![]()

Michael Pennington

on

Timon

Timon of Athens (1605–7)

Royal Shakespeare Company

Opened at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon on 24 August 1999

Directed by Gregory Doran

Designed by Stephen Brimson Lewis With Sam Dastor as Poet, Richard McCabe as Apemantus, Rupert Penry-Jones as Alcibiades, and John Woodvine as Flavius

Timon of Athens is the story of a man who goes from having everything to having nothing. It is a play of two very different halves. At first, Timon has, or thinks he has, vast wealth. He lavishes extravagant gifts on a circle of flattering, apparent friends. As a result of his profligacy he becomes bankrupt. When he asks his ‘friends’ for help, they desert him.

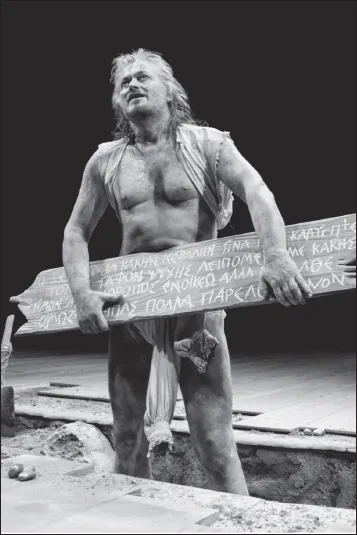

Timon leaves Athens, enraged, heaping curses on humankind. He goes to live in a cave in the woods, dressed in rags, seeking solitude. He digs, in search of a root to eat. Instead he finds a huge stash of gold – which is useless to him because he can’t eat it. The irony is compounded as news of his renewed wealth spreads and Timon is once again invaded by grasping visitors. He dies on a lonely beach.

Timon of Athens is one of Shakespeare’s later plays, probably not all his own work, but with passages written by Thomas Middleton. It appears to be an unfinished or abandoned text, that would have benefited from revision. The first performance on record was not until 1674. Since then it has rarely been produced, never popular, often adapted or with the text doctored one way or another. The play is something of an ugly duckling. However, its major attraction lies in passages of incandescent verse, especially in the second half, when Timon vents his rage against ungrateful man [4.1]:

Matrons, turn incontinent,

Obedience fail in children! Slaves and fools,

Pluck the grave wrinkled senate from the bench,

And minister in their steads! To general filths

Convert o’th’instant, green virginity:

Do’t in your parents’ eyes! Bankrupts, hold fast

Rather than render back; out with your knives,

And cut your trusters’ throats! Bound servants, steal!

Large-handed robbers your grave masters are,

And pill by law. Maid, to thy master’s bed,

Thy mistress is o’th’brothel! Son of sixteen,

Pluck the lined crutch from thy old limping sire,

With it beat out his brains!

Other attractions are patchy. Elements of the story resemble a parable: some critics see echoes of Christ’s passion, especially when the persecuted Timon urges his creditors to ‘cleave me to the girdle… Cut my heart in sums… Tell out my blood…’ [3.4]. It has aspects in common with The Merchant of Venice, with its relentless focus on money. I was in Trevor Nunn’s 1991 production of Timon, which struck a powerful chord by being set in post-Thatcherite, money-obsessed Britain. Timon’s foolishness, abandonment, self-imposed exile and bitterness have powerful echoes of King Lear. In fact the play has been called ‘A poor man’s King Lear’ – a suggestion refuted by Michael Pennington, who prefers to call it ‘A rich man’s Timon of Athens’.

Michael loves the play and knows it intimately, having watched Paul Scofield’s performance nightly when he first joined the RSC playing small parts in 1965. Since then he has appeared in numerous starring roles for the RSC as well as co-founding the English Shakespeare Company with Michael Bogdanov. A great bonus in this interview is the impromptu masterclass he offers on the handling of Shakespeare’s texts. Away from the classics, I’ve had the pleasure of working with him on television, and of playing his father Billy Rice in a revival of Osborne’s The Entertainer. We met to record the following interview in London in January 2014, shortly before he left to perform Lear in New York.

Julian Curry: Timon of Athens has been called an unfinished mess of a text. The play has a ruined magnificence, nonetheless. Does that sound accurate?

Michael Pennington: Absolutely. I think people are too keen to apologise for it. I came across an interview with Simon Russell Beale the other day in which he was talking about Hamlet, and Lear which he was then playing, and also Timon. He said he could never forget a line of Hamlet, and he was sure he wasn’t ever going to forget a line of Lear, even long beyond the time he finishes doing it. Whereas he said he’d forgotten Timon completely, after two years. I was very surprised to hear that, with great respect, because I think Timon is unique. To me the style of it, the psychology of it, the manner of it is quite exceptional, and not just because it’s unfinished or rough, but I think it occupies a particular place of its own. I believe you do the play a great service to treat it as a unique piece, rather than something which is quite like King Lear, with echoes of Macbeth. The paradox is that it’s clearly unfinished or abandoned and put away in a drawer by Shakespeare. A lot of the first half consists of lines which are almost but not quite blank verse, and they suggest to me that if he’d gone over them again, he would have made them into coherent five-beat blank-verse lines.

You’re not mentioning any collaboration with Middleton.

I’m not so much interested in that. No doubt someone like Middleton did help him, and indeed they all worked by committee. But you can usually tell the difference, and I take the view that you always know when it’s Shakespeare. With The Two Noble Kinsmen by Shakespeare and Fletcher you know immediately which is which, by instinct as a performer. Scholars and academics analyse the text at length with word searches and all the modern tools. But you just hear the music. That may sound rather sentimental, but I think you do. When you’ve done a lot of Shakespeare you know when someone else is at work.

Given that Timon is a botched text, what did you do? Was it much cut or rearranged?

I think the thing that’s most obviously wrong (quote, unquote) with it is the second half, when Timon is in the woods or a hole in the ground or cave or wherever you put him. Despite the superb language it’s like a series of interviews with these people who keep visiting him. They all just exemplify the new state of affairs Timon is in.

I believe you tried rejigging the sequence in rehearsal?

We did. And we came to the conclusion it didn’t really matter what you did with it, because there isn’t a dramatic shape. Which means that Shakespeare really hadn’t worked it together properly. Now I’ll just pop in a theory of mine, which is that he abandoned the play because he realised what he was writing sailed close to King James’s court. That was a court in which, from what one knows of it, there was a great deal of sexual corruption, bribery, and a great deal of cash for official favours, with lobbyists everywhere. In many ways, Timon occupies the same kind of territory. And he, like James, has a kind of sexual ambiguity. So I think Shakespeare may have realised he was sailing a little too close to the wind. I’ll digress a tiny bit more, if I may.

Feel free.

In one sense the play seems to me to sit somewhere between Macbeth and Lear, because in Macbeth he was at pains to flatter James, to engage him. He writes about witchcraft, which James was much interested by. And he gives Banquo a complete makeover because in the original story he was one of the two conspirators: it was Banquo who conspired with Macbeth to kill Duncan, not Lady Macbeth. But of course Banquo was thought to be the founder of the Stuart dynasty, and James was his descendant, so Banquo had to be made good. Then you have the Porter’s reference to the ‘equivocator’ Henry Garnet, the Jesuit priest who was involved in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was tortured to within, well, less than an inch of his life by James. He was hung, drawn and quartered as plotter of regicide for refusing to reveal the secrets in the confessional, which of course were supposed to be sacred and confidential. There was much anti-Catholic paranoia at this point in James’s reign, which is interesting when you consider that Shakespeare himself may have been a crypto-Catholic. So I think his relationship with James must have been uneasy. There’s a certain amount of sycophancy because Garnet, the equivocator, is referred to in a hostile way by the Porter in Macbeth [2.3]. But Shakespeare is sort of swinging. He swings between pleasing James and slightly objecting. James was a great and generous patron, but I don’t think much about his court life can have appealed to Shakespeare. For instance, the actors were all made to dress up in red clothes and march in a procession when James first arrived in London.

Were they really?

Fantastic. Yeah. They were each given money to buy four and a half yards of scarlet cloth.

I wonder if I can lasso yo...