1

Industrial Decline and the Rise of the Suburbs

In June 1962, Nick Poulos, a reporter with the Chicago Tribune, argued that Chicagoland led “by a whopping margin all other regional complexes in the country in industrial development.” Poulos was not alone in his reading of the trends of industrial investment and employment growth since the end of World War II. In 1957, Thomas Coulter, the chief executive officer of the Chicago Association of Commerce and Industry (CACI), wrote that there had been “unprecedented industrial expansion in the Chicago Metropolitan Area during the past five years” and that the organization expected “even more growth in the next five years in the metropolitan area.”1 Similar pronouncements on the region’s postwar industrial growth vigorously promoted a rosy image of manufacturing health. In 1965, the Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission forecast that industrial employment in the Chicagoland area would reach 1.1 million by 1985.

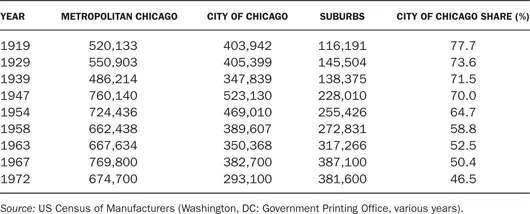

The problem with these rosy pronouncements was that these commentators were ignoring the systematic decline of the city’s manufacturing base. The US census provides the basic outline of the story. The city of Chicago lost 173,000 manufacturing jobs between 1945 and 1963 (table 1.1). The optimism of Poulos and others was misplaced. Industrial decline in the city of Chicago can be dated to the end of the 1920s, with the collapse of the growth cycle centered on the rise of the corporation as the main business organization and the rise of steel, chemicals, electrical appliances, and machinery as the period’s growth industries.2

One result of this process was the spatial reconfiguration of manufacturing investment at both the metropolitan and regional levels as firms began to rethink their geographies of production and to search for alternate investment sites. The interwar reconfiguration was preceded by an earlier pattern that emerged after 1880, which featured the simultaneous building up of the central city and the suburbs but was dominated by the central city.3 The interwar changes were predicated on the relative decline of the city and the rise of the suburbs as the preeminent location for industrial production and employment. The deindustrialization that many identify as starting in the 1970s was simply the outcome of a process that dates back to the breakdown of an old system of industrial organization in the interwar period, the poorly directed affairs of wartime mobilization, and the shift of production to the suburbs in the immediate postwar period.

TABLE 1.1Manufacturing employment in metropolitan Chicago, 1919–72

Industrial decline was not uniformly distributed across Chicagoland before the 1970s. From the 1920s, there are two main patterns: the relative and absolute decline of the city and the continued and rapid growth of the suburbs.4 In whatever way it is measured—number of firms, employment growth, or factory construction—the city experienced incremental decline, while the suburbs took over as the metropolitan area’s premier location of new production space, especially after the end of World War II. To suggest that industrial decline in the city of Chicago has a long history is not to argue there was absolute decline in manufacturing employment in the metropolitan area before World War II, although there were fewer industrial workers in Chicagoland in 1939 than there were in 1919 and 1929.5 Rather, it is to argue that the roots of the devastation unleashed by the deindustrialization of the 1970s had been planted in the city before World War II.

Decentralization in Chicago

In 1942, a Chicago Plan Commission (CPC) report noted that a major problem facing the city was “the trend toward decentralization of Chicago industries to adjacent and nearby suburbs.”6 The CPC report was not the first to identify this issue. In 1915, the Chicago reformer Graham Taylor pointed out that “huge industrial plants” were “uprooting themselves…. With households, small stores, saloons, lodges, churches, schools clinging to them like living tendrils, they set themselves down ten miles away in the open.”7 Using more mundane language, the economist William Mitchell wrote in 1933 that “industrial displacements as have occurred in the region since 1920 have been in the direction not of increased industrial concentration within the city proper,” but in the areas “immediately surrounding the urban nucleus.” This change was not solely due to the expansion of noncity manufacturing units.8 Firms were also leaving the city for the suburbs.

A similar point was made in the 1920s in several articles by Scrutator, a pseudonymous Chicago Tribune journalist. On the eve of the Great Depression, he wrote that firms had “been reaching towards the boundaries of the switching district” forty miles outside downtown Chicago.9 He reported on a speech in March 1929 given by James Cunningham, the president of the Illinois Manufacturers’ Association, who said that “the tendency” at that point was “to spread out,” which meant that the “industrial growth of the great cities” was “retarded.”10 Scrutator added the caveat that suburbs can be inefficient compared to the “great cities,” which are “markets as well as centers of productive industry.” While “some industries might profit by such a removal, others might not.”11 Nevertheless, evidence from studies made by the Middle West Utilities Company showed that city growth “after a certain point of saturation creates more handicaps than facilities for productive industries.”12 As noted in 1924, “industrial decentralization” was “passing from theory to fact” as firms moved to the suburbs to escape high land values, congestion, and labor strife.13 Scrutator and the other commentators were pointing to a shift in the balance of city and suburban employment and the associated restructuring of the region’s industry that would have enormous implications for the local economy over the next fifty years.

The situation was more extreme than these writers realized. Between 1879 and 1919, more than 430,000 new manufacturing jobs were created in Chicagoland.14 Of these, 75 percent were to be found in the city, while the remainder was located in the suburbs. Including the suburban areas annexed by the city, it is evident that the city of Chicago was the major generator of industrial employment up to World War I.15 This changed after World War II, as the city’s dominance of the region’s industrial employment waned. The city’s share of Chicagoland’s jobs declined to only half by 1967 (table 1.1). As Scrutator and others had pointed out, the city’s industrial supremacy was under attack by the 1920s, as corporate executives searched for cheaper production sites. The city lost an absolute number of industrial jobs in the interwar period and after the end of the war.

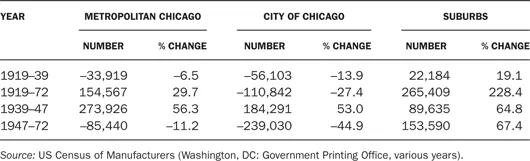

The decline during these two periods was not insignificant. In contrast to the suburbs, which gained industrial workers during the interwar years, the city lost 14 percent of its industrial base over this period (table 1.2). A 1942 CPC report showed that industrial suburbanization was sharply curtailed during the depression, but restarted after 1935. Even after the employment gains from incoming firms, the city still had a net loss of four thousand jobs in the last years of the 1930s.16 The shifting balance of industrial work associated with the deindustrialization of the central city was a long time in the making; it did not just appear with the end of the “postwar glory days” in the 1970s.

TABLE 1.2Manufacturing employment change for selected years, 1919–72

The city of Chicago’s declining share of employment was a direct result of the establishment of factories in the areas ringing the city. One Chicago Tribune reporter noted in 1940 that “within recent years factories [had] moved farther and farther away from the center of the city.”17 Along with a number of older satellite cities such as Elgin and Joliet, the city declined relative to the rest of Chicagoland. Industrial growth increased dramatically in an assortment of suburbs, including Cicero, East Chicago, and Gary. Much of this growth came from arrivals: “the number of industries moving outward from Chicago” was “particularly pronounced in the suburbs immediately outside the city limits.”18 Just as Scrutator had argued a decade earlier, city companies were looking for cheaper land, lower taxes, more docile labor, and the opportunity to install modern production systems in new factories. Even in those cases where central-city factories were not closed, corporations tended to invest more heavily in greenfield sites in the suburbs and other parts of the country. At the same time that firms were leaving for the greener pastures of the suburb, an insufficient number of firms were moving into the central areas to compensate for this loss.

This was the point that Irving Salomon, president of Royal Metal Manufacturing, was making in 1928 when he outlined the reasons why his furniture wire firm set up a branch plant outside the city. A few years earlier, it had started up a new product line at its South Side metal furniture factory. While this gave the company greater markets, it created problems for factory operations because of overcrowding, handling system inefficiencies, and high overhead costs. By the early 1920s, these diseconomies forced company executives to make a decision about location. As they saw it, Chicago had many advantages—transportation, labor supply, local market, and specialized services—which they did not want to give up. But small towns also had advantages, most notably lower property prices and labor costs. Royal Metal executives chose to take advantage of both, taking some of the company’s Chicago workers to Michigan City, Indiana, while moving to a larger factory space on the city’s Lower West Side. By staying in Chicago, the firm was able to reap the design and supply benefits that came with being in the United States’ furniture capital. By hiving off the run-of-the-mill operations to a factory in Michigan City, the firm was able to reduce its freight and labor charges in a plant “designed to give us the greatest possible efficiency.”19

As the Royal Metal case suggests, the changing geography of industrial employment was an outcome of the two aspects of the political economy of place. First, the investment patterns affecting Chicago were greatly determined by industrial decision makers who had a regional or national gaze. In the case of Royal Metal, there were distinct advantages to moving production out of Chicago. At the same time, large multiunit corporations with a national focus came to play an increasingly larger role in the Chicago’s economy, as they did in Trenton, Philadelphia, and elsewhere.20 In Chicago, the rise of oligopolies in steel, meatpacking, transportation equipment, and other sectors gave significant control over the local economy to absentee owners with little interest in Chicago’s industrial, political, and social affairs.21 Investment decisions about installing new machinery, revitalizing the factory, or building additions were subject to the machinations of a distant industrial managerial class that did not necessarily prioritize Chicago factories over those elsewhere. Economic control shifted from the local bourgeoisie to a small group of national capitalists with interests across the country.

Secondly, Chicago was subject to the politics of place dependency and property. Industrialists, developers, and other agents with long-term investment in Chicago had focused on making real property attractive to investors since its beginnings in the 1830s. Land was central to successful place-based industrial development in at least two ways: the price, location, and quality of land defined the way that places were articulated to outside interests; and it provided the material basis for local production activity and business interactions. In the case of Royal Metal, Salomon used land in a small Indiana town to siphon off employment from its Chicago works. Through actions such as these, Michigan City was one of many municipalities that contributed to Chicago’s declining place in the metropolitan area from the 1920s. Closer to home, suburbs created more competitive options for industrial land, which over time worked to undermine the city’s economic foundations.

Suburban place makers worked to create advantages that could not be replicated in the city. For heavy industries that required extensive amounts of land, the most obvious was the provision of large tracts of cheap land close to excellent and cheap transportation facilities where complex factory layouts and low-cost working-class housing could be built. Place entrepreneurs also created space that allowed smaller companies experiencing rapid growth and changes to product lines and production processes to substitute rented, generic inner-city spaces for plants specially designed for their new needs. In some cases, suburban place makers put a great deal of forethought into planning the appropriate conditions to attract and retain industry. In others, industrial development was a cumulative process that gathered steam as more and more firms relocated to the suburbs. A brief overview of East Chicago and Cicero illustrates just how industrial suburbs challenged Chicago’s industrial supremacy.

East Chicago was planned as an industrial center from the very start. Initially, its location adjacent to railroads and Lake Michigan, along with large tracts of cheap, level land made the district well suited to industrial pursuits. The first plant opened in 1888, and by 1924, the city had twenty-five thousand workers employed in forty-five firms. The industrial base was anchored by two of the United States’ largest steel corporations: Inland Steel and Youngstown Sheet and Tube. An assortment of associated metalworking and petroleum firms composed the remainder of the city’s industrial base.22 From the 1890s, several land development and infrastructure companies laid out the city for industry. Plans were put in place for the construction of an outer harbor on Lake Michigan, a ship canal from the lake to the Grand Calumet River, and a belt-line railroad to connect the city with other regional railroads. Huge tracts of land close to th...