![]()

PART ONE

Formalism, Enthusiasm, and True Religion, 1740–1820

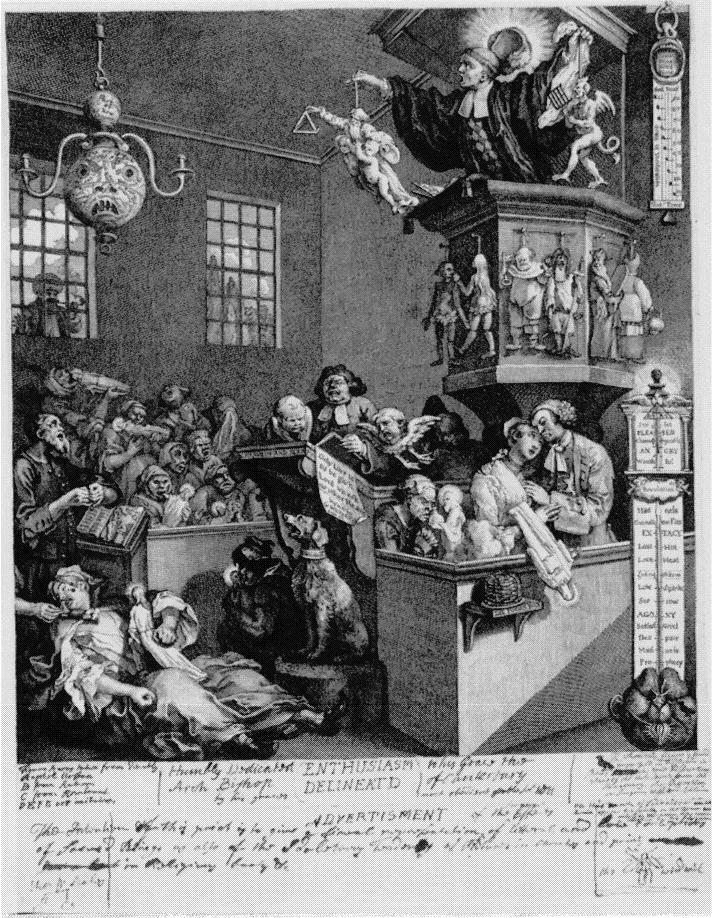

1. William Hogarth, “Enthusiasm Delineat’d” (c. 1760). Courtesy of the British Museum. A satirical depiction of Methodist “enthusiasm.” The puppets suggest the literal manner in which the preacher (modeled on George Whitefield) employed metaphors. The two thermometers register the loudness of the preacher and the reaction of the congregation. The latter ranges from the “Luke Warm” midpoint to the extremes of “Madness,” “Prophesy,” and “Revelation” at top and bottom. The congregational thermometer rests on the “Methodist brain.” The woman at the left has reached the “Convulsion Fits” stage and is being offered smelling salts (Ronald Paulson, Hogarth’s Graphic Works, 3rd ed. [London: The Print Room, 1989], 175–77).

TWO CAMISARD prophets arrived in London in 1706 and created an immediate stir with their inspired prophecies of the imminent Second Coming of the Lord. The Camisards, or French Prophets as they came to be known in England, were a radicalized remnant of the French Calvinist Pluguenots. With the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, Protestantism was outlawed in France, public worship was forbidden, schools were closed, pastors exiled, and the people forced either to convert to Catholicism or emigrate. Those who stayed maintained traditional forms of private and family devotion in secret. In this context, the Huguenot remnant turned to the prophetic books of the Bible and to direct inspiration. Inspired lay persons (inspiré), often young women, sometimes fell into “Natural Lethargy, . . . without any appearance of a violent motion”; other times they were wracked by convulsions. Most often they fell or fainted or swooned (évanouir). They would then “Prophesie and Preach in their Sleep,” typically without remembering what they said once they “awoke.”1 An English critic provided the following description of the French Prophets soon after they arrived in London:

. . . their Countenance changes, and is no longer Natural; their Eyes roll after a ghastly manner in their Heads, or they stand altogether fixed; all the Members of their Body seem displaced, their Hearts beat with extraordinary Efforts and Agitations; they become Swelled and Bloated, and look bigger than ordinary; they Beat themselves with their Hands with a vast Force, like the miserable Creature in the Gospel, cutting himself with Stones; the Tone of their Voice is stronger than what it could be Naturally; their Words are sometimes broken and interrupted; they speak without knowing what they speak, and without remembering what they have Prophesied.2

Promptly repudiated by the more moderate Hugenots who had emigrated earlier, the French Prophets epitomized “enthusiasm” for many early-eighteenth-century Anglo-Americans.

The specter of the French Prophets haunted the transatlantic awakening of the 1730s and 1740s. Opponents of the revivals in Great Britain and the American colonies compared the bodily agitations of the French Prophets with those of Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and Methodists. In Scotland, opponents of the revivals circulated the writings of the French Prophets to make the comparison obvious. In 1742, “anti-enthusiasticus,” probably the American Congregationalist minister Charles Chauncy, published a tract subtitled A Faithful Account of the French Prophets, their Agitations, Extasies, and Inspirations in both Glasgow and Boston. An appendix explicitly compared the French Prophets to the “Enthusiasts” of New England. George Lavington, an Anglican bishop, brought out what he took to be the unfortunate similarities between Methodists, the French Prophets, and Roman Catholics in The Enthusiasm of Methodists and Papists Compared (1749). Leading spokesmen for the transatlantic awakening emphatically rejected the charge of enthusiasm. They did so, not by defending the French Prophets, but by repudiating them. Whatever their differences, those who weighed in for and against the revival agreed that the French Prophets were “enthusiasts” and that “enthusiasm” was bad. Only John Wesley, of all the prominent Methodist and Reformed leaders, evidenced any ambivalence in this regard.3

While Wesley emphatically opposed enthusiasm, he was himself more regularly painted with the brush of enthusiasm than most of the moderate revival leaders and more open than they to finding something of true religion in those usually designated as enthusiasts. In January 1739, having “long been importuned” to do so, Wesley went with several friends from the Fetter Lane society to visit the French Prophet Mary Plewit. Wesley reports that “two or three of our company were much affected [by her prophesying] and believed that she spoke by the Spirit of God.” As for himself, he said, “this was in no wise clear to me.”4 While John Wesley did not actually conclude that Plewit was speaking by the Spirit of God, he at least seemed open to the possibility.5 When an anonymous Anglican critic argued that Wesley’s claims regarding the “perceptible inspiration” of the Holy Spirit were “never maintained but by Montanists, Quakers, and Methodists,” Wesley did not respond defensively, already having indicated to Smith that “if the Quakers hold the same perceptible inspiration with me I am glad.”6

In 1750, twelve years after his initial contacts with the French Prophets, Wesley read one of their books, John Lacy’s The General Delusions of Christians of with Regard to Prophesy (1713). Although critics had circulated the book widely in order to discredit the revival, Wesley was convinced by Lacy, “of what [he] had long suspected,” that the Montanists, to whom both the French Prophets and the Methodists had so often been compared, “were real, scriptural Christians.” Moreover, he concluded, “the grand reason why the miraculous gifts were so soon withdrawn, was not only that faith and holiness were well nigh lost; but that dry, formal, orthodox men began even then to ridicule whatever gifts they had not themselves, and to decry them all as either madness or imposture.”7

The shifting patterns of accusation and counter-accusation reveal the contested space in which religious experience was constituted. As these vignettes are meant to suggest, the language of religious experience developed, not in isolation, but hand-in-hand with the language of enthusiasm and formalism. Both enthusiasm and formalism were epithets used to disparage what their beholders viewed as false forms of Christianity. Neither concept was new in 1740 or even 1640, but they derived much of their eighteenth-century meaning from the events of a hundred or so years earlier, specifically the rise of Puritanism within the Church of England and the outbreak of the English Civil War. Thus, from the mid-seventeenth century at least, a “formalist” was understood as one who had the form of religion without the power, while an “enthusiast” was understood as one who falsely claimed to be inspired.8 Both terms came to the fore with the Puritan emphasis on “inward” or “heart” religion. Puritans used the word “experience” to talk about this dimension of inwardness. One mid-seventeenth-century Puritan autobiographer referred to “experience” as “the inward sense and feeling of what is outwardly read and heard; and the spirituall and powerfull enjoyment of What is believed.” Another described it as “truth brought home to the heart with life and power.” As these definitions’ references to “power” suggest, Puritans disparaged the absence of experience as “formalism.” Conversely, non-Puritans disparaged the “inward sense and feeling,” that is the “experience,” of the Puritans as “enthusiasm.”9

While both “enthusiasm” and “formalism” were epithets, enthusiasm was by far the more potentially damaging of the two insults. The emotional freight attached to the term went back to what were for many the dual traumas of the mid-seventeenth century—regicide and republicanism. It is hard to appreciate the passions aroused by the specter of enthusiasm through the eighteenth and into the nineteenth century unless we understand the word as one associated with wounds deep in the Anglo-American psyche. Modern historians have been at times too quick to recapitulate a theological reading of the history of enthusiasm, tracing it back, following seventeenth- and eighteenth-century thinkers, to the Anabaptists or the Montanists. In so doing they have essentialized and decontextualized our understanding of anti-enthusiastic rhetoric, ensnared us in fruitless attempts to separate real enthusiasts from those falsely accused, and made it difficult to understand how persons could be both opposed to and accused of enthusiasm.10

As late as the 1640s, the term “enthusiasm”—derived from the Greek en theos, meaning to be filled with or inspired by a deity—was simply an attribute, albeit a negative one, often associated with Puritans. With the publication of The Anatomy of Melancholy in the 1620s, Robert Burton introduced long-standing medical discussions of the religious symptoms of melancholics into the realm of religious polemics. “Enthusiasts” appeared in lists of persons prone to religious melancholy, as in “Hereticks old and new, Schismaticks, Schoolmen, Prophets, Enthusiasts, & c.”11 Many in England came to identify “Religious Melancholy,” which Burton constituted as a “distinct species” of the more traditional medical malady “Love-Melancholy,” with Puritanism.12 Opponents of Puritanism began to associate “Enthusiasms and Revelations,” both synonyms for inspiration, “with mental and emotional derangement.”13

During the 1640s, with religious toleration and the lifting of censorship, religious literature, including radical religious pamphlet literature, burgeoned.14 Many of these radical publications were spiritual autobiographies; among them were the first religious titles containing the word “experience.”15 Although numerous publications appeared at this time condemning sects, sectaries, schismatics, errours, heresies, and blasphemies, their titles did not refer to enthusiasts or enthusiasm.16 It was during the 1650s, with the publication of Meric Causaubon’s Treatise Concerning Enthusiasme (1655) and Henry More’s Enthusiasmus Triumphatus (1656), that enthusiasm took on new prominence as a negative catchall term for what had been formerly conveyed by schismatic, sectarian, and heretic.17

In contrast to sectarian and schismatic, which were linked to false ecclesiology, and heresy, which was linked to false doctrine, enthusiasm defined illegitimacy in relation to false inspiration or, more broadly, false experience. Enthusiasm, unlike schism or heresy, located that which was threatening not in challenges to ecclesiology or doctrine but in challenges to that most fundamental of Christian categories—revelation.18 As such it lifted up the Puritan claim to access God in relatively direct fashion through a combination of spirit, word, and ordinance (baptism and the Lord’s supper). The precise mix of factors was a matter of considerable controversy among Puritans with opinion ranging from the relatively traditional emphasis of Presbyterians on the inspiration of the spirit in a context of fixed liturgies and clerically interpreted scriptures to the radical Quaker principle of the “Spirit in every man.” It was this Puritan desire to access God directly that, as Peter Lake points out, linked moderate and radical Puritanism before and after 1640 and was, in his words, “arguably . . . a central strand in the events that produced the regicide [the beheading of Charles I] and the republic, the protectorate and, indeed, the restoration [of the monarchy].”19

While, generally speaking, “enthusiasm” challenged Puritan claims to access God directly, anti-enthusiasts saved their greatest fury for those who emphasized the revelatory power of dreams, visions, and audible voices, an emphasis particularly marked in the new literature of “spiritual experience” published by the more radical Puritans.20 The same desire to access God directly was apparent almost a century later in Jonathan Edwards’ claim that the “Spirit of God” dwells in all true saints and in John Wesley’s expectation that every true Christian would receive “the witness of God’s Spirit with his spirit, that he is a child of God.” It was these claims, so central to the theology of each, that opened Edwards and Wesley to charges of “enthusiasm.” As in the mid-seventeenth century, the claims to see the action of God in dreams, visions, and involuntary bodily movements on the part of eighteenth-century evangelicals invited the most hostile attacks.

Enthusiasm, unlike formalism, was more than just an epithet used by critics to denigrate the claims of their opponents. It was additionally, and more precisely, a theoretically laden epithet that had the effect of recasting the theological claims of one’s opponents as “delusions” that could be explained in secular, scientific terms. Causaubon and More, both Anglicans and royalist in their sympathies, wrote their influential works on enthusiasm in the second decade of republican rule and were part of the growing backlash against the democratic vision of radical Puritans that led to the protectorate and the restoration.21 In elevating the concept of enthusiasm as a catchall term for religious dissent, “Enlightened” Anglicans drew upon Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, which, following medical and philosophical tradition, associated enthusiasm with madness or pathological religious despair. In doing so, they recast the problem of religious dissent in terms of mental illness rather than heresy. By associating that which was problematic—indeed that which had produced regicide and republic—with false inspiration rather than false doctrine, enthusiasm could be explained in scientific rather than theological terms. Recast as delusion or madness, political and religious radicalism was more easily contained.

The anti-enthusiasts’ case against democratic radicalism was further strengthened by the creation of a comparative history of enthusiasm that overlapped with and, in Anglo-American Protestant circles, often superseded the history of heresy. Causaubon describes his twofold purpose as first, “by examples of all professions in all ages, to show how men have been very prone upon some grounds of nature ... to deem themselves divinely inspired” and, second, to discover “reasons, and probable confirmations of such natural operations, falsely deemed supernatural.”22 The quest for explanations of “divine inspiration” upon “grounds of nature,” that is, for “reasons” that would account for “natural operations, falsely deemed supernatural” was central to the development of Enlightenment thought. With the Restoration of the monarchy, the enlightened fear of enthusiasm was coupled with a desire for an end to religious disputes. As one contemporary put it, “since the King’s return, the blindness of the former Ages and the miseries of this last, are vanish’d away: now men are generally . . . satiated with Religious Disputes: . . . Now there is an universal desire, and appetite after knowledge, after the peaceable, the fruitful, the nourishing Knowledge: and not after that of antient Sects, which only yielded hard indigestible arguments.”23 In this quest for an end to religious dispute, enthusiasm (along with superstition) held pride of place as the enemy of reason.

All the moderate leaders of the early-eighteenth-century revival, therefore, took aggressive action to distance themselves from the threat of enthusiasm. Most of the moderates, including George Whitefield and Charles Wesley, actively discouraged bodily manifestations while they were preaching. Others, such as Jonathan Edwards in New England and James Robe in Scotland, not only discouraged these bodily manifestations, they joined with ministerial crit...