This is a test

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

"This book accompanies the exhibition "Writing the Garden" organized in 2011 by the New York Society Library."

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Writing the Garden by Elizabeth Barlow Rogers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Filología & Retórica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Teachers in the Garden

PROFESSIONAL landscape designers are more apt to display their work in lavishly illustrated, large-format volumes with beautiful photographs of gardens they have designed than to produce works that fall into the category of garden writing. Their books may be inspirational visual experiences but not especially educational if you are your own garden-maker looking for fundamental design principles, plant knowledge, and practical advice. Only rarely does one find a garden designer’s book that can be classified as both good literature and helpful instruction.

Russell Page

The Education of a Gardener (1962) by Russell Page (1906–1985) is such a book. A memoir in which personal reminiscence, bits of garden history, and numerous original landscape-design suggestions are seamlessly blended, the title reflects its dual nature: a reflection on Page’s own learning process and his desire to impart lessons that will teach by example. The fact that the title is “The Education of a Gardener,” rather than “The Education of a Garden Designer” is subtly important, for even though he did design gardens, the author never veers from being a man for whom the act of gardening is an imperative, with the garden itself being merely the outcome.

In creating gardens for a number of wealthy, famous, and socially prominent clients in the years before World War II, Page developed an idiom that was, above all, responsive to the specifics of place. His first considerations were inevitably topography, climate, existing vegetation, and cultural context. Forced to abandon designing gardens while serving in the Second World War—and, incidentally, at the same time furthering his own education by becoming acquainted with gardens outside the familiar European orbit—he came back to his profession with an understanding of how garden design would henceforth be a matter of working on an altered, smaller scale. Choosing a separate path from that of his modernist contemporaries who had adopted a functionalist ideology, Page based his design philosophy on his own abiding passion for fostering the relationship among plants, nature, architectural forms, and people. Landscape design was for him, first and foremost, an act that occurs in the most literal sense from the ground up. “I have always tried,” he says in The Education of a Gardener, “to shape gardens each as a harmony, linking people to nature, house to landscape, the plant to its soil.” He maintained quite simply that “A good garden cannot be made by somebody who has not developed the capacity to know and to love growing things.”

Well before landscape architects practiced on the global scale that some do today, Page was designing gardens in France, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, and the eastern United States, as well as in his native England. He even had undertaken commissions in Egypt and Persia. Lacking the kind of credentials expected today was hardly a problem, and certainly not one in his eyes. For Page, education was a matter of both seeing and doing. For his purposes it would have been irrelevant and counterproductive to have trained formally in a school of landscape architecture had such an opportunity been available to him.

“ ‘Book learning’ gave me information,” he wrote, “but only physical contact can give any real knowledge and understanding of a live organism.” Not surprisingly, his earliest and most influential book learning came from the public library. There he “found friends and teachers in Reginald Farrer with his English Rock Garden and Gertrude Jekyll with Wall and Water Gardens, two people who had spent a lifetime with plants and gardens.” He was a capable draftsman and always drew plans, but it was only by walking a site many times over that Page, often in consultation with his clients, was able to achieve his vision for a particular garden—a vision that was organic in every sense of the word. Style for him was always a matter of arranging spaces and objects so as to create an integral composition, something that required an understanding of structure, scale, form, color, texture, and ornament as well as knowledge of the physical characteristics and growth habit of plants. He tells his reader, “I think that awareness of the interplay between objects, whether organic or inorganic, is of major importance if your garden is to be also a work of art.” That design ideas were freely borrowed from other cultures did not matter: his gardens were never eclectic pastiches but rather cultural evocations in which his own fundamental design principles and sense of the fittingness of specific foreign influences to place and purpose remained paramount.

Sounding the same note as Wharton and Sitwell, Page speaks of “garden magic.” He too looked for it in Italian villa gardens, reveling in their most magical property, water, and often exploring their furthest recesses to trace the source of a pool, rill, or cascade in a hidden spring or grotto. Devoting a chapter to “Water in the garden,” he recalls the sight of Isfahan where, “on the western edge of the high Asian Plateau water is queen.” Here “a tiny stepped canal runs down the middle of the plane-shaded Charhabagh, perhaps the world’s loveliest processional way, and almost every garden is set symmetrically round a central pool whose four subsidiary rills carry water into each quarter of the garden and then to the roots of every tree and plant.” As is the case with Wharton and Sitwell, the point of such observations is to teach a lesson about the kind of magic that can be applied to one’s own making of a garden. But, with more practical pedagogic specificity than either of them, Page instructs you to observe:

One of the secrets of using running water successfully and naturally in a garden is to avoid forcing it into cascades or fountains which would be at variance with the surrounding landscape. A fountain or jet is apt to look out of place in a garden unless there is a hill somewhere to suggest, at least, that your jet is expressing the force of water coming from still higher ground. For the same reason a fountain or a small pond does not usually look right sheer against a background of sea or lake. In either case it will appear gratuitous or even pretentious.

Only briefly at the age of eighteen, and much later as an adult when he had a small plot behind a London townhouse, did Page have a garden of his own. After a time of avid self-schooling on a corner of his father’s estate in Lincolnshire, his further education was all gained from designing other people’s gardens and looking with a discerning eye at many of the humble and noble, simple and grand gardens of the world. As he says in his introduction, “I never saw a garden from which I did not learn something and seldom met a gardener who did not, in one way or another, help me.” It is fitting, therefore, that in the final chapter of The Education of a Gardener, titled “My Garden,” Page allows himself to fantasize about what kind of garden he would in fact make for himself, were he able to choose any site he wished.

Not surprisingly, it would be a garden in England. Since it would be his personal garden, he would have “a workroom with one wall all window, and below it a wide work table running its whole length with a place to draw and a place to write.” This room would have whitewashed walls, a brick floor, and an entire wall for books. Outside the window Page imagines an experimental garden of square beds, each of which “will be autonomous, its own small world in which plants will grow to teach me more about their aesthetic possibilities and their cultural likes and dislikes.” This will be, he says, “my art gallery of natural forms, a trial ground from which I will always learn, [the place where] I shall find, living and growing, the coloured expansions of my pleasures as a painter and gardener, as well as an addict of catalogues and dictionaries.” Leaving this practical corner, he then takes us on a walk through all the passages of this garden of fancy in the same way that Gertrude Jekyll might conduct us around Munstead Wood, a tour in which the lessons of the preceding pages of his book coalesce into a verbal picture. Then at the end Page gives himself up to dreaming of entirely different landscapes and sets of conditions under which to construct other imaginary garden castles in the air. Here lies the final lesson of this remarkable book: like real gardens, dream gardens are worlds unto themselves, “dimensioned in time as well as space; where each leaf, though long since dead and withered, burgeons again and the gossamer web for ever catches the dew of a morning long since past.”

Penelope Hobhouse

Penelope Hobhouse’s (b. 1929) career as a garden designer began with the restoration of the gardens at Hadspen, her former husband’s ancestral home in Somerset. In the introduction to her first book, The Country Gardener (1976), she acknowledges the extent to which Margery Fish, who lived nearby, gave her moral support and many stimulating ideas. Like Fish’s books, which were her personal garden primers on herbaceous plants, Hobhouse’s have since tutored a new generation of garden-makers. Along with the late Rosemary Verey, she has carried forth the long Arts and Crafts garden tradition begun by Gertrude Jekyll—a garden style that glories in the interplay between the architecture of green hedges, mellow stone walls, old brickwork, and the painterly effects achieved by an experienced and imaginative eye for plant color and form. In its relaxed sophistication—a rendition of the cottage garden writ large—it is a quintessentially English style, one that is aided by the advantages of climate and long tradition. Contemporary gardeners who practice and perpetuate it are indebted to Sissinghurst and Hidcote, the two twentieth-century gardens that famously pioneered the paradigm of the garden as a series of hedge-enclosed “rooms.” Like their creators, Hobhouse is first and foremost a plant person who uses an in-depth knowledge of the forms, textures, and colors related to seasonal blooming times to make a garden interesting year-round.

Acknowledging the effects on the English garden of waning national economic prosperity, the austerity imposed by two world wars, exponentially higher taxes, and a shortage of labor, Hobhouse’s no-nonsense advice is this:

Achievement of beauty alone is not worth the overstraining of physical strength or financial resources and we should cut our cloth according to our means. Limited labour and limited income now make it necessary for us to practice less costly ways of gardening than those of some of our predecessors, even if we have the same area to maintain. Most of our planting schemes, after an initial period for establishment, should be designed to save maintenance costs and effort. Within that context we can please ourselves as to our specialist enthusiasms.

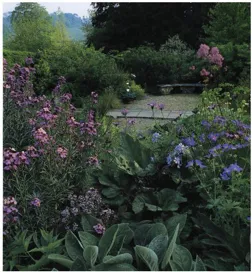

The Garden at Hadspen

From the Peach Walk at Hadspen, the view reaches out into the countryside beyond the garden. Planting in the foreground is framed by older trees and shrubs growing at a lower level. In the border are mauve-flowered Erysimum linifolium, Phlox ‘Chattahoochee,’ and Geranium sylvaticum ‘Mayflower,’ together with silver-leaved stachys. Photograph by Steven Wooster. Courtesy of Little, Brown and Company.

Before looking at how Hobhouse’s seven-acre garden at Hadspen and her familiarity with other English gardens have enhanced her design skills and knowledge of the growing habits of plants, it is worth pausing a moment to glance backward. Reginald Arkell’s fine novel Old Herbaceous (1951), set in the twilight of the era when head gardeners presided over large estates, provides a benchmark for assessing the descending fortunes of the great nineteenth-century English gardens. Instructive too in this regard are PBS Masterpiece television productions and Merchant and Ivory movies that portray English gardens in their Edwardian glory days. Swept away by World War I were Picturesque pleasure grounds; rolling fields bounded by wooded brakes from which dogs flushed foxes for hunters; ornamental planting beds with changing seasonal displays of annuals in bloom; conservatories for exotic ferns and palms; hothouses for out-of-season-fruits, vegetables, and tropical flora; cutting gardens for flowers to decorate the rooms of great houses; and kitchen gardens to furnish food for house parties of twenty or more guests. These upper-class landscape and horticultural luxuries were superseded at first by the Arts and Crafts and Italianate gardens of the early years of the twentieth century, which introduced gardening on a somewhat reduced but nevertheless impressive scale. With head gardeners a vanishing breed, there was more owner involvement in the planning and maintaining of gardens. The years leading up to and following World War II saw further curtailment of maintenance staff. This and the vanishing of large family fortunes sparked the creative reinvention of the English garden within even more constricted boundaries, notable examples from this era being Margery Fish’s East Lambrook and Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson’s Sissinghurst. After the wartime hiatus and under economic constraints that enforced a high degree of practicality, the English genius for gardening as an art form continued to reassert itself, but now even more ingenuity was necessary to produce the renaissance that continues to the present day.

Thus Hobhouse’s mission in The Country Gardener is to teach other gardeners the cloth-cutting principles of small-scale gardening. Sensible considerations of...

Table of contents

- eBook Cover

- Title Page

- Front Matter

- Preface

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Women in the Garden

- Warriors in the Garden

- Rhapsodists in the Garden

- Nurserymen in the Garden

- Foragers in the Garden

- Travelers in the Garden

- Humorists in the Garden

- Spouses in the Garden

- Correspondents in the Garden

- Conversationalists in the Garden

- Teachers in the Garden

- Philosophers in the Garden

- Conclusion

- Afterword

- Selected Bibliography