptual underpinning of the physical forms of cities in the Xia and Shang and later feudal dynasties. Many archaeological sites and inscriptions on oracle bones of the Shang suggested that successive kings of Shang commonly practiced divination to make important decisions such as the relocation of capitals, wars, large scale constructions and so forth (Wang 2005). The connection between natural and social phenomena was believed to be revealed through six-four hexagrams which were carried on during the Zhou (1046-221 bC) and recorded in the divinatory book Zhouyi (Classic of Changes) (De bary and bloom 2000: 25). It was from Zhouyi that traditional cosmology, philosophy and epistemology was systematised and further developed during more than two thousand years of feudal society and in imperial cities.

Imperial urban forms and design elements

The earliest understanding of human-environmental relationship as recorded in Zhouyi was the close connection among nature or the universe, form (physical appearances), symbols (abstraction) and meaning (natural rules and principles). Through the two opposite figures yin and yang, all creatures in the universe were developed, and the principles of change could be understood and managed (Wang 2005: 38). In other words, the city construction had to rely on ancient astrology, the relationship between natural environment and the city, and mathematic relations among man-made objects and their symbolic meaning. The ultimate goal of form-making and human activities was to coordinate with the universe. This concept was interpreted as different principles or moral codes in such dominative Chinese philosophies as Confucianism (Lizhi), the Guanzi, Taoism and fengshui to bridge the classic thoughts with real practices, which were developed mainly in the late Zhou (including the spring and autumn period and the warring states). Since the first emperor of Qin unified China on 221BC, imperial cities were heavily influenced by them due to the state promotion.

City as political symbols

From the Qin to Tang (618-907 aD), most Chinese cities were built for administrative purposes because agriculture was the foundation of society while commercial activities being deliberately suppressed (Gaubatz 1998, Xu 2000). Unlike medieval cities in Europe where urban forms were shaped by religion along with commercial and defensive needs, Chinese cities served as political symbols under the absolute power of emperors whose ideology was to pursue the eternity of his governance by abiding natural principles which were believed to be followed by all creature. Self-endowed with a title of the son of the heaven, emperors regarded cities as the media to convey the power of the heaven to consolidate their governance on earth. Similar ideology was adopted by regional governors in the construction of their governing cities.

Confucianism held a dominative position as the official teaching of the state during the han (206 BC-220 AD), of which the philosopher Confucius systematised earlier rites and ideas into a moral code of social behaviour in the 5th century BC. Confucianism proclaimed rational and authority established by the state, as well as the metempsychosis as buddhism. It advocated that the order of the world consisted of the heaven, the earth, emperors, ancestors, masters and common people as the positions descended in society. Chaos, absence of officially sanctioned and enforced rules was seen as the greatest evil to be prevented (Moffett et al. 2003). It intended to recover Lizhi (rites of the state) derived in the Zhou for social stability under imperialism.

The materialisation of Confucianism and Lizhi on urban form was the ideal City model recorded in Kaogong ji as part of the Ritual Book of Zhou (Zhouli), which was in fact written during the han containing materials from the previous period. According to Moffet’s (2003: 93) translation, the ideal City model suggested that,

A capital city should be oriented to the cardinal directions and have a square plan roughly 4000 feet on each side. In the wall that surrounds the city, there should be three gates in each side, and roads projecting out from these establish the grid of the city’s plan. The central road on the south is the entrance for the major thoroughfare, nine cart lanes wide, which runs north to the palace complex. The palace itself is walled off from the rest of the city, preceded by an impressive courtyard and flanked by place of worship: the ancestral temple (to the east), and an altar to the earth (to the west). The city’s marketplace is to the north of the palace compound … walls and a moat around the city provide protection from enemies without, while walls around the palace and residential blocks establish barriers that clarify the social hierarchy … (Moffet 2003: 93)

The perhaps earliest city following this ideal model was the capital city of the state of Lu built in about 859 bC in the warring states (Zhuang and Zhang 2002). Its orientation, the shape, street network, and the central axis were evidently following the ideal setting, except that the palace was slightly away from the centre to the east and no archaeological trace of the market places was found (Fu 2001). Administrative cities built in later years more or less reflected these features described in the ideal model (Yang 1993). For instance, suzhou, built in 514 bC as the capital of the state of wu was approximately in the cardinal orientation (north-south orientation), rectangular in shape, and had two or three gates on each side of the wall and a gridiron street network, with the palace in the centre. The names of gates of suzhou symbolised the hegemonic ambition of the king (Xu 2000). Chang’an, the capital of Han since 206 BC, was essentially a city of palaces that occupied two third of the walled area, like the capitals of Qin. The approximate shape, number of gates, and locations of markets were features embedded in Confucianism and Lizhi, but the successive palaces were not in the centre. Luoyang, a later capital of Han was also a modified version of the ideal model, evidenced in the street network and the central axis organising ritual buildings as well as dimensions of walls in sacred numbers, although there were dual palaces inside (Dong 1982). Jiankang (today’s Nanjing) in Southern Dynasties (420-589) also showed great similarity to the ideal model (Chapter 5).

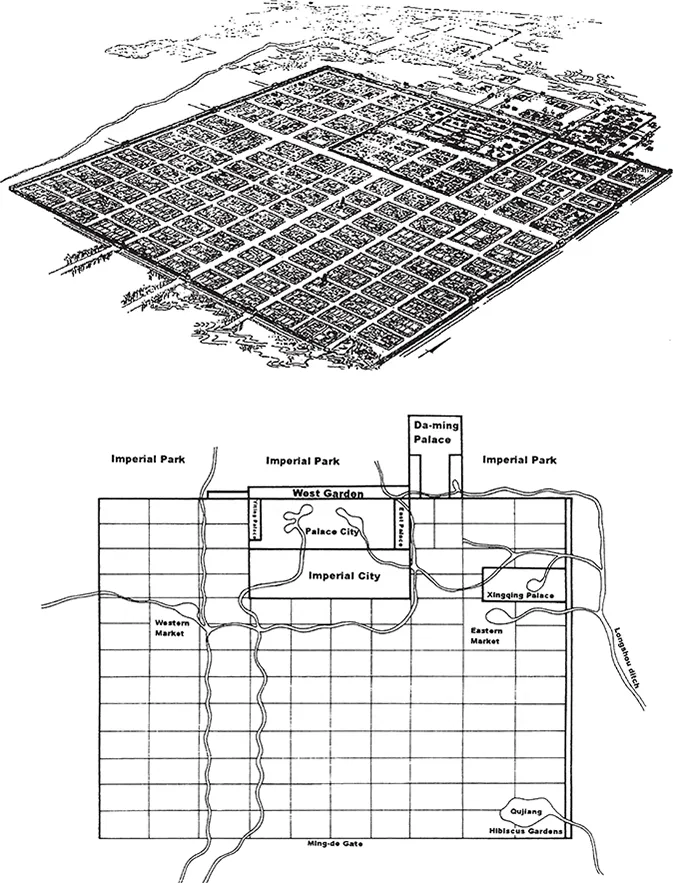

Figure 1.1 The aerial view and plan of Chang’an of the Tang. Source: Chinese City and Urbanism, V.F.S. Sit, 2010, World Scientific Publishing

The most influential city embedding the political symbolism was the capital city Chang’an in the Tang, when Confucius doctrine was promoted the most by emperors of Tang (Figure 1.1). As a pre-planned city, the walled rectangular area of Chang’an was divided by the street grid into 109 walled and controlled residential wards called lifangs. The walled palace contained the emperor’s audience hall and his residence, from which a central axis crossing the entire city was clearly visible. The two walled markets were located on the south of the palace rather than on its north due to the north-central location of the palace which were variations of the ideal model. Chang’an was cardinally oriented and had three gates on each side of the wall. The dimensions of the city and its lifangs were mathematically related (Fu 2001). Due to its formality, orderliness and prosperity at the time, Chang’an became the model for the development of Japanese capital cities such as Heijokyo and Heiankyo, and influenced Korean cities as well (Morris 1994, Steinhardt 1986). As the largest planned and walled city (87 sq km) in the world at that time, Chang’an was a remarkable political symbol representing the highest dominance of the political power under which commoners’ daily lives were strictly managed and compromised in the functionality of the city.

As evidenced in Chang’an and other cities during the same period, the political symbolism was clearly reflected in urban form arrangement. First of all, as administrative centres of the region, cities were occupied largely by palaces, ritual temples and government buildings as well as social elites’ residents. Unlike european medieval cities where people’s daily lives played a vital role, Chinese cities before and during the Tang were not for commoners since commercial activities, which were suppressed following Confucianism, took place only within designated markets. Residents were strictly controlled in their lifangs with curfew applied in early years of the Tang (Li 2007, Liang and sun 2003). A unique phenomenon in early imperial cities was that urban as the area inside the wall was not very much differentiated in terms of land uses from rural areas outside the wall (Xu 2000). In other words, the physical boundary of the wall did not conceptually define residents’ identities because they all relied on farming the land and were largely self-sufficient. This was evident in the advanced development and flourishing o...