1

Certus

When he first began to publish poems, Seamus Heaney’s chosen pseudonym was ‘Incertus’, meaning ‘not sure of himself’. Characteristically, this was a subtle irony. While he referred in later years to a ‘residual Incertus’ inside himself, his early prominence was based on a sure-footed sense of his own direction, an energetic ambition, and his own formidable poetic strengths. It was also based on a respect for his readers which won their trust. ‘Poetry’s special status among the literary arts’, he suggested in a celebrated lecture, ‘derives from the audience’s readiness to … credit the poet with a power to open unexpected and unedited communications between our nature and the nature of the reality we inhabit’. Like T. S. Eliot, a constant if oblique presence in his writing life, he prized gaining access to ‘the auditory imagination’ and what it opened up: ‘a feeling for syllable and rhythm, penetrating far below the levels of conscious thought and feeling, invigorating every word’. His readers felt they shared in this.

The external signs of Heaney’s inner certainty of direction, coupled with his charisma, style, and accessibility, could arouse resentment among grievance-burdened critics, or poets who met less success than they believed themselves to deserve. He overcame this, and other obstacles, with what has been called his ‘extemporaneous eloquence’ and by determinedly avoiding pretentiousness: he possessed what he called, referring to Robert Lowell, ‘the rooted normality of the major talent’. At the same time, he looked like nobody else, and he sounded like nobody else. A Heaney poem carried its maker’s name on the blade, and often it cut straight to the bone.

Fame came to him young, but when necessary, Heaney practised evasiveness, like the outlaws on the run who regularly inhabit his work, or the mad King Sweeney of Irish legend, condemned to live the life of a migrant bird, whom he chose as an alter ego. This literally came with his territory. He was born in Northern Ireland in 1939, grew up among the nods, winks, and repressions of a deeply divided society, and saw those half-concealed fissures break open into violence. He knew ‘the North’ (as residents of the Irish Republic call the six north-eastern counties), targeted it, eviscerated it, and left it to live in ‘the South’. It gave him the title of his most famous collection, and he showed how ‘it’ could be written about. But the restraint which he generally practised when addressing politics, coupled with the spectacular internationalising and cosmopolitanising of his reputation, raised sensitive questions. If ‘Sweeney’ rhymed significantly with ‘Heaney’, ‘famous’ rhymed too readily with ‘Seamus’.

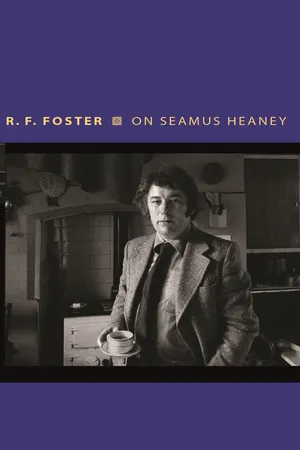

He was endlessly photographed and painted, but the portrait in oils by Edward McGuire commissioned by the Ulster Museum in 1973 is perhaps the most enduring image: ‘the poet vigilant’, in Heaney’s own description, expressing a ‘gathered-up, pent-up, head-on quality … a keep of tension’. The powerful, handsome head is placed against a densely interwoven thicket of leaves, suggesting the concealed bird-king or the watchful wood-kerne—but also, perhaps, the double-f repeat pattern of a Faber book cover. It is a complex picture of a poet whose complexities stretch far beyond the charm of his early poems—a charm which itself is never simply what it seems.

Seamus Heaney’s background has been immortalised in those poems as well as a large archive of interviews: a small Derry farmhouse, a cattle-dealing father, a much-loved mother and aunt presiding jointly over the domestic world; the routines of beasts, crops, and land; horses and carts, candles and oil lamps, an outdoor privy, mice scrabbling in the thatch above the children’s beds at night, a world already becoming archaic in his youth. (Smart alecks in Dublin used to refer to these poems, and their author, as ‘pre-electric’.) There is a Proustian exactness in his evocation of the texture and detail of his early life, the unerring memory for the illustration on a tin of condiments or the name of an obscure piece of machinery, and he retained a novelist’s perception of circumstance and psychology. He could also mock this aspect of his reputation: on a visit to the ‘Tam O’Shanter Experience’ at Robert Burns’s birthplace, he was teased that there would one day be a ‘Seamus Heaney Experience’ and replied, ‘That’s right. It’ll be a few churns and a confessional box’. Heaney was marked out early by his cleverness (in a family with its fair share of schoolteachers as well as farmers, and giving the traditional Irish priority to a good education). He progressed from the local primary schools, via success in the eleven-plus examination, to life as a boarder in St Columb’s College, Derry. The wrench of leaving home and family at twelve years old in 1951 remained a sharp memory; the poems and autobiographical reminiscences which record it suggest the special position which he held in his family.

‘I began as a poet’, Heaney later remarked, ‘when my roots were crossed with my reading’. At St Columb’s, his classmates included the future politician John Hume and the brilliant Seamus Deane, himself an apprentice poet but better known later as a powerful and excoriating literary critic. From early on, they would try out their poetic efforts on each other. The College’s conventional but thorough education gave a good grounding in Latin, which served Heaney well in later life, but also exposure to the English poetic tradition (discovery of Patrick Kavanagh’s work, which would mean so much to him, came later). The intensive interviews to which Heaney was subjected later in life, particularly those in Dennis O’Driscoll’s indispensable Stepping Stones, supply the framework for his emergence as a poet. ‘Just by answering’, Heaney himself remarked ruefully, ‘you contribute to the creation of a narrative’. Here as elsewhere, he was adept at controlling his fame.

His first poetic passion was Gerard Manley Hopkins, as is evinced in the lush and winsome wordplay of early poems submitted to local magazines during his time at Queen’s University Belfast (1957–61), which rightly remained uncollected. The lushness was eradicated fairly soon, in obedience to his mentor Philip Hobsbaum’s injunction to ‘roughen up’; winsomeness continued to break out now and then. From Queen’s, he proceeded to train as a schoolteacher, and rapidly attracted attention; the Inspector of Schools decided to haul him out of the schools and appoint him Lecturer in English at St Joseph’s College of Education ‘to teach the other teachers how to teach … he’s as good a teacher as he is a poet’. This remained true, at several levels, all his life. It is illustrated by notes he made around this time for an anthology of poetry to be used for teaching purposes. His approach stresses the need to explore a poem’s nature rather than simply evaluate it in terms of practical criticism, to address process rather than product, to intuit the direction of the poet’s mind, and to map the hinterland behind a finished work; Hardy, Yeats, Lawrence, Kavanagh, MacNeice, Muir, Lowell, and Wilbur would feature. The anthology remained uncollected, but an academic life seemed on the cards. He had thoughts of writing a thesis on ‘the repressed hero in modern Irish writing’, but no-one in Queen’s seemed interested in supervising it; he began an uncompleted thesis on Patrick Kavanagh, introduced to his work by the short-story writer Michael McLaverty, a colleague, mentor, and friend during his school-teaching days. And in 1966, Heaney joined the Faculty of English at Queen’s University, a step up the academic ladder.

The cultural atmosphere of Belfast in the early 1960s is hard to recapture. Given what happened from 1968–9, when communal violence broke out, the British Army moved in, and three decades of murderous conflict commenced, images of a calm before a storm are inescapable. But it did not always seem like that at the time. Patterns of sectarian discrimination ran deep and were carefully negotiated; the representatives of state power were blatantly and often oppressively Protestant; the underside of violence sometimes broke through (as captured chillingly in a 1964 short story by the poet John Montague, ‘The Cry’). Much recent analysis, however, has represented life in Northern Ireland (particularly middle-class life) in the early 1960s in terms of the thawing of antagonisms and the hesitant beginnings of a more pluralist culture. Heaney’s own recollections are not inconsistent with this. But even if the advent of apocalypse after 1968 is seen as an avoidable lurch into violence rather than the inevitable bursting of a boil, it fed on ancient antipathies as well as recent injustices.

In some senses, the Queen’s University of the 1960s was at an angle to this universe. It certainly represented the Unionist governing class, and it was seen by some as a kind of colonial outpost. A large proportion of its teaching staff were British, and many returned to ‘the mainland’ when teaching terms were over. But this detachment, while accompanied by a fair amount of condescension sharply noted by the locals, helped insulate the Queen’s common-room life from more atavistic attitudes, as Heaney himself recalled. At the same time, the underlying realities of his native province were grist to his mill. A poem called ‘Lint Water’ was published in the Times Literary Supplement on 5 August 1965, though not reprinted in his first collection, Death of a Naturalist, a year later (nor anywhere else). The quintessential Ulster industry of linen-making provided a metaphor for the poisoning of running water; Northern Irish readers would be well aware that historically, linen making was notably sectarian in its work patterns. ‘Putrid currents floated trout to the loch, / Their bellies white as linen tablecloths’.

The idea of a poisoned terrain (also used by John Montague for his landmark collection, Poisoned Lands, in 1961) was both irresistible and significant. So is the powerful authorial stamp carried by the poem, which signals the way that Heaney would choose to approach and unpick the tensions of his native province. His own family’s relations with neighbouring Protestant farmers were amicable and equable; there was a sense of difference rather than superiority or exploitation. (With Unionist grandees such as the Chichester-Clark family in the neighbouring Big House, Moyola Park, the gap would be much wider and more definitive, both socially and politically.) Heaney’s father, according to his son, possessed the cattle-dealer’s wide franchise of moving easily through different circles of rural life, while his mother retained a stronger sense of historic grievance.

The poems which Heaney was planting out in Irish newspapers and magazines in the early 1960s made him a name to watch; a cyclostyled sheet of a poetry reading around 1963–4, including several of his first published poems, records him as ‘Seamus Heine’, which may or may not be a joke. But he was one of an extraordinarily talented group of Belfast-based writers who assembled to discuss their work under the aegis of the academic and poet Philip Hobsbaum, from 1963. They included the playwright Stewart Parker, the novelist and short-story writer Bernard McLaverty, the critic Edna Longley, and the poets Michael Longley, Joan Newmann, and James Simmons. Later commentators have queried the extent to which these writers formed a self-defining ‘Group’, and so have some of the writers themselves. But studies by Heather Clark and others suggest an undeniable esprit de corps, if not of joint endeavour, at the time. There was certainly a remarkable ‘coincidence of talent’, in Michael Longley’s phrase, and a practice—as Heaney put it—of ‘doing committee work’ on each other’s poems. This much-mythologised ‘Group’ was undeniably important to Heaney’s poetic development, but so were other poets then based or partly based in Northern Ireland such as John Hewitt, Derek Mahon, and John Montague, the painters Terry Flanagan and Colin Middleton, and the musician David Hammond. Longley, Mahon, and Heaney would become the great triumvirate of Northern poets, with Montague their bridge to an older generation; members of a formidably accomplished younger generation would follow in their wake, such as Tom Paulin, Paul Muldoon, and Ciaran Carson. Between their elders, an inevitable rivalry was maintained, but there was also a certain difference of influence and ethos. Queen’s kept Heaney and his school friend Deane within the Northern habitus (though it was praise from the South African poet Laurence Lerner, then on the faculty, that helped spur Heaney towards the literary life). In a later barbed reminiscence, Deane recalled that when he and Heaney discussed their own writing, they adhered to given roles: Deane excitingly experimental, Heaney imitative, modest, and careful. This memory reflected divergences on several levels over the intervening decades. But more generously, Deane also recalled his realisation that Heaney’s precision was the mark of someone who was writing poems rather than (as in his own case) attempting ‘poetry’.

Other kinds of difference can be charted too. Both of the Longleys and Derek M...