![]() Section 1: Itineraries and Spaces of Selling

Section 1: Itineraries and Spaces of Selling![]()

Chapter 1

West End Shopping with Vogue: 1930s Geographies of Metropolitan Consumption

Bronwen Edwards

In 1937 Vogue published a revealing article, ‘Shopping – then and now’.1 It compared fashionable West End shopping in 1916 and 1937, concluding that ‘in twenty-one years the whole essence of shops and shopping has changed’.2 According to Vogue, the slow-paced, exclusive formality of West End consumption at the end of the Edwardian age had been replaced by the fleeting, self-consciously modern shopping cultures of the 1930s: ‘today the big shops are ever a triumph for tomorrow.’3 Significantly, the article highlighted the spatiality of shopping within this account of transformation, particularly the mechanism of travelling to the West End for a 'day in town' and the pleasurable experience of the city's streets. This chapter explores these spatial concerns, examining how networks of fashionable consumption centring on the West End, and the configuration of shopping routes within the area, formed integral parts of both metropolitan fashion cultures and of conceptions of London as a shopping city, as represented and constructed in Vogue.

The kind of shopping addressed here is significantly different from the flourishing lower middle-class and affluent working-class consumption that has formed the focus for existing inter-war studies.4 These histories do not account for the continued importance of central London as a shopping hub, evident from both retailer strategies and the commentaries contained in magazines such as Vogue, tourist guides, and newspapers.5 By the 1930s shopping content was an established component of the women's magazine, and was instrumental in its construction of femininity.6 Vogue, particularly, forms the central pivot of this chapter. It was a very successful women’s magazine concerned with fashionable dress and fashionable living, broadly espousing the cultures of the affluent middle and upper-middle classes.7 The British edition began publishing in London in 1915,8 and whilst Vogue certainly invites an exploration of the ‘London-ness’ of its fashions, this chapter foregrounds the geographies of shopping cultures. Constructions of fashion and shopping were of course intertwined, so that fashion features, shopping advice columns and advertisements simultaneously provided a monthly roundup of information on the latest fashion developments and the best buys. In Vogue, shopping was about pleasure and fashion, rather than about basic domestic provisioning.

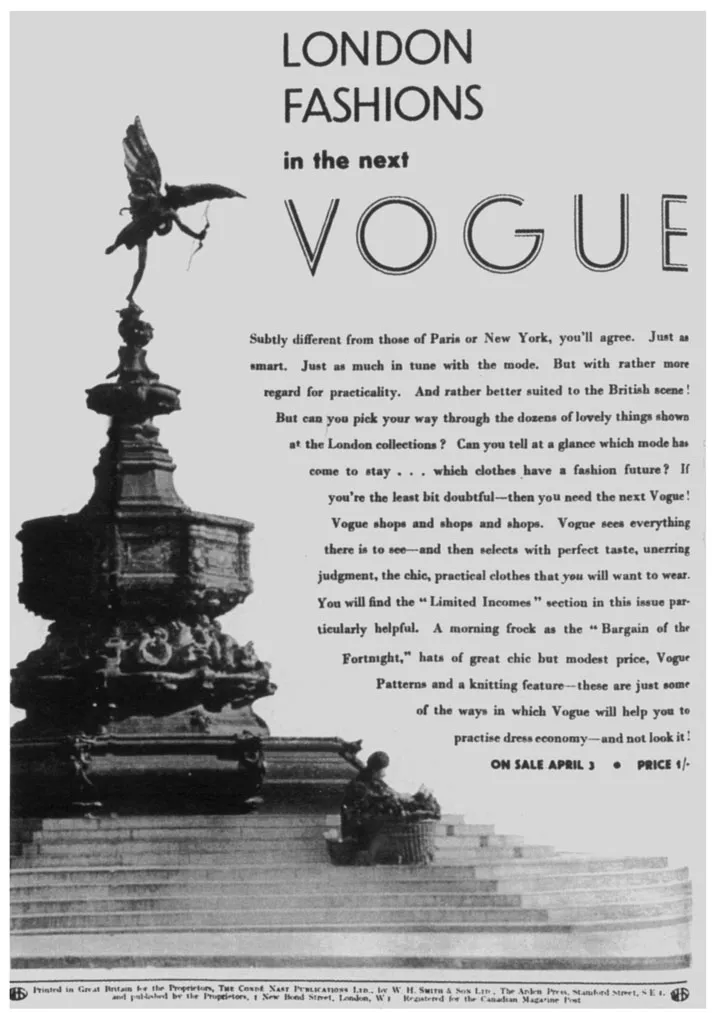

Figure 1.1 Statue of Eros at Piccadilly Circus, illustrated on the back cover of Vogue, 20 March 1935. ©Vogue/The Condé Nast Publications Ltd.

Vogue’s shopping took place almost exclusively in the West End. This chapter has ‘place’ at its heart and considers how maps, routes and networks were important in the way the West End functioned and was conceptualised, looking particularly at the makeup of routes within the West End, an approach that has been relatively underdeveloped within existing work. Rappaport has interpreted the late Victorian shopping article as an urban tour guide.9 This study develops this idea, considering more carefully the meaning of the precise geographies of consumption within the magazine’s shopping information, in the context of the 1930s. It argues that it was not just the design, the fashionability and the branding of goods, but also their association with very specific West End locations, that was important within Vogue’s representation of feminine consumption cultures.

The West End was an area that encompassed a number of smaller retail districts, including Kensington High Street and Sloane Square. However, at its heart was a tight cluster of streets around and between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Bond Street and Piccadilly, which was acknowledged as ‘London’s most fashionable shopping district’,10 and formed the focus for shopping in Vogue. Significantly, this shopping geography runs contrary to the existing historical narrative of the inter-war period, which has overlooked the shops and shopping of central London. A combination of assumptions about the inter-war decline of the big London department stores, the impact of national economic depression on retail, and the relative importance of the suburban and provincial shopping street have drawn attention away from the centre.11 Histories that have dealt with the metropolis have either been concerned with the department stores, tailors and outfitters of the late nineteenth century,12 or with the boutiques of Carnaby Street and the Kings Road in post-war ‘swinging London’.13 The West End of the 1930s is therefore ripe for reconsideration.

The first part of the chapter, ‘A trip to town’, uncovers the distinctive role of the West End in Vogue’s treatment of shopping: as a hub of fashionable consumption within British shopping geographies, and as the destination of pleasurable, purposeful shopping trips. The second part, ‘Mapping the West End’s streets’, uses the ‘Shop-hound’ shopping column to examine Vogue’s West End more closely, showing how its identity was constructed from different streets and routes. The third part, ‘Hiding consumers’, considers the significant absences from the magazine’s West End, which highlight the class and gender-inflected nature of this version of the city. This allows conclusions to be drawn about the ‘edited’ and ‘virtual’ nature of the shopping maps, and suggests the usefulness of the concept of the ‘imagined city’ in deciphering the meaning of magazines’ shopping narratives.

A trip to town

The ‘trip’ was an important mechanism with which 1930s Vogue discussed shopping, and constructed its shopping geographies. This ‘trip’ involved journeying to a particular shopping area: the West End, whose shopping crowds were therefore formed substantially of those who lived somewhere else. The trip was shown to involve a sense of occasion, whether the shopper travelled the short distance from Hampstead for an afternoon, from suburban Surbiton for a day, or from Yorkshire for a precious week. Indeed such explicit distinctions between categories of reader were often collapsed by the magazine, which ascribed to all the same adhesion to metropolitan cultures. This reflected a deliberate attempt to broaden the appeal of the magazine’s contents, but also provided a comment on the London-centric nature of the cultures of England’s social elite.

The Vogue shopper was not presented as a tourist, disoriented by the city. Neither was she a flaneuse, with the term’s connotations of rambling and spectating in London’s streets. Her visit was altogether more purposeful, although it was still essentially pleasurable. Whilst women depicted in Vogue’s society news and glossy advertisements were confident urban habitués, the shopping columns also addressed those who were partial strangers to the city, but who did not want to be recognised as such. The magazine presented itself as an important source of ‘urban knowledge’ for these women’s West End expeditions.14 This set of spatial relationships were clearly expressed in articles such as ‘8 hour day in town’:

We can’t advise you too strongly to plan your day several days ahead … with as much care and cunning as if it were a trip to the tropics. List what you want to buy. If you are shopping for your family and house, make a note of all the necessary data. (Your husband’s collar size, your children’s measurements, the area of the lawn.) Collect swatches of all your existing clothes, so that the things you buy will fit into your colour schemes.15

Enabling the customer to purchase everything in one place was an advantage much trumpeted by the owners of department stores from their early days, and would seem to fulfil the requirements of an efficiently planned trip. It is certainly true by the 1930s the department store was a well-developed format, often incorporating a myriad of departments, which meant that a trip to town could conveniently take place within one store. This suggests a potential negation of the importance of geography within shopping and retail practices, allowing the store to operate independently from its location and diminishing the relevance of its proximity to other businesses in the shopping area. Women’s magazines occasionally used the single-store shopping trip as a genre of shopping article. One such article on shopping at Harrods and Selfridges advised:

At last you’ve booked your day – for a trip to town. You simply had to. You want a spring suit. Your skin looks alarmingly post-winter. It’s Leslie’s birthday in a week. Emma is murmuring about the glass cloths. The sun parlour wants redecorating. Your husband’s pullovers are a sight. Old Crabtree says don’t blame him if you have no cut flowers from the garden this summer. ‘A day!’ you think, ‘I need a month. It’ll take me half a day just travelling from one place to another, from dress shop to beauty salon, on to a toy shop, a decorator’s, a man’s shop, a seedsman’s and so on.’ Yes, but need you? Probably you’ve no idea of the versatility of the modern ‘department store’ where you can cash cheques, have beauty treatments, chose from the latest Paris models, attend an auction, watch a television programme, read and write letters, buy anything on earth from a candle to a cockatoo.16

Whilst historians have frequently identified the department store’s nature as ‘universal provider’ as one of its defining features, they have generally failed to sufficiently interrogate the claims for department stores’ self-sufficiency. Whilst spatial convenience might have been appropriate for the kind of every-day provisioning associated with grocery shopping, it went completely contrary to the nature of the metropolitan shopping cultures examined here. This research has discovered that the single-department-store shopping trip was largely an occasional editorial conceit and department store advertising strategy, which bore little resemblance either to the magazine’s shopping geography as a whole, or to department stores’ broader business strategies. This chapter argues that a shopping trip was neither easily nor desirably contained within one department store. The narratives of West End shopping within magazines and guidebooks, and the design, display and spatial strategies of stores, suggest that it was in variety and multiplicity that the appeal of West End shopping cultures lay: in practices of browsing and choosing, both between purchases and between different stores, processes that were pleasurable, and served to negotiate fashion and construct identity.17

It is highly important that the shops found in Vogue clustered along very specific, and largely West End, streets. This coincides with the findings of a strong body of work within consumption studies, which has highlighted the specificity of place, differentiating shopping cultures and consumers as urban, suburban, or provincial. For example, late nineteenth-century emergent consumer society has been identified by historians as essentially metropolitan in character,18 singling out certain cities, notably Paris, Berlin, London, New York and Chicago, as primary locations of modern shopping cultures, often linked to their operation as fashion cities within an international arena.19

Location was certainly a central tenet of the emergent professional architectural concern with retail planning. In their important 1937 manual, Smaller Retail Shops, Bryan and Norman Westwood advised, ‘General proximity to other shops of the same trade, or same degree of luxury in special trades, is an advantage because it creates a centre for the particular trade, or a place where a particular type ...