eBook - ePub

Reaching and Teaching Middle School Learners

Asking Students to Show Us What Works

This is a test

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reaching and Teaching Middle School Learners

Asking Students to Show Us What Works

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Enhance classroom practice by inviting students to offer feedback on pedagogy, learning styles, and their needs and preferences.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Reaching and Teaching Middle School Learners by Penny A. Bishop, Susanna W. Pflaum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Teaching Methods. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Case for Consulting Students

Decades of calls for reform have not succeeded in making schools places where all young people want to and are able to learn. It is time to invite students to join the conversations about how we might accomplish that. (Cook-Sather, 2002, p. 9)

What happens when we do invite students to join conversations about school and school reform? What are their perspectives, and how might we use those perspectives to shape our practices as educators? This is a book about students’ perceptions of academic engagement. In it, we present two central ideas. First, we consider what the fifty-eight middle schoolers in our study identified as central to their learning. Through their words and drawings, we come to see common themes across the group and consider the implications of these needs on classroom practice. Second, and perhaps more important, we urge you as educators to invite your own students into the conversation about schooling, to uncover your own students’ perspectives on what engages them in learning. We do not propose that what our middle schoolers convey is what all students experience; rather, this book models an approach to action research that can help you learn from your students and shape life in your classroom based on that new knowledge.

LEARNERS: THE MISSING VOICE IN SCHOOL REFORM

School reform is a centuries-old endeavor. Veteran teachers can attest to the myriad initiatives that spiral through public education in the name of improvement and accountability. Yet, the vast majority of reform efforts rely on adult perspective, on what administrators, legislators, school boards, parents, teachers, and other adult stakeholders identify as central to improving student learning. Rarely are students consulted in attempts at school renewal. In fact, Erickson and Shultz’s (1992) speculation on the role of student experience in school improvement more than a decade ago remains relatively true today:

Virtually no research has been done that places student experience at the center of attention. We do not see student interests and their known and unknown fears. We do not see the mutual influence of students and teachers or see what the student or the teacher thinks or cares about during the course of that mutual influence. If the student is visible at all in a research study he is usually viewed from the perspective of adult educators’ interests and ways of seeing. (p. 467)

Soo Hoo (1993) also highlighted the need for student voices in research that inform school change: “Traditionally, students have been overlooked as valuable resources in the restructuring of schools. Few reform efforts have actively sought student participation to inform restructuring efforts” (p. 392). In their discussion of schooling for young adolescents, Dickinson and Erb (1997) underscored this assertion: “Very few of the studies we found were written from teachers’ perspectives. None were written from students’ points of view. We need more studies written with the voices of teachers and students” (pp. 380–381). And Cook-Sather (2002) openly chided, “There is something fundamentally amiss about building and rebuilding an entire system without consulting at any point those it is ostensibly designed to serve” (p. 3).

We agree. Eliciting students’ perspectives on current school initiatives, on instructional practice, and on matters of curriculum can be a powerful and effective means of meeting students’ educational needs. Consulting directly the most important stakeholders—the students themselves—is critical to their academic engagement.

ON STUDENT ENGAGEMENT

As we build, and rebuild, the educational system, student achievement remains largely at the center. We know that for students to achieve, they must be engaged (Finn, Pannozzo, & Achilles, 2003). Many factors can increase student engagement, including type of instructional materials (Lee & Anderson, 1993); the subject matter and the authenticity of instructional work (Marks, 2000); and real-world observation, conceptual themes, and self-directed learning (Guthrie & Wigfield, 1997).

But how do we know that students are engaged? Most often, students’ academic engagement is measured by adults’ observation of students’ time on task. Observers determine when and to what extent students are engaged in the learning at hand. Can observers always adequately determine engagement? Surely when writing, planning, or acquiring a new idea, hobby, or skill, we do not always outwardly appear to be attending, even while we are truly “engaged.” How often do we appear to be attentive, engrossed in a lecture, a sermon, or even a monologue on the other side of the telephone when in truth we are “miles” away? Young students learn very early to “pretend-attend.” They learn to hide their confusion, their sense of failure, their secret off-task fiddling or drawing, their secret communications to friends, all the while giving every indication of attention. Given widespread pretend-attend, how often do we misread a student’s level of engagement? And, if we misread engagement, how well can we respond to students’ needs? Our method of discovery was to ask students. In the process we learned a lot, not the least of which was that when it is safe to do so, middle grade youngsters really like to talk about their experiences of school.

OUR STUDY AND METHODS

There is a fundamental premise to this book. If we really want to know what engages students, we need to ask them. Schubert and Ayers (1992) wrote, “The secret of teaching is to be found in the local details and the everyday life of teachers…. Those who hope to understand teaching must turn at some point to teachers themselves” (p. v). What if one replaced the words teaching and teachers with learning and learners? Just as it is important to turn to teachers to understand teaching, we must turn to students to understand learning. Asking students about times when they were actively learning and engaged moves beyond the constraints of observable time on task to uncover the complexities and messiness of true learning.

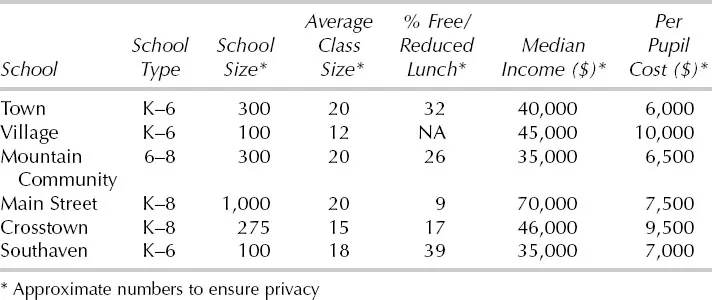

Learners have much to say about the quality of their schooling experiences. They provide rich insight into what “works” for them and, perhaps even more clearly, what does not. In an attempt to capture these perspectives, we consulted fifty-eight young adolescents in Grades 4 through 8 from six schools, which are described in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 School and Community Attributes

Stage 1

To understand students’ perceptions of engagement, we began by individually interviewing twenty of the students from four of the schools. (Students, teachers, parents, and principals all provided written consent.) We invited students to draw and to talk about their educational experiences. To do this, we used four basic prompts, the exact wording of which varied based on the developmental level of the student:

1. Please describe a typical school day.

2. Please draw a time in school when you were really engaged, focused, and learning a lot, and then describe it.

3. Please draw a time in school when you were not engaged, not focused, and unsuccessful, and then describe it.

4. If you had a magic wand and could change anything about school, what would you change and why?

We asked students to draw in Prompts 2 and 3 because we were mindful of the challenges of reflecting retrospectively on learning tasks. Erickson and Schultz (1992) warned,

Interviewing after the fact of immediate experience produces retrospective accounts that tend not only to be over rationalized but that, because of the synoptic form, condense the story of engagement in a way that fails to convey the on-line character of the actual engagement. (p. 468)

Drawing provides a powerful window into the minds of children. As a supplement to the interview, drawing placed the students back in the moment, and the feelings surrounding the events emerged. In talking about the pictures, the students elaborated and extended their experiences, and had the opportunity to convey their ideas without relying solely on verbal means. Although educational researchers rarely use drawing to capture what students think about their education (Haney, Russell, & Jackson, 1998; Olson, 1995), drawing can be a powerful lens into learners’ perceptions (Haney, Russell, & Bebell, 2004).

We followed these twenty students through to their next school year, visiting them again for a shorter interview. During this second interview, we inquired about various themes that had emerged from the earlier data, including reading and the role of debate and disagreement in students’ classrooms. We also had a chance to “member-check,” or to ask the students if our interpretations of the previous year’s comments and drawings were valid.

Stage 2

Realizing that the power of this approach lay in connecting teachers with their own students’ needs, we engaged another thirty-eight...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- 1. The Case for Consulting Students

- 2. The Social Lives of Schools and Classrooms

- 3. Choice, Action, and Relevance in Curriculum

- 4. Math Is the Measure

- 5. Reading in School

- 6. Inquiring and Communicating in Science and Social Studies

- 7. Consulting Your Students

- References

- Index