![]()

Part I

Print, Progress and Politeness

![]()

1 Andrew Millar’s ‘Good Vouchers’

The Malt Tax Crisis and Trade in Controversy

Adam Budd

The riot that broke out in Glasgow upon the introduction of duty on malt in Scotland, on 23 June 1725, may have led to the century’s most deadly instance of civil disorder.1 As many as thirty-two people were killed when government troops, led by Captain Bushell, fired live shot at a street protest following the local maltsters’ refusal to allow excise inspectors into their stores.2 Official and unofficial reports describe the killing of bystanders, including ‘a young Gentlewoman looking from a Window, who being just about to be married, had come to Glasgow to provide [for] herself’.3 It is difficult to know the extent to which the many ‘true accounts’ lent theatricality to the rioters and to the soldiers. Reports describe a cross-dressed man beating a drum in the street and a platoon of soldiers arguing whether to break open their own guard house, which neighbourhood women had bolted shut (the troops’ rifles were inside).4 Those who remembered the brutal famines of the 1690s associated the new tax on two dietary staples (ale and therefore bread) with the threat of starvation: some thirty years had passed since the last famine, but population levels remained thirty years away from recovery.5 Scotland suffered poor grain yields in 1723 and 1724, raising the price and lowering the quality of its malt; even the Convention of the Royal Burghs worried that the country could not pay higher prices for these basic dietary staples.6 The personal and political stakes were so high following these disturbances, for civil servants, merchants and local people, that a balanced understanding of the violence that took place in the Trongate probably never will be known. Robert Wodrow, the well-connected ecclesiastical historian in nearby Eastwood, collected reports from different perspectives. Despite their number, Wodrow concluded that most readers were misinformed.7

All reports agree, however, that the newly-sworn Lord Advocate, Duncan Forbes, blamed the violence on the failure of the Glasgow magistrates to prevent rioters from ransacking the Palladian mansion belonging to their MP, Daniel Campbell, a supporter of the tax.8 But this riot was not a revolt against what E. P. Thompson has described as ‘the moral economy’, though some had remarked that the new tax was a clear breach of the Treaty of Union.9 Unlike the excise man in Robert Burns’s ballad, the excise officers in Glasgow were not threatened by anyone.10 It seems clear that the rioters were expressing desperation over the infuriating prospect of starving while their own parliamentary representative enjoyed ostentatious wealth. The recent election of Charles Miller as Lord Provost of Glasgow ‘turned out of office [Daniel] Campbell’s friends who had monopolized the government of the city for years’, which suggests that local merchants were frustrated too.11 Daniel Campbell was the ‘unofficial banker’ of Archibald Campbell, then Earl of Ilay, and he had dominated Glasgow politics on behalf of Ilay and his brother, the second Duke of Argyll, since 1706.12 The riot gave a fine opportunity for Forbes, ‘a certain lawyer giddy with his new preferment’, to demonstrate the Duke of Argyll’s authority in Glasgow.13 Forbes himself had owed his seat in Parliament and his legal appointment to Argyll: so when he ordered the arrest of Glasgow’s civil magistrates, he took revenge on the very men who had challenged his patron’s influence.14 Interestingly, none of the surviving archival documents mention that the new Provost was connected with Glasgow’s Incorporation of Maltmen, which supported the protests.15 Finding empirical evidence of the magistrates’ involvement in the violence was not, evidently, Forbes’s concern.

Figure 1.1 Robert Paul, Foulis Academy, 1770, Trongate in 1750.

Figure 1.2 T. Fairbairn, watercolour, 1894.

Forbes ordered Charles Miller’s arrest, along with five of his fellow councillors, directing soldiers to place their wrists in shackles and commit them to their own tollbooth for having ‘favoured and encouraged the Mobs’.16 He then imposed a humiliating military occupation on the town, commanded by Sir Duncan Campbell, who was none other than Daniel Campbell’s godson.17 One pamphlet likened this treatment to the notorious ‘Bloodbath of Thorn’ during the previous summer, when nine Polish Lutherans were put to death on the orders of Catholic authorities.18 These actions exposed distinct loyalties, clarified individual obligations and led to a campaign of censorship and media protest whose legacy would be felt many decades later.

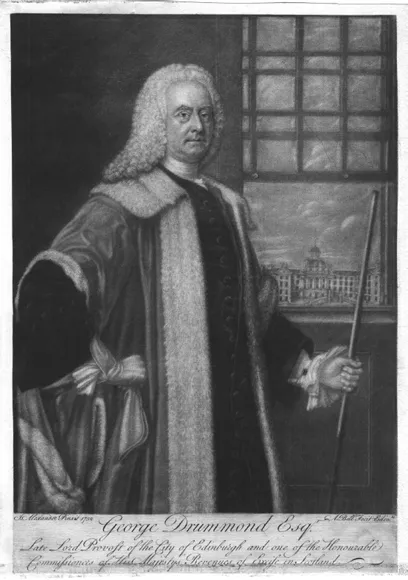

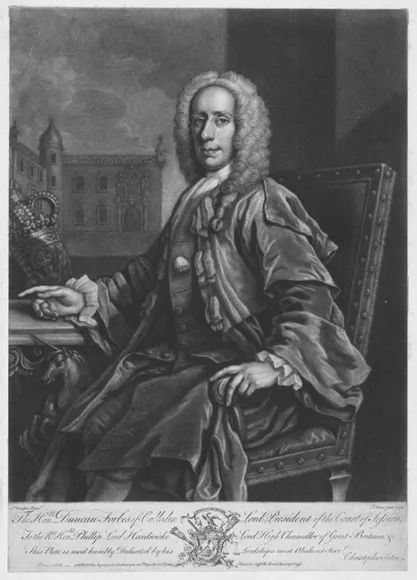

The Lord Advocate also directed magistrates on the Edinburgh Town Council to exert their legal control over two local newspapers, the only regular papers in the country.19 Commentators in both towns understood that the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, John Campbell, was Daniel Campbell’s older brother;20 and that the Dean of Guild, George Drummond, planned to run for the Provost’s chair later in the year.21 By dictating a false report from Glasgow to the Caledonian Mercury and seeking to do the same to the Edinburgh Evening Courant, Forbes tried to shape perceptions on a national scale.22 This displayed a striking degree of corruption and arbitrary use of force on the part of Forbes and his client on the Council, Drummond.

Over the years that followed, citizens and historians described Duncan Forbes and George Drummond as leading figures of cultural improvement during the Scottish Enlightenment. Forbes served for ten years as Lord President of the Court of Session, the highest judicial office in Scotland, and Drummond served six terms as Lord Provost of Edinburgh.23 By the time of Forbes’s death in 1747, as Lord Advocate he was remembered for his ‘sweetness and compassion worthy of a chief and principal servant of so mild a King: No man was more willing than he to bring villainy to light, and none so ready to protect and defend the innocent’.24 Both men were celebrated in portraiture, public monuments and folio prints for domestic consumption, immortalizing their civic stations and political offices.25 Today, the History of Parliament emphasizes Forbes’s sympathetic advocacy on behalf of Jacobites who were mistreated following the Fifteen, and the clemency he sought for those who forfeited their estates following the Forty-Five.26

We should understand this as a considerable rehabilitation from Forbes’s reputation in Glasgow upon assuming his position as the Crown’s chief legal representative in Scotland. To ensure that Forbes’s humiliation of the Glasgow magistrates extended to the people, he insulted local witnesses with a telling line of questioning:

he was pleased sometimes to condescend so far as to be very merry, insomuch that he ask’d the Town-Clerk, if he could write? … and if ever they heard any body curse or reproach Mr Campbell, whose House was pillaged? And if they believed in their Conscience, that the Mob was designedly raised to hinder the levying the Malt Tax?27

Forbes had made these arrests without procuring a warrant from the Justice Clerk of the Lords of Session, who oversaw all criminal investigations in Scotland, nor had he received permission or instructions from London.28 It was this conduct for which Ilay described Forbes as ‘very violent’, and for which the advocate Robert Dundas sought an order of sederunt, to release the Glasgow magistrates.29 The fact that they were released by the Lords of the Judiciary, immediately upon their arrival in Edinburgh for trial, only emphasized the injustice among their correspondents in Glasgow and the public in Edinburgh. It was these same judges who had offered bail to the magistrates when they were first imprisoned in Glasgow, but Forbes had overruled their decision.30 Speaking in Parliament the following year, Forbes ‘laid all the blame on the Lords of the Session and magistrates of Glasgow’ for the rioting and the violence.31 The following year, Daniel Campbell succeeded in his demand that Parliament extract £6,080 from the town to cover the damages to his house, which was 50% more than he had paid to build it.32 When a bill of indictment was sent to the Solicitor General, accusing Captain Bushell of murder, the Lords of the Judiciary granted Bushell and his officers a full pardon. This forbade legal investigation of the violence, bringing the case to a close.33

Figure 1.3 George Drummond, by Miss A. Bell, after J. Alexander, 1846. 13 × 9 in. Mezzotint.

Figure 1.4 Duncan Forbes of Culloden, Mezzotint, 1748. 14 × 10 in.