eBook - ePub

The Parallel Curriculum in the Classroom, Book 1

Essays for Application Across the Content Areas, K-12

This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Parallel Curriculum in the Classroom, Book 1

Essays for Application Across the Content Areas, K-12

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Further developing key ideas from the highly acclaimed original book, these essays include guidelines for designing curriculum units based on the Parallel Curriculum Model.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Parallel Curriculum in the Classroom, Book 1 by Carol Ann Tomlinson, Sandra N. Kaplan, Jeanne H. Purcell, Jann H. Leppien, Deborah E. Burns, Cindy A. Strickland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Curricula. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

In Praise of Protocols

Navigating the Design Process Within the Parallel Curriculum Model

One day last autumn, I spent about eight hours in the library of a public high school meeting with two groups of teachers and administrators who wanted to talk about curriculum, what made it exemplary, and how to design it to support thought-provoking learning for their students. By midday, I found myself with a little spare time as I waited for a second group to arrive. To stretch my legs, I roamed the rows and shelves of the library and soon spotted a book that piqued my curiosity. It was a reference book that explained the historical origins of many contemporary words and phrases. For my own amusement, I decided to find out if the book contained the word curriculum. Sure enough, the word has had a very rich history. With the initiation of the Parallel Curriculum Model (PCM), the word will surely have an even more interesting future.

CURRICULUM AS A ROAD MAP

The earliest meaning of the word curriculum, “a messenger’s running course,” can be traced to ancient Roman times. Later, in the 17th century, the word’s meaning was transformed by the Scots to describe a different kind of course, “a carriage way or roadway.” By 1904, the word curriculum appears to have changed its meaning once again, this time by users in the United States, to indicate “a student’s course of study.” Then, in the 1940s, the word’s meaning evolved again, to connote “a plan of study for a given subject area or grade level.” This explanation continues as our contemporary definition of the term.

It is interesting to consider how the historical meaning of the word curriculum continues to influence our contemporary perceptions and usage. As a metaphor, the notion of curriculum as a roadway for a learning journey provokes intriguing questions. Who are the travelers? What is their destination? Can different travelers have different destinations? Who prepares the map for the journey, and how do they create it? Who uses the map, and what do the travelers need to realize a successful journey?

This metaphor also helps us define our roles as curriculum writers and teachers. Depending on which role we assume, we might act as curriculum cartographers who create the road map and plan for student learning. Or, as teachers, we might serve as travel guides who use a curriculum road map to lead students along their learning journey. Both roles demand that we understand our learners, the learning process, and the kind of knowledge we want students to acquire as a result of their learning journey.

THE PURPOSE, PROBLEMS, AND PROCESS OF CURRICULUM WRITING

Most of us acknowledge that a curriculum plan is important. It confirms and communicates our learning objectives, ensures the proper integration and configuration of the various curriculum components, and ensures the alignment of content across grade levels, classrooms, and related topics in the same subject area.

However, there is a big difference between using a curriculum map created by someone else and being the cartographer who maps the way for others. Curriculum writing, like the mapping and planning process, is hard work. It requires time, patience, collaboration, research, dialogue, experimentation, reflection, revision, and a willingness to resist premature closure.

The mission of creating units based on the PCM, units that focus on discipline-based content; topic, time, or cultural connections; authentic practices and applications; or personal identity, is tantalizing and promises to make the hard work worthwhile. PCM also promises the opportunity to provide side trips during the learning journey to address differences in students’ levels of expertise as well as their personal strengths and interests. But how do we go about drawing a better plan and map, based on the PCM, that supports the learner’s journey to new and more challenging destinations?

THE GOAL AND SEQUENCE OF THIS ESSAY

This essay shares a process and protocol for writing PCM curriculum that evolved during the course of a yearlong project. The effort involved more than 40 different classroom teachers, gifted education specialists, administrators, university professors, and state department of education consultants from around the country. Working individually, in pairs, and in small groups, these educators were charged with the development of 24 different PCM curriculum units in science and social studies for students from varying socioeconomic and achievement levels.

Our long-term collaboration provided an ideal opportunity to observe, reflect upon, and describe the PCM design process. In addition, this partnership helped us articulate a common vision for PCM curricula, clarify the guiding questions we posed to ourselves during the process, identify the sequence of steps that appear to be most effective, and develop graphic organizers and templates to support the design process and communicate effectively with each other during that process. This essay shares these templates, procedures, and processes with others in an attempt to make the PCM curriculum writing process easier to organize and accomplish.

I begin the description of the design process with a discussion of the key components that are part of a curriculum plan. I also emphasize the reasons why educators need to articulate the first component—content and learning goals—from the start. Next, I consider the importance of modifying, aligning, and combining all the components to suit the unique purposes of each of the parallels in the PCM. Third, I investigate the definition of a protocol and a template and examine their purpose, usefulness, and constraints.

In the last two-thirds of this essay, readers will encounter a detailed explanation of the ten steps (or protocol) that most of our author cadre appeared to use in creating the PCM curriculum units. This protocol begins with three steps that helped our cadre of authors identify, categorize, and sequence the content goals for a PCM unit. The fourth step in the process involves the identification of the major segues within the unit and the time parameters for each section. Fifth, authors identify the appropriate teaching and learning activities, resources, and student products. Sixth, authors share focusing questions and the graphic organizers that helped them develop a learner profile and create appropriate opportunities for Ascending Intellectual Demand (AID). The seventh step provides an opportunity to explore the relationships among student products, rubrics, AID, and assessment. The eighth step reconsiders choice of content, tasks, time allocations, and related parallels in order to ensure alignment and make appropriate modifications. In the ninth step, readers review a graphic organizer useful in making decisions about what to include in an effective introduction to the unit. At the conclusion of these steps, or decision-making points, our cadre was ready to begin the tenth step, writing the actual lesson plans for their respective PCM units. The last section of this essay contains the templates and graphic organizers they used to develop the plans.

The set of steps for the PCM design process described in this essay was common to most of the authors in our project. To date, the strategies and protocols they used have been successful in supporting the work of other PCM authors, even though some authors skip steps or use the steps in a different order. The protocol I describe in this essay is by no means the only way to organize the common work of a group of authors or to design PCM curricula. It is likely that other groups, working within a different organizational structure or school culture, have developed or will continue to develop alternate methods that are just as effective or more comprehensive. We invite their collaboration and willingness to share their work. Their creativity and alternate perspectives deepen our understandings about PCM, its numerous facets, and its unexplored avenues and possibilities.

COMPONENTS OF A CURRICULUM PLAN

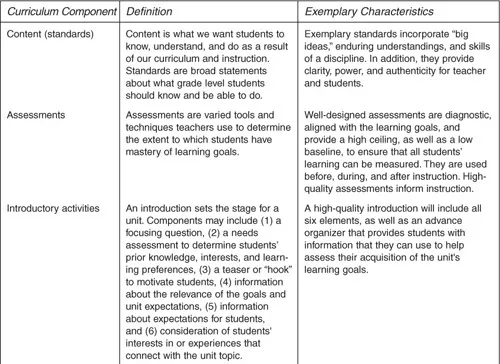

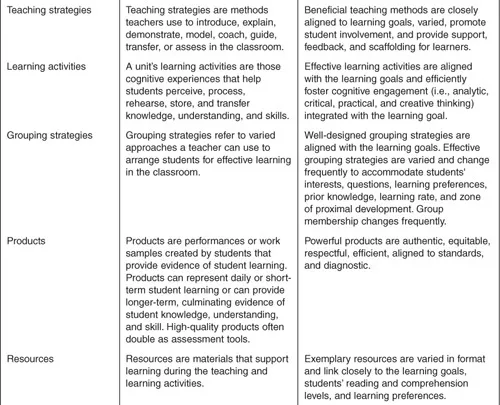

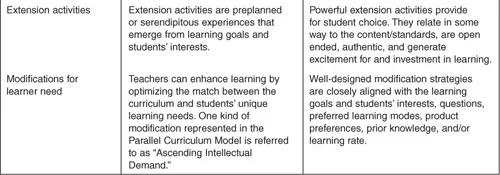

All curriculum units, those based on the PCM or any other model, can include a number of key features that support student learning. To be useful, even a basic curriculum guide must include content standards that students are to acquire and the topics or examples they will use to learn the content, time allocations needed to accomplish the learning, and assessment systems to track student progress and learning from the beginning to the end of the curriculum unit. In writing the Parallel Curriculum, we determined that a more comprehensive curriculum guide should include the components listed in Figure 1.1.

We quickly discovered that one of the possible components, the content we want students to learn and be able to apply, was the most important component for our decision making and planning. Comparable to the learner’s or traveler’s destination on a curriculum map, the nature of that content (e.g., facts, concepts, generalizations, principles, skills, attitudes, or applications) and the relative importance of each kind of knowledge addressed in the unit determine the use of one or more of the PCM parallels and, as a result, the unique configuration of the other elements that support the acquisition of this content knowledge. We explore the alternatives for selecting content in the first three steps of the writing protocol that follows.

THE CHALLENGE OF WRITING WELL-ALIGNED PARALLEL CURRICULUM MODEL CURRICULA

But designing PCM units, or any other kind of curriculum, is more than naming the content students are to learn. The following metaphor illustrates this basic understanding.

Like a list of food items needed to create a particular dish, the curriculum components act as the raw ingredients necessary to prepare and “serve” a particular lesson within a curriculum unit. There is, however, all the difference in the world between a pile of groceries sitting on a kitchen counter and a flavorful and nutritious dish served hot from the oven. To obtain the latter, the skillful cook must carefully choose the freshest and most appropriate ingredients, blend them together in just the right proportions, and apply heat energy to transform the uncooked ingredients into a satisfying, nourishing meal.

Likewise, the curriculum developer must carefully choose the ingredients of the lesson, combine them just so, and then apply the energy needed to transform the lessons into truly powerful learning experiences. Certainly, appealing to students’ imagination and recognizing and attending to their prior knowledge by making the learning journey and content relevant to their individual lives is one way to capture this energy. Other methods involve the use of constructivist teaching and learning methods, the use of authentic resources and assignments, and the guarantee of appropriate levels of challenge for all students. All of these expectations are inherent in the design process for any of the PCM parallels (see the The Parallel Curriculum for an in-depth discussion).

Figure 1.1 The Components of Comprehensive Curriculum

SOURCE: Copyright © 2002 by National Association for Gifted Children. All rights reserved. Reprinted from The Parallel Curriculum by Tomlinson et al. Published by Corwin Press, Inc. Reproduction authorized only for the local school site that has purchased this book.

Other issues that arise in developing solid curricula are the sequencing of the content and the allocation of time for learning each major piece of knowledge within a given curriculum unit. The most difficult part of creating a curriculum unit isn’t making one “dish,” or writing one lesson; it’s how we go about making sure that all of the dishes on the menu are sequenced appropriately as first, second, and third courses throughout the duration of the meal (or curriculum unit).

A curriculum plan—especially one based on PCM—is more than raw ingredients or a disjointed set of entrees, and it has as much to d...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Introducing the Parallel Curriculum Model in the Classroom

- 1. In Praise of Protocols: Navigating the Design Process Within the Parallel Curriculum Model

- 2. The Importance of the Focusing Questions in Each of the Curriculum Parallels

- 3. Using the Four Parallel Curricula as a Comprehensive Curriculum Model: Philosophy and Pragmatism

- 4. Exploring the Curriculum of Identity

- 5. Ascending Intellectual Demand Within and Beyond the Parallel Curriculum Model

- Bibliography

- Index