![]()

Chapter 1

To Peg or Not to Peg, That is the Question

Exchange-rate crises are awful, harrowing spectacles, analogous to bank panics and stock market crashes, with terrible consequences of their own. The past decade has witnessed numerous currency crises in developing states that many had thought were making economic progress. Mexico suffered a peso crisis in 1994, numerous Asian states suffered crises in 1997, Russia devalued and defaulted on its debts in 1998, and Brazil was forced to devalue in early 1999.

The consequences of these crises are familiar to those that followed these events but are still striking when listed. If the government has agreed to exchange its currency at a given rate, governments frequently lose billions of dollars of foreign exchange reserves as investors race to sell the government’s currency. In 1994, the Bank of Mexico lost $15 billion, half of its reserves, in trying to maintain its exchange rate for almost a year before the crisis (Banco de Mexico, 1995, p.41). In the end, the value of a country’s currency drops suddenly, making the price of imports jump. People lose purchasing power in their wages. Banking crises erupt as banks often fail once they are unable to service the costs of increased external debt (Kaminsky and Reinhart, 1999; Eichengreen, 2003). The loss of foreign and domestic investment damages the growth of the economy. One famous study from many years back estimated that 30% of governments fell within a year after the devaluation (Cooper, 1971, p.28-29). The governments that end up in charge of cleaning up the mess must often accept the policies the International Monetary Fund (IMF) advises as conditions for a loan. In addition to all of this, the effects of the currency crisis can spread like a contagious virus and damage confidence in neighboring economies. The devaluation of the Thai baht in 1997 demonstrated this spectacularly as the crisis spread into the financial markets of Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

The number and severity of these crises has prompted scholars to look again at the causes of currency crises. In most of the literature on speculative attacks and currency crises, speculative attacks are caused either by poor economic fundamentals or self-fulfilling prophesies and panics.1 In some economic models, inflation and current account deficits, especially if they result from expansionary fiscal and monetary policy, will cause investors to lose confidence in the value of a currency. A currency crisis is thus a rational response by investors to the poor condition of the economy or inflationary macroeconomic policy. Others, however, argue that investors can behave like herds of cattle that can stampede at the slightest tremor. If enough investors simply believe that a currency is going to lose its value, others will follow suit, and major sell-off takes place. This could happen regardless of whether governments followed prudent macroeconomic policy or not. Economists thus debate how rational and stable investor behavior is during currency crises.

Against this backdrop of economic theory, some economists have begun to argue that exchange-rate policy is also a key culprit in producing currency crises. In this view, exchange-rate pegs have made developing states prone to speculative attacks and currency crises. Pegged exchange rates are those in which the government mandates a specific value or range of values for the exchange rate, but retains the power to alter the exchange rate at its discretion at any time. Many of the states that suffered in the crises listed above, such as Mexico, Brazil, and Thailand, had pegged exchange rates up until the crisis hit. If the government reserves the right to alter the exchange rate at any time, investors stand to gain or lose substantial amounts if they buy or sell before an alteration in the exchange rate. Investors are thus tempted to place bets on when the next devaluation or revaluation will take place. These bets could reflect either estimates of a government’s macroeconomic policies or the behavior and mood of other investors. As the international capital market grows, these bets grow can larger, even to the point of overwhelming a state’s ability to exchange currency. When a state does not have the reserves of foreign currency to exchange currency at its announced rate, that is a crisis. Policy analysts and other observers have called upon developing states to avoid pegged exchange rates in order to reduce the risk of speculative attacks.2

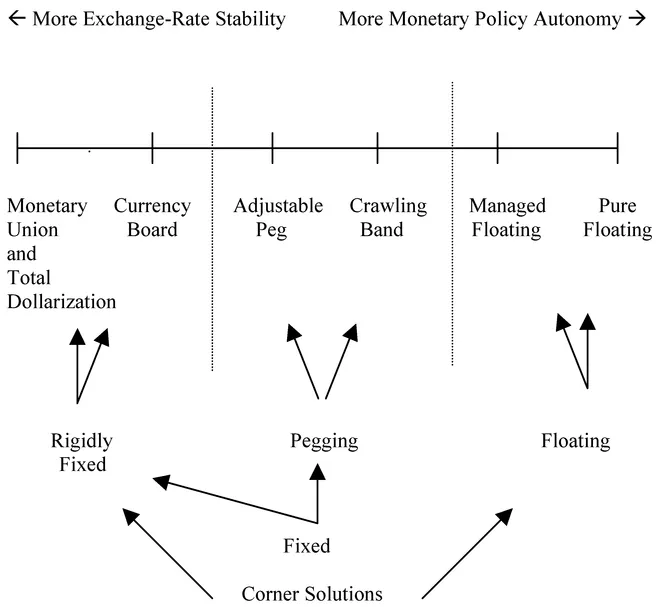

Many economists now argue that the growth of international capital mobility has made it prohibitively costly to maintain exchange-rate pegs. By 1997, investors owned a total of $6 trillion of tradable securities across borders (IMF, 1999a, p. 142). The amount keeps growing, and most of these assets are highly liquid. The growth in electronic computing and telecommunications, the innovation of new financial instruments, and deregulation of financial markets have combined to expand the flow of capital across borders dramatically. A number of economists have argued that the current international environment of mobile capital has made the option of pegging simply unworkable (Eichengreen, 1994; Goldstein, 1995; Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff, 1995; and Fischer, 2001). One, Barry Eichengreen, even predicts that in the future, capital mobility will leave states with no choices but monetary union (in which a country shares a currency with another country) or floating (in which currency markets determine the value of the exchange rate) (Eichengreen, 1994, p. 4-7). Different forms of pegging which lie between the “corner solutions” (Goldstein, 1995, p.9) of monetary union and floating will be “hollowed out” (Eichengreen, 1994, p.6). This contention that high capital mobility will prevent states from pegging their exchange rates is referred to in this book as the “hollowing-out thesis” (HOT).

But some states insisted on pegging their exchange rates in spite of the risks and costs of growing capital mobility. Thailand, Mexico, and Brazil each maintained a pegged exchange rate for years while its exposure to capital flows grew and kept on pegging until a crisis erupted. Meanwhile, other states such as Peru and the Philippines had abandoned pegs many years before. Why should some countries persist in pegging while others were quick to abandon it? Why would some state take longer to abandon pegs than others if the risks are the same for each? Why did some states tempt fate while others did not? These are the central questions for this book. This book will attempt to explain differences in exchange-rate policies and the use of pegging among developing countries.

The interests and lobbying of domestic banks, I contend, explain much of the drive behind maintaining a peg until a crisis erupts. The choice of an exchange-rate regime is thus rooted in politics as much as economics. Banks and commercial firms3 often borrow more from abroad when bank financing is active. If the exchange rate should fall and foreign currency becomes more expensive, external debt becomes harder to repay. An active banking sector has advantages in influencing exchange-rate policy. In countries with financial systems based on bank-credit, banks are critical engines for investment and a banking crisis could cripple the economy. Banking sectors also tend to be more concentrated in such countries, allowing bankers to organize easily to defend their interests. In countries where businesses rely on other sources of financing, private banks are weaker and governments have more opportunity to abandon pegging earlier.

Exchange-rate regimes

Before exploring the theory, what options do governments have in choosing an exchange-rate regime in the first place? The exchange-rate regime (ERR) is the rule for how an exchange rate is valued. An exchange-rate regime is defined by the extent to which either government or market forces determine a country’s exchange rates. A government can choose from any one of a number of exchange-rate regime options, which can be arrayed along a spectrum (see Figure 1.1, next page). Across the spectrum, governments trade-off degrees of exchange-rate stability for control over interest rates and monetary policy. At one end of the spectrum, a government can determine the rate and devise mechanisms for rigidly maintaining that exchange-rate value into the distant future. The primary benefit of this arrangement is that the exchange rate remains stable over time. The government, however, loses control of interest rates and autonomy over monetary policy when capital is mobile. At the other end of the spectrum, a government can let currency markets determine the value of exchange rates at all times, with no government interference. Government has the most autonomy over the money supply and interest rates, but currency markets tend to make the exchange rate fluctuate. In between these polar alternatives are various mixtures of government and market determination of exchange rates, yielding different degrees of exchange-rate stability and monetary policy autonomy.

Figure 1.1 The spectrum of exchange-rate regime choices

At the fixed-rate end of the spectrum is the option of monetary union. Here, countries share a common currency because one or more of the governments involved agreed to do so. The U.S. and Panamanian governments established a monetary union in 1904, which has continued ever since with only one brief interruption (Cohen, 1998, p.174). Panamanians use the U.S. dollar in their daily domestic transactions. Thus, the people of Panama effectively have an exchange rate of one dollar to one dollar.

The next choice along the spectrum is that of a “currency board,” in which a country has a separate currency, but only issues currency at a fixed ratio to reserves of a specific foreign currency that it holds. For example, in Lithuania in the early 1990s, the Bank of Lithuania was charged with the power to issue new currency, but under law it could only issue four new Lithuanian litas for every one U.S. dollar that it could acquire for its reserves (Camard, 1996). In this way, the Bank of Lithuania could guarantee that it will exchange one U.S. dollar for four litas. This choice also provides for exchange-rate stability, as in a monetary union, but government still does not have the autonomy to determine interest rates or the volume of the money supply. It is the equivalent of a monetary union, except that a government has the political symbolism of its own currency and the government can earn interest on its foreign exchange reserves. For the purposes of this book, monetary union and currency boards will together form one of three basic choices for an ERR, called “rigidly fixed exchange rates.”

At the other end of the spectrum are “floating” or “flexible” exchange rates, where the market determines the value of the exchange rate. In a “managed float” currency markets are the main determinant of exchange rates, but the government, at its discretion, may influence the exchange rate by adjusting the money supply to raise or to lower interest rates or exchange rates, or by intervening in currency markets. The government does not necessarily commit itself to an announced exchange-rate target. Many emerging-market countries, such as Indonesia, the Philippines and Bolivia, engage in managed floating. Many floats in developing states seem to be managed floats (Calvo and Reinhart, 2000). In a “pure float,” the government does not attempt to influence the exchange rate at all. A pure float represents the opposite extreme from monetary union. Both forms of floating are the second basic choice for exchange-rate regimes. “Floating” exchange rates in this book refer to both managed and pure floats. As rigidly fixed rates and floating rates represent opposite ends of the spectrum, they shall be referred to as the “corner solutions” to the problem of ERR choice.

“Pegged” exchange rates constitute the choice in the broad middle of the spectrum between rigidly fixed rates at one end and floating rates on the other. Pegged rates involve a claim on the part of the government that it will exchange its currency for another at a specified rate, even though the government may not have the reserves to supply all the foreign currency people might demand, as it necessarily would with a currency board. The exchange rate is an “adjustable peg” in that the government can alter the rate at its discretion at any time.4 The peg value is thus contingent upon the government commitment to that exchange rate, its volume of foreign exchange reserves, and its foreign borrowing capacity. With discretion to alter the exchange rate, governments have more monetary autonomy than in the case of monetary union or a currency board. The more adjustments the government makes to the exchange rate, however, the less stable the rate will be.

Pegging arrangements come in a number of forms, reflecting a number of different considerations. A country may peg its currency to a single currency, as say, Jordan pegs to the U.S. dollar or Lesotho pegs to the South African rand. It could also form a composite index of two or more currencies (called a “basket”) and peg the currency to a specific value of that index, as Morocco does, to accommodate its exchange rate to two or more trading partners. The government could set a specific pegged rate for its currency, or it can let currencies float within a “band” that allows exchange rates some room for maneuver. For example, Saudi Arabia allows its currency to float within plus or minus 7.25 per cent of its assigned value against the dollar. Furthermore, whether a country uses a specific peg or a band, a government may choose to alter the exchange rate at specific, unannounced instances that suit its interest or according to a pre-announced timetable (which would be an “adjustable” peg or band). However, the government may continuously alter the exchange rate according to specific economic indicators such as domestic inflation (called a “crawling” peg or band) in order to adjust the exchange rate to constantly changing economic conditions. Here, all of these variants on adjustable pegs (baskets, bands, and crawls) will be included under the umbrella term “pegging.”5 All forms of pegging are in a sense a “hybrid” or compromise form of ERR, between the polar alternatives of monetary union or currency boards at one extreme or freely floating exchange rates at the other. The composition of currencies in the peg, the amount of wiggle room for the exchange rate, and the timing of alterations in the rate are not the central focus of this book. The research here investigates why states choose pegged exchange rates instead of one of the corner solutions despite a high level of capital mobility.

Capital mobility

Capital mobility refers to the ability of capital to move across national borders. In a world of high capital mobility, currencies and other financial assets can be traded with little problem. In a world of low capital mobility, international investment may incur all sorts of transaction costs, which include brokerage fees, costs for acquiring information, and legal restrictions on capital transactions. Foreign and domestic assets also come with different risks and taxes, which may also reduce incentives for investors to move capital across borders. In the absence of such frictions, perfect capital mobility has the effect of equalizing the price of similar financial assets in different countries. “Financial arbitrage,” where investors profit from differences in prices in different markets, produces this equalizing process. Assume a case in which six-month treasury bonds in two different countries have different rates of return, even after accounting for the expected exchange rate between the two countries. Assume also that the exchange rate is just as likely to appreciate as it is to depreciate, making each investment equally risky. Investors in the country with the lower rate of return would sell their bonds to buy bonds in the country with the higher rate of return. As bonds with the higher rate of return are bought, their price increases, and their rate of return goes down. As bonds with the lower rate of return are sold, their price decreases, and their rate of return rises.

Financial arbitrage helps to explain why capital mobility, which is the ability to trade capital across borders, is not the same thing as capital flows, which are the amount of capital traded across borders (Machlup, et. al, 1972). In the example just given investors stop trading bonds when the rates of return for both bonds are equal given the expected exchange rate. Capital flows for these bonds would cease, even though capital mobility has not changed. Investors are still able to make international transactions, but would not be willing to do so because there would be no further profit in it. In practice though, higher capital mobility is associated with greater capital flows. Capital markets only reach a durable equilibrium if exchange-rate expectations and other investment risks remain constant for long periods, but they almost never do.

Capital flows have undoubtedly grown over the past few decades. In developing countries, net capital investment (both direct and portfolio) as a share of GDP rose from an average of two percent in 1987 to five percent in 1997 (IMF, 1999a, p. 3). The daily turnover in major foreign exchange markets reached $1.88 trillion in 2004, almost triple the daily turnover of $650 billion in 1989 (BIS, 2004, p. 5). As it is more difficult to measure capital mobility, economists are in less agreement as to how much that has grown, if at all. Many commentators today write as if the world has perfect capital mobility. It is probably more accurate to say that while capital mobility is not perfect, it has been growing over the past two decades. Many countries have lifted their controls or restrictions on international capital trading since the 1970s. The recent growth in capital mobility is the result of improvements in trading and settlement practices and computer technology that have lowered transaction costs, as well as efforts by governments to liberalize capital flows and the development of various financial innovations that allow investors to diversify risks more efficiently. Nevertheless, some risks, information costs and capital controls still remain.

Any ERR, such as pegging, that involves a government commitment risks the possibility that the government will not have the international liquidity to meet that commitment. International liquidity includes both the government’s reserves of foreign currency and its capacity for foreign borrowing. The government’s stated exchange rate may generate a demand for foreign currency that outstrips the ability of private agents and the government to supply it, which is an exchange-rate crisis. As capital mobility rises, the potential for demand to outstrip supply increases. Volatile foreign exchange markets are trading ever-larger volumes of currency, beyond the volumes of foreign exchange that governments have on reserve or can raise through borrowing. As recent events have shown, currency crises seem to be becoming more common.

Governments can manage such market pressures with capital controls, higher interest rates, or foreign borrowing (Eichengreen, 1994, pp.66-73), but these are becoming increasing costly as capital mobility increases market pressures. Investors increasingly find wa...