![]()

1 Introduction

A quick internet search reveals that the term geopolitics is hardly ever associated with the term knowledge-based economy. Journalists, debaters and politicians do not make such a link in their articulations and the textbooks of geopolitics, political geography, economic geography and urban studies are equally silent on the issue (see, however, Salter 2009). Yet, the air is full of popular and scholarly argumentation concerning how we are currently living in an era marked by the prominence of knowledge in all societal, economic and cultural developments, as well as pronouncements about the knowledge-intensive form of capitalism as an important subtext for inter-state relations and inter-spatial competition. Hence, it seems it is high time to begin pondering what the interconnections between the knowledge-based economy and geopolitics look like. The purpose of my inquiry is analytical and conceptual: the goal is to raise new questions rather than answering old concerns.

When I began this project I soon realized the ambiguous nature of the term knowledge-based economy and some related terms such as knowledge economy, information economy, new economy or the like. The fact that the knowledge-based economy has become an idée fixe in political debates within the past two decades does not give proof of its value as a scholarly concept. Indeed, one may argue that the knowledge-based economy is a somewhat popular and hollow policy term and that the competition state, neoliberalism, global capitalism, financialization, information capitalism or the like would work better in a geopolitical analysis of the contemporary political–economic condition.

My solution to this conceptual issue has been to think through the concept of knowledge-based economization. I thus shift attention from the economy toward processes of economization (see, in particular, Ҫalişkan and Callon 2009). The concept of knowledge-based economization refers both to the material processes of knowledge-intensive capitalism (including subject formation), and to the processes whereby this form of capitalism is constructed discursively through imageries and objectifying social practices. My central claim is that the phenomenon of knowledge-based economization includes significant geopolitical dimensions that can be exposed through an act of conceptualization and with the help of different research materials ranging from expert interviews to popular academic literature, observations, policy documents and statistics.

Geopolitics is almost invariably conjoined with the notion of territorial control of natural resources and territorial expansion as states vie for power and seek to exert influence on other states. Accordingly, geopolitics typically focuses on international power relations and power plays based on military influence within a set geographical area. Indeed, the very concept of geopolitics is often associated with a dangerous militaristic form of political reasoning which may lead to all manner of violent events. Stefano Guzzini (2014), for instance, proclaims that the effect of a geopolitical world view is a fundamental militarization of states’ foreign policies.

In an orthodox view, geopolitics is treated as a synonym for politics of territorial force (and spheres of influence) and in particular for states as primary users of such “hard force” (see, e.g. Mead 2014, 69). More often than not, geopolitics is still understood to denote drawing state borders, building nations as definite territories, constructing domestic social order through spatial techniques of coercion and consent, controlling territorial spaces through new military technologies within and beyond a given state, as well as geographical and historical justifications of territorial claims (Moisio 2013). The concept of geopolitics is therefore almost without exception associated with the idea of the purportedly territorially consolidated twentieth-century European state and the wider system of military strategy and power which still characterizes the powerful imaginary of the “Westphalian” inter-state system. As a persistent form of reasoning, the classical geopolitical perspective discloses some of the key political characteristics of the “industrial era” of the nineteenth and twentieth century: command of territory and natural resources were understood as pivotal dimensions of inter-state rivalry and as fundamental constituents of territories of wealth, power, status, security and belonging (cf. Maier 2016).

Today, variants of classical geopolitics persist in the ways in which politicians, foreign and security policy experts, military strategists, scholars and the general public make sense of international affairs. However, it is similarly stressed that inter-state competition over territories belongs to the past, and that “democratic governments” operate through a qualitatively entirely new set of state strategies. Geoff Mulgan (2009, 2), the former director of policy under the British Prime Minister Tony Blair, states how

Past states wanted to grow their territory, crops, gold, and armies. Today the most valuable things which democratic governments want to grow are intangible: like trust, happiness, knowledge, capabilities, norms, or confident institutions. These grow in very different ways to agriculture or warfare. Trust creates trust, whether in markets or civil societies. Knowledge breeds new knowledge. And confident institutions achieve the growth and societal success that in turn strengthens the confidence of institutions. Much of modern strategy is about setting these virtuous circles in motion, whether through investments or programmes or by creating the right laws, regulations and institutions.

This narrative on the shift from tangible to intangible “things” discloses a great deal of the key aspects of the transformation from natural resource-based national economies toward the so-called knowledge-based economies. The book at hand is an attempt to conceptualize the geopolitical in the latter context. I argue that knowledge-based economization emerged gradually from the 1980s onwards as a result of the turbulent era in world economy and politics (which began already in the early 1970s; for this crisis, see Hobsbawm 1996), and took an increasingly geopolitical form in the 1990s.

Towards a political geography of economic geographies

Developing a geopolitical perspective on the knowledge-based economy requires adopting a theoretically sophisticated notion of geopolitics which transcends its pervasive orthodox connotations. Since the late 1980s, critical scholars began to broaden the narrow understanding of classical geopolitics. John Agnew and Stuart Corbridge (1995, 211), to name but one example, referred to a geopolitical struggle which they conceptualized as an effort “by dominant states and their ruling social strata to master space – to control territories and/or the interactional flows through which modern terrestrial spaces are produced”. In such a view, geopolitics is about mastering both territorial and relational spaces and producing spatial orders through discourses and practices.

Notwithstanding the significant conceptual developments in the field of critical geopolitics over the past 30 years, it is not uncommon today to see the narrow territorial definition of geopolitics in scholarly literature – to say nothing of public discourse. To illustrate, the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the political developments in eastern Ukraine in 2014 were rapidly scripted in terms of geopolitics. Politicians, commentators, journalists, civil servants and scholars in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) world and beyond were quick to classify the conflict as geopolitical. But in so doing, they also tended to place the term geopolitics in the past. While the crisis itself was interpreted in terms of twentieth-century geopolitics, this form of political action was nonetheless understood as entirely anachronistic. It was argued that some states such as China, Iran and Russia (as opposed to the US and the EU) had never given up practicing hard territorial power and were now making “forceful attempts” to overturn the “geopolitical settlement that followed the Cold War”, as Mead (2014, 70) put it in Foreign Affairs. Mead continues revealingly how

So far, the year 2014 has been a tumultuous one, as geopolitical rivalries have stormed back to center stage. Whether it is Russian forces seizing Crimea, China making aggressive claims in its coastal waters, Japan responding with an increasingly assertive strategy of its own, or Iran trying to use its alliances with Syria and Hezbollah to dominate the Middle East, old-fashioned power plays are back in international relations. The United States and the EU, at least, find such trends disturbing. Both would rather move past geopolitical questions of territory and military power and focus instead on ones of world order and global governance.

(Mead 2014, 69–70)

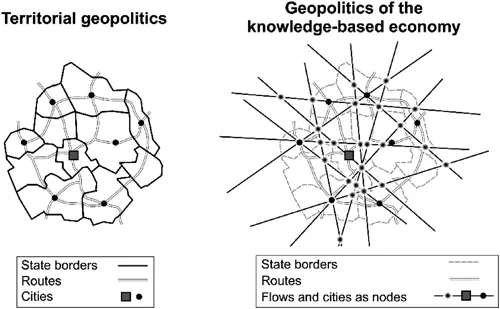

This quote is exemplary, not exceptional, of a logic according to which “geopolitical competition” and “liberal world order” are opposite developments. In such a temporal articulation, whereas the twentieth century was characterized by the “dark geopolitics” of inter-state rivalry and “territorialized” friend–foe relations, the contemporary era is experienced in Europe and the US as if it were marked by a relative inapplicability of state territory with respect to territorial conflicts and inter-state competition. This fact notwithstanding, it has been remarkably rare to discuss the concept of the geopolitical in the context of those political imaginaries that frame the world in terms of economic expansion, connectivity and pace or global integration and connectivity (cf. Sparke 2007). And yet, these imaginaries have become increasingly salient in state-centric political debates on national interests, national security, national identity and foreign policy. In such a perspective, the world is increasingly becoming a network consisting of urban hubs, wider “network-regions” and what Ong (2006) calls economic zones in which surplus value is formed and which are pivotal in controlling the movement of money, information, talent and innovative human behavior. This perspective, therefore, effectively reveals the geopolitics of relational spaces that partly, but definitely not entirely, characterizes the early twenty-first century and which is the topic of this treatise (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Simplified visualizations of the parallel worlds of the contemporary geopolitical condition.

In public policy and mainstream academic spatial planning discourse, the nodes and hubs of the global networks through which the “global flows” are being actively re-territorialized have been, particularly since the 1990s, understood as cities, city-regions and urban spaces and related micro-spaces which together contribute to the building of “global cities”, “smart cities”, “creative cities” or “happy cities”. The development of these new spaces would not only significantly contribute to capital accumulation in the future but also render obsolete “geopolitics” such as the military control of vast territorial spaces and strategic locations. Accordingly, the preceding state-centered era epitomized by the term geopolitics has been replaced by the notion of the international competitiveness of the state based on generating competitive advantages (of nations) through different kinds of spatial formations as well as through new kinds of citizen subjectivities.

Examples of this kind of geopolitical logic are not difficult to find. Indeed, a sort of global knowledge-production industry dealing with the novelty of the relational global political order has emerged concomitantly with the so-called knowledge-based economy. Khanna (2016a) writes in The New York Times how the US is actually reorganizing itself around “regional infrastructure lines” and “metropolitan clusters that ignore state and even national borders”, and that the problem is that a political system which still conceives of the US through its fifty member states “hasn’t caught up”. Arguing against such a territorial view, Khanna (2016a) goes on to say that these fifty states “aren’t about to go away, but economically and socially, the country is drifting toward looser metropolitan and regional formations, anchored by the great cities and urban archipelagos that already lead global economic circuits”. This serves as the rationale for Khanna (2016a) to make a normative policy recommendation. The author suggests that rather than channeling investments into “disconnected backwaters”, the US federal government should focus on helping the “urban archipelagos” or “super-regions” to prosper.

It is interesting that this kind of geopolitical narrative, whereby particular infrastructural and economic connections are viewed as superseding traditional state-centered geopolitical markers, has become increasingly popular since the 1990s (see, e.g. Ohmae 1993). Indeed, Khanna’s (2016b) Connectography is just one among the many attempts to tell a story about the ways in which the future is being shaped less by states/nations than by connectivities of hubs and flows in the age of knowledge-intensive capitalism. Accordingly, connectivity becomes a crucial resource in the emerging “global network civilization” in which “mega-cities compete over connectivity” and in which state borders are increasingly irrelevant. It is a de-territorialized world marked by conflict over internet cables, advanced technologies and market access; a new world where novel energy solutions and innovations more generally eliminate the need for resource wars:

The 21st century will not be a competition over territory, but over connectivity – and only connecting American cities will enable the United States to win the tug of war over global trade volumes, investment flows and supply chains. More than America’s military grand strategy, such an economic master plan would determine if America remained the world’s leading superpower.

(Khanna 2016a)

This view of the world goes to the heart of what in the book at hand is conceptualized as the geopolitics of the knowledge-based economy. From the perspective of “connectography”, national interest is today defined differently than in the past, both socially and spatially. It is a new world in which the state is not only challenged, for instance, by global cities, global city-regions and megaregions (for a discussion of these, see Harrison and Hoyler 2015; Moisio and Jonas 2017), but also re-constructed through these spaces. It is a world in which large cities and urban agglomerations are conceived as crucial sites of a new type of global governance. So pervasive has the hub-centered imaginary grown that scholars are increasingly comprehending the new social organization of the world as indicative of a geopolitical shift from sovereign territorial states to relational city networks (Jonas and Moisio 2016). Peter Taylor (2011, 201) states revealingly how

The prime governance instrument of the modern world-system has been the inter-state system based upon mutually recognized sovereignties of territorial polities. It is possible that we are just beginning to experience an erosion of territorial sovereignties and their replacement by new mutualities expressed through city networks. This is what the rise of globalization as a contemporary, dominant ‘key word’ might be heralding.

These processes may already be under way. But the preceding articulation is also a form of productive power: it reveals some of the dominant ways in which political agents in the OECD sphere in particular comprehend the transformation of global political conditions in the age of globalization. These agents also act upon such a comprehension. In other words, the “connectography” view of the world is in essence a geopolitical one, and it plays an increasingly important role in the context of contemporary strategies and ideas of state territorial restructuring.

I will argue that the hub and flow imaginary is at the heart of contemporary geopolitics. The link between these imaginaries, knowledge-based economization and the restructuration of the state is however rarely debated. This is the case because the geopolitical is often seen to be separate from the issue of regional development and policy, and because the distinction between geoeconomics and geopolitics is still pervasive. Furthermore, the economic geographical literature since the 1990s has more or less naturalized the relational view that the shift toward a knowledge-based economy implies that the capability of regions and their nodal cities to support learning and innovation is a key source of competitive advantage of the state or nation (for a useful discussion, see MacKinnon, Cumbers and Chapman 2002).

The economic geographical understanding of the hub and flow nature of the contemporary world has played a tremendously productive role in the political–economic developments that have taken place during the past three decades. This understanding is driven in particular by the needs of the purportedly knowledge-driven and conceivably global (understood often as existing above the nation state) economy. This is also disclosed by the fact that new urban formations and associated social experiments have been given a prominent place in the political and policy agendas in the OECD states and beyond during the past decades.

One of the key claims of this book is that the contemporary geopolitical condition is characterized by two processes and related imaginaries. The first is centered on issues of territorial power and the associated purportedly old-fashioned territorial power plays which take their motivation from military strategy, natural resources and territorially rooted identity politics. The second is structured around “hub and flow imaginaries” concerned with the state and world that seem to make state territory and military conquest increasingly obsolete. This process and related imaginary touch less on natural resources and military calculation and conquest but also contain a significant amount of territorial politics: it can be understood as a historically contingent process to produce territories of wealth, security, power and belonging. More importantly, the twin processes of the contemporary geopolitical condition are not mutually exclusive but take place simultaneously and may be entangled – generating various context-specific spatial formations, as well as tensions and contradictions. In other words, territorial competition and the purportedly liberal world of knowledge-intensive capitalism are not mutually exclusive but rather parallel developments that co-constitute the contemporary geopolitical condition. In sum, it is analytically untenable to conflate the ongoing territorial power plays solely with the ostensibly geopolitical world of the twentieth century, but it is equally problematic to comprehend the contemporary processes associated with hubs and flows ...