![]()

PART I

How We Got Here

![]()

CHAPTER 1

WHICH CAPITALISM?

Why would someone like the late Stephen Hawking, the renowned theoretical physicist at the University of Cambridge, have regarded Western capitalism and its untamed freedom as far more dangerous to the future of humanity than quantum particles, robots, and aliens combined?1 Coming from such a penetrating mind, this judgment on what appears to be the engine of unparalleled prosperity suggests there must be a serious intellectual enigma at the heart of capitalism.

The Capitalist Enigma

“Capitalism” is one of those big concepts concocted by their enemies—in this case, named as such by its chief antagonist, Karl Marx, in his definitive book on the subject, Das Kapital. Even the supporters of capitalism cannot agree on what its essence is, or when it began. Marx targeted the fourteenth century as the end of feudalism and the beginning of the capitalist stage of history. Others point to the Renaissance (fifteenth century), the Reformation (sixteenth century), the Enlightenment (seventeenth century), or even the start of the Industrial Revolution (eighteenth century).

Marx’s timeline has capitalism emerging from a long feudal conflict between lord and serf that ended with owners of capital exploiting workers in the modern era. Though intrigued by capitalism’s longevity, Marx was still certain it would fall. But he described the rise of capitalism in a surprisingly positive way, noting that “serfdom had practically disappeared” in England by the late fourteenth century. “The immense majority of the population consisted then and, to a still larger extent in the fifteenth century, of free peasant proprietors, whatever was the feudal title under which their right of property was hidden.”2 The fact that serfs had wrested more and more control over their own labor from lords allowed new capitalists to attract the freed labor and create “more massive and colossal productive forces than have all previous generations together.”3

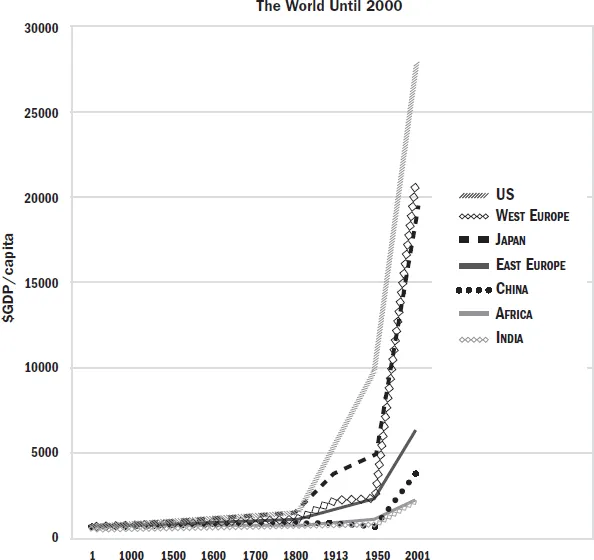

Little systematic data has been available to document when capitalist productivity first emerged or why. Angus Maddison’s study for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Historical Statistics for the World Economy, collected the best data available for examining the question empirically.4 Tom G. Palmer used this data to locate “the sudden and sustained increase in income” that marked Europe’s capitalist takeoff above the rest of the world. His analysis of Maddison’s data points to “around the middle of the eighteenth century” as the beginning of the takeoff that produced capitalism. The change is illustrated dramatically in a chart beginning with year 1 of the Common Era.5

The big spike in wealth per capita appears first in western Europe in the years around 1800, as Palmer claimed, but even more dramatic is the rise of the upstart United States a few years later, shooting past its mother country and all of its European rivals to new heights of wealth. By World War I, eastern Europe began its takeoff, followed by Japan, although both of these remained well behind the United States and western Europe. India, China, and Africa begin rising in the 1950s, but today remain well below what the U.S. had attained in 1900.

Because of this timeline, Palmer credited Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) and his classical liberalism generally as the source of capitalism, market freedom, and modern prosperity. Yet the man who did perhaps the most to revive capitalism and classical liberalism in modern times, F. A. Hayek, had stated in The Constitution of Liberty, in 1960, that the origins of liberal capitalism, and especially the central idea of the rule of law, lay in the Middle Ages.6 In fact, Palmer acknowledged that it took time to build the necessary “legal orders characterized by well-defined, legally secure, and transferable property rights, with strong limitations on predatory behavior,” and these originated long before the eighteenth century.7

In Suicide of the West, Jonah Goldberg likewise identified the eighteenth century as the turning point. “For 100,000 years, the great mass of humanity languished in poverty,” with innovation stifled by authorities, and then something “miraculous” happened and changed everything. What Goldberg called “the Miracle” occurred spontaneously in the 1700s with the emergence of a middle-class ideology of “merit, industriousness, innovation, contracts, and rights,” which produced “the most cooperative system ever created for the peaceful improvement of peoples’ lives.” He even asserted that “nearly all of human progress has taken place in the last three hundred years.” Yet he went on to clarify that his review of history showed the eighteenth-century Miracle to be “the climax of a very long story.”8

Niall Ferguson, in Civilization: The West and the Rest, linked the takeoff with the invention of the printing press, which facilitated communication and trade, and with the sixteenth-century Reformation and the resulting competition between religious institutions. He found the “path to the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment” to have been “long and tortuous,” however, and saw it beginning in “the fundamental Christian tenet that church and state should be separate.” He specifically mentioned the importance of St. Augustine’s theology and of the investiture crisis during the papacy of Gregory VII in the eleventh century.9

In How the West Grew Rich, Nathan Rosenberg and L. E. Birdzell traced the beginnings of the legal order underlying capitalism to the thirteenth century or before.10 Christopher Dyer, in An Age of Transition: Economy and Society in the Later Middle Ages, identified the critical period for the emergence of capitalism as the twelfth century, although he also pointed to earlier foundations.11 In The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages, Jean Gimpel attributed the Western growth in population and wealth partly to the use of water-powered mills, recorded in England as early as the Domesday Book of 1086, and later used heavily by Cistercian monasteries, which also developed scientific agricultural practices in the twelfth century. Banking institutions originated in Italy during the same period.12

Harold Berman, in Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition, meticulously traced the crucial legal and moral developments back to the Abbey of Cluny (founded in 909) and to the reforms of Pope Gregory VII, who had been a monk in a Cluniac monastery. The many Cluniac foundations across Europe were governed through an innovative corporate structure under the abbot of Cluny, which enabled Gregory VII to reassert the independence of the church from secular powers, particularly in his conflict with Henry IV, the Holy Roman Emperor. As Berman’s comprehensive study suggests, the history of capitalism is simultaneously the history of Western civilization.13

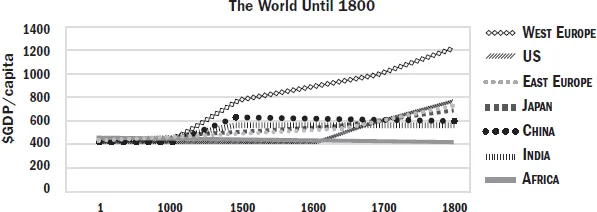

Data from the OECD can help settle the matter of when the capitalist takeoff began. Michael Cembalest of JP Morgan and Derek Thompson of the Atlantic used this data to plot GDP for various parts of the world over nearly two millennia up to the year 1800, as shown in the chart above.14

This data, the best available, suggests that the economic takeoff of western Europe actually originated as far back as the tenth or eleventh century. In the Palmer chart, this early beginning is obscured by the compressed scale, but still visible. Another distinct uptick appears in the sixteenth century, followed by a more obvious increase in the rate of growth in the eighteenth century, leading up to the dramatic takeoff in Europe and the United States emphasized by Palmer and others, including Deirdre McCloskey.15

Many scholars reject the idea of a medieval takeoff as a myth. Palmer attributes the idea to a “common yearning for a past ‘golden age,’ a yearning that is still with us.” He aligns himself with the classical liberals who “have persistently worked to debunk the false image of the past—common to socialists and conservatives alike, in which happy peasants gamboled on the village green, life was tranquil and unstressed, and each peasant family enjoyed a snug little cottage.”16

Yet the medieval era is more often labeled a dark age rather than a golden one. It was Renaissance classicists who first described the era preceding their own time as benighted—discounting the real accomplishments of medieval thinkers and inventors. Reformation theologians could not have made a case for reforming what was not dark and decadent, and Catholic intellectuals wished to leave the past behind once they had embarked on their modernizing Counter-Reformation. Later, Voltaire could not have proclaimed a new age of “enlightenment” if what came before had not been an age of ignorance. From the fifteenth century to the twentieth, there was little interest in seeing an inventive and prosperous Middle Ages.17 Yet the best scholarship points to the Middle Ages in Europe as the launching pad for the Western economic takeoff.

The empirical Index of Economic Freedom compiled by the Wall Street Journal and the Heritage Foundation shows that the legacy of those medieval roots is still visible in the global economic map. Of the thirty-seven nations rated “free” or “mostly free” in the 2020 ranking, nineteen are European or, like the United States, are former colonies with a predominantly European culture and population. Even among the eighteen non-European nations, most were European colonies or protectorates for a substantial period of time—Hong Kong for a century. Mauritius was unpopulated until occupied by the Portuguese and the Dutch. Japan did not achieve widespread prosperity and freedom until after U.S. occupation. Taiwan was not under direct European control before achieving economic freedom and prosperity, but its free-market reformers were Western-inspired. The others are all very recent additions to the top two categories.18

The columnist Fareed Zakaria disputed the connection between prosperity and culture, arguing that although “the key driver for economic growth has been the adoption of capitalism and its related institutions and policies,” it has taken place “across diverse cultures,” including India and China.19 But as the charts demonstrate, they lag behind the West economically, and both are rated “mostly unfree” on the worldwide economic freedom list—India in 120th place and China at number 103. Yes, they have seen considerable growth as they have adopted some market reforms, but they are still mainly poor and not very free. Hong Kong’s capitalism is straining under mainland Chinese control. Singapore has only a quasi-free political system, threatened by conflict between Chinese, Malay, and Muslim inhabitants. Bahrain was ranked eighteenth on the economic freedom list in 2016, and its economy had many market elements that allowed it to prosper, but it is a centralized Sunni monarchy that was forced to call in Saudi troops in 2011 to quell a restive Shia-majority popular uprising, and was ranked 63rd in 2020.

Top-ranked Singapore and Hong Kong might have appeared to support the idea that economic prosperity doesn’t depend on broader political and cultural forms. But how comfortable can one be that non-Western nations now rated relatively free economically can remain so? After all, Mali was once rated mostly free but now it is “mostly unfree,” at number 126. If current prosperity can be ascribed to the adoption of scientific materialism, skeptical rationalism, or even classical liberalism, then it might be possible to create a formula that will build and sustain a capitalist system. But if deeper beliefs and attitudes, customs and social institutions are essential, capitalism beyond the West is extremely problematic—a point made convincingly by Svetozar Pejovich in Law, Informal Rules and Economic Performance.20

Note that Zakaria’s statement quoted above has a major qualification: it was not only accepting capitalism that was essential, but also adopting Western civilization’s “related institutions,” the ones that took centuries to develop before capitalism could take root, as Hayek and the others found. Western nations themselves may not be able to sustain capitalism without these traditional institutions. Italians once led Europe in economic development, but modern Italy has recently ranked only 74th on the Index of Economic Freedom and showed a growth rate of only 1.6 percent. In the past few years, the Index has excluded the United States from its highest “free” category because of restrictions on contract rights in the bailouts of banks, Chrysler, and GM in 2008.

So in pointing to the feudal age, Marx identified the roots of the capitalist civilization more accurately than many of its defenders. Might he likewise be a better prophet? While his economic predictions seem far off the mark, his cultural findings resonate today. Marx found that capitalism had “put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations” by the mid-nineteenth century.

It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his “natural superiors,” and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callus “cash payment.” It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervor, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism in the icy water of egotistical calculation.…It has stripped of its halo every occupation … torn away from the family its sentimental veil.… All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.21

As we have seen, the great economic historian Joseph Schumpeter predicted that capitalism, even with all its freedoms and with the market’s efficient calculation and allocation, could not survive much longer without the moral values and cultural institutions that had nurtured and sustained it. Indeed, he raised the possibility that capitalism may be better classified as the final stage of feudalism than as a separate stage of history. As the medieval morality has faded,...