![]()

Roger Allam

on

Falstaff

Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 (1596–8)

Opened at Shakespeare’s Globe, London on 14 July 2010

Directed by Dominic Dromgoole

Designed by Jonathan Fensome

With Oliver Cotton as Henry IV, Sam Crane as Hotspur, William Gaunt as Shallow, Barbara Marten as Mistress Quickly, and Jamie Parker as Prince Hal

Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 were first performed in 1596–8, the source material coming mainly from Holinshed’s Chronicles. Many people consider them to be among Shakespeare’s very finest plays. With their astonishing breadth of scope they are outstanding examples of his genius for juxtaposing diverse dramatic elements. King and commoner, poetry and prose, town and country, war and peace, political strategy and the rumbustious low-life comedy of the tavern – all blend seamlessly into a rich dramatic entity.

The two plays can stand alone or as integral parts of Shakespeare’s cycle of eight English history plays, beginning with the deposition of Richard II in 1399, spanning the Wars of the Roses, and culminating with the death of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. The Royal Shakespeare Company was the first to perform all eight plays, under the umbrella title The Wars of the Roses, in 1964.

It is interesting to view them in the wider context, both for their historical sweep and for the development of characters. The two parts of Henry IV reverberate backwards to Richard II and forwards to Henry V, most notably in the theme of Bolingbroke’s usurpation of the crown. His remorse sets in the moment after Richard II’s assassination. That play concludes with Boling-broke announcing ‘I’ll make a voyage to the Holy Land / To wash this blood off from my guilty hand’ [5.6]. The vein runs through both parts of Henry IV and it is echoed by Henry V in his prayer before the Battle of Agincourt: ‘Not today, O Lord, / O not today, think not upon the fault / My father made in compassing the crown’ [4.1].

King Henry IV himself is hardly recognisable from the vigorous, confident and astute Bolingbroke of Richard II. Over the two plays he becomes increasingly frail and fretful, sleepless and haunted by his sin. He eventually dies, as sick in soul as in body. Conversely the upwardly mobile Prince Hal sheds his youthful playboy image, ruthlessly rejects Falstaff, and evolves into the dashing and heroic King Henry V.

Bestriding the action, literally like a colossus, is Sir John Falstaff. He is old, grossly fat, disgraced and totally unscrupulous. He eats, drinks, lies and steals, suffers from verbal diarrhoea and celebrates his way through life… when not snoring. He towers over both plays and is arguably the best loved and most colourful of all Shakespeare’s great characters. He appeals as rogue, wit, anarchist, reprobate, life force, raconteur, bon viveur, philosopher. Even his cowardice is endearing. His final rejection by Prince Hal ends Part 2 on an almost unbearably harsh note: ‘I know thee not, old man. Fall to thy prayers. / How ill white hairs become a fool and jester!’ [5.5]. However, such was his popularity that, according to legend, Queen Elizabeth begged Shakespeare to bring him back, resulting in The Merry Wives of Windsor. The critic A.C. Bradley wrote ‘In Falstaff, Shakespeare overshot his mark. He created so extraordinary a being, and fixed him so firmly on his intellectual throne, that when he sought to dethrone him he could not.’

Both plays have large casts with a wide diversity of characters. Opposing the Lancastrian King Henry IV and his army are the Yorkist rebels led by Harry Hotspur, an individual so fiery and charismatic that young leading actors have often chosen to play him rather than Prince Hal. The dotty old justices Shallow and Silence, reminiscing in their Gloucestershire orchard, are glorious original creations. There is also a gallery of colourful smaller roles. Francis the tavern drawer who says little but ‘Anon, anon, sir!’ can be fun to play, as can Falstaff’s country bumpkin army recruits. My only involvement in the Henrys was as the warriorlike Earl of Douglas in an undergraduate production with the Cambridge Marlowe Society. As a fresh-faced nineteen-year-old from Devonshire, I was ill-equipped to play the ‘hot termagant Scot’ [5.4]. I wore a ginger wig and big bristling beard in an effort to look butch and fearsome, and struggled with the accent. The director John Barton did his best to squeeze highland ferocity out of me. We worked tirelessly until the line ‘Another King? They grow like Hydra’s heads!’ came out, as I recall, something like ‘Yanitherrr Kung? Tha-grrroo-lak Heedrrra’s heeds!’

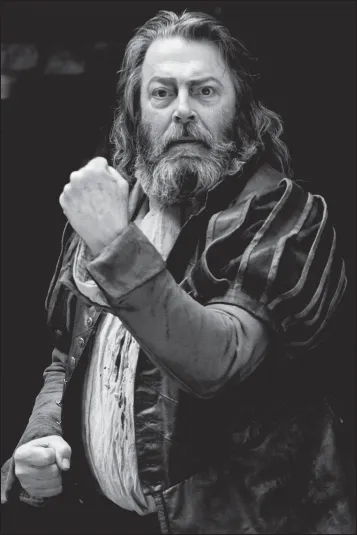

Roger Allam had a huge success when he played Falstaff at Shakespeare’s Globe in 2010. His performance won that year’s Laurence Olivier Award for Best Actor. I interviewed him at his home in South-West London the following year. I discovered that Roger is not only a superb actor but a fine cook, who effortlessly rustled up a very tasty lunch before our talk.

Julian Curry: You’ve done a lot of Shakespeare. How do you rate these two plays?

Roger Allam: They’re amongst the very finest, I would say, some people think the finest. You get such a broad canvas, with a wonderfully complete picture of England: the court and the countryside, the rebels, the aristocracy and the low life of the tavern. Even the smallest parts are written with reality and humanity, they’re magnificent. And the Shallow and Silence scenes in Part 2 are almost Chekhovian.

What was it like working at the Globe?

I’d been one of those people who was instinctively against it, I guess due to having spent a long time with the RSC, where they became quite neurotic about the Globe.

Why was that?

There was the notion of it being kind of ‘thatched cottage’ Shakespeare – I remember that phrase being used – and anti-intellectual. I suppose the same kind of suspicion happened in music when it became fashionable to play authentic period instruments. So I wasn’t enormously sympathetic to it as an idea. I went to something in the first season that I thought was utterly awful and confirmed all my prejudices against the Globe, and I never went again. In retrospect that was rather foolish, because I missed a lot of Mark Rylance’s work, which I now wish I’d seen. I didn’t go again until the year before I played Falstaff, when I saw a friend of mine in Trevor Griffiths’s play [A New World] about Tom Paine. And I was very impressed, particularly with the audience they’d built up. This slightly rambling play, which I think had been adapted from a film script, was packed with 1,500 people watching it.

That’s the capacity of the Globe?

Yeah. And they were really lively. I thought: My God, if you put this play on in the Olivier auditorium at the National it would empty the place. One of the things Dominic Dromgoole has done tremendously well is to start commissioning and encouraging authors to write for that space, to build up a repertoire.

So they do other work besides Shakespeare?

Well, they do at least one, possibly two new plays a year. It’s brilliant, because it means writers can have quite a large cast, which they don’t often get at other addresses. It stops the place becoming purely a Shakespeare house. And it helps writers, I suppose, to examine a more Shakespearean style.

There’s no artificial lighting, so you have to perform in daylight. Was that a problem?

No, actually, no. It’s something you get used to. Of course it means you can’t achieve all the effects you can in other theatres, such as standing in a spotlight surrounded by darkness doing your soliloquy. But you’re always engaging with the audience. After seeing that Trevor Griffiths play, when they offered me Falstaff I realised it’s the perfect part to play there, because he never stops talking to the audience. Another great thing about the Globe is that you can get in for a fiver if you’re prepared to stand, and that’s half of the house. Seven hundred people pay five pounds. There’s no other theatre like that in the land. You get a totally different feel when there are seven hundred enthusiasts. Well, of course they’re not necessarily all enthusiasts, because the other great thing about it only costing five pounds is that people who might not be normal theatregoers can think: Well, I’ll just pop in and see whether it’s any good or not, and I can bugger off if I don’t like it! And that’s wonderful. I’ve quite frequently kept my seat in the stalls because I’ve thought: This has cost me fifty quid, so I’ve got to stay! The only drawback to that theatre is the placement of the pillars, which are a permanent fixture. There’s nowhere you can stand on the stage where every single person in the audience can see you. Absolutely nowhere. So really, I guess, the pillars should be six or eight feet further upstage.

What was the weather like during your production?

We were quite lucky, we only had two really bad days. There was one afternoon when Ian McKellen came to see Part 1, and it just rained and rained and rained from beginning to end. Amazingly there were still two hundred groundlings, as they’re called, in the pit.

Was that the time when you segued into King Lear’s ‘Blow winds and crack your cheeks’?

No, that was the press show, which was also torrential.

A part which spans two plays is quite a luxury, isn’t it? Gives you a longer journey.

Yes, I guess so. Actually you’re not so much aware of that because you just think: Well, there’s Part 1 and then there’s Part 2, which is such a different beast. Part 1 has a natural momentum that Part 2 lacks.

Did you rehearse both plays at once, or singly?

At first we rehearsed both at once, then we left Part 2 alone and got Part 1 ready to open. While we were previewing Part 1 we went back t...