- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

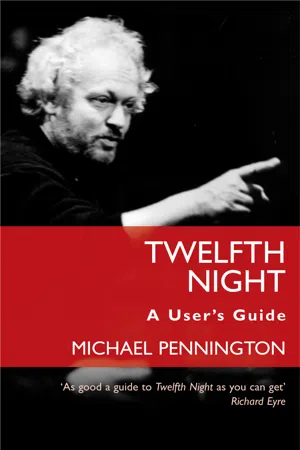

Twelfth Night: A User's Guide

About this book

' As good a guide to Twelfth Night as you can get ' Richard Eyre

This serious yet lively book offers an intensely practical account of the way Twelfth Night actually works on stage.

Drawing both on his inside knowledge as a director of the play and on his lifelong experience as a Shakespearian actor, Pennington takes the reader through Twelfth Night scene by detailed scene.

'He is sharply intelligent, scrupulously careful, hugely knowledgeable and above all, wonderfully readable' Peter Holland, The Shakespeare Institute

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

ACT ONE

1.1. He starts with the authority of a king but with a rather unkingly instruction:

If music be the food of love, play on . . .

This is Orsino, though it will be some time before we learn the name. We could be indoors or out, by day or by night: a concert is in progress, and there has been a pause between items. Orsino clearly expects a lot of the occasion:

Give me excess of it, that, surfeiting,

The appetite may sicken, and so die

– which seems tough on his musicians, who are likely to be practical people. His words are smooth, but his feelings, clearly, less so: he wants the beautiful music not for its own sake but to kill off a painful need.

The players count themselves in and start again – but then Orsino notices something and tells them to go back a little:

That strain again; it had a dying fall . . .

It is another difficult order. The musicians confer, decide from which bar to start, then get going in unison once more – whereupon they are stopped altogether:

Enough, no more;

’Tis not so sweet now as it was before.

What a life.

There is another way of doing it, and it is less absurd. Orsino’s opening line could be a grand cue for the beginning of the concert, and ‘that strain again’ not be an order at all, but his quiet appreciation of a phrase as it is repeated in the tune. In this sweeter version, many silences lap around the lines for the music to play in, and the musicians don’t have to keep stopping and starting. In fact, you hardly notice them, but get a strong impression of the romantic hero, languishing in the appropriate key. If the musicians’ dilemmas made for a little comedy the first way, this is a rhapsodic colour-wash.

Satire or stardust, or how much of each? In this play, the choice will present itself every few minutes.

Either way, Orsino’s abrupt order marks the end of the beginning, and in the silence all attention swings onto him. He will surely explain himself, and begin a story: but instead, he apostrophises about the ‘spirit of love’. It is, for him, ‘quick and fresh’, but it also strips all value out of everything it touches:

. . . notwithstanding thy capacity

Receiveth as the sea, nought enters there

Of what validity and pitch soe’er

But falls into abatement and low price

Even in a minute.

You cannot help noticing that the romantic image has ended commercially, with a hint of sexual waste. Orsino expressed it gracefully, but the fact is that he is paying a price for his passionate surrender: expense of spirit, disappointment, a bankruptcy in which even sweet music sounds like the rattling of tin cans.

A second voice offers to help. Curio might be one of the musicians, a courtier or a friend. Sturdily he suggests a bit of exercise, as one might a cold shower; but, poor man, he is subjected to a lordly quibble:

CURIO: Will you go hunt, my lord?

ORSINO: What, Curio?

CURIO: The hart.

ORSINO: Why so I do, the noblest that I have.

O when mine eyes did see Olivia first,

Methought she purged the air of pestilence . . .

O when mine eyes did see Olivia first,

Methought she purged the air of pestilence . . .

It seems that not only does Orsino do most of the talking here, but he is able to turn everything to self-pitying advantage. However, the reason for his storminess has at least been named: Olivia. It is a relief – perhaps this is to be a love story between real people after all. But Orsino has not finished with his contraries: this woman is benevolent enough to destroy disease in the air we breathe,1 but she also provokes a chase to the death – in fact violence within oneself, because at the sight of her he was divided into two, his own hunter and quarry:

That instant was I turned into a hart;

And my desires, like fell and cruel hounds,

E’er since pursue me.2

Abashed, Curio withdraws into the shadows and will barely speak again.

Silence once more, and perhaps some embarrassment. Is Orsino always like this, speaking in a style that nobody can find the right way to respond to? Perhaps he wildly overstates his mood for poetic purposes, perhaps his torment is real. Fortunately, there is a new arrival, Valentine, as deferential to him as Curio was, but hiding who knows what thoughts of his own:

ORSINO: How now, what news from her?

VALENTINE: So please my lord, I might not be admitted;

But from her handmaid do return this answer . . .

But from her handmaid do return this answer . . .

His practicality freshens the air, as if the sun was rising and the windows being opened a little. He sounds like a civil servant mortified by a foolish mission but taking it on the chin: at least he is trying to reorganise the disarray. Although he speaks poetically, as a compliment to Orsino, it is in a much simpler style; and again, there is an acting choice to be made, between irony and romance. What Valentine says may be a tactful dressing-up of a blunter message he has been given at Olivia’s house – to go away – or a direct quotation carefully memorised. If the second, we seem to be in a world in which everyone sings in the same key, a handmaid offstage sounding as good as Shakespeare; if the first, the euphemistic spin is quite comic:

The element itself, till seven years’ heat,

Shall not behold her face at ample view;

But like a cloistress she will veiled walk,

And water once a day her chamber round

With eye-offending brine . . .

Imagining Valentine and the handmaid in a little huddle, whispering at Olivia’s front door, we get a distant glimpse of the woman Orsino confusedly celebrates, and she seems as self-conscious as he is.

Explaining her seclusion, Valentine is incredulous, and can’t help adding a discreet comment of his own:

. . . all this to season

A brother’s dead love, which she would keep fresh

And lasting in her sad remembrance.

The stupendous use Orsino makes of the bad news is a tribute to his abandon and resourcefulness. He is not at all interested in the dead brother, but it strikes him that if Olivia will sequester herself like this for him, how passionately will she commit herself to her man when finally ravished by the ‘rich golden shaft’ of his love – an event now somehow taken for granted. Perhaps he needed the flat rejection to animate him, for his confidence is suddenly as great as was his wallowing despair. Now his love will kill

the flock of all affections else

That live in her . . .

– and he will be king by violent conquest of her every function, ‘liver, brain and heart’. It is a lover’s magnificent ace, breathtaking for his companions, who are ordered to run off ahead of him to lie down on beds of flowers. Or is it just a metaphor? All this poetic one-upmanship could try the patience of a footsore courtier.

As they go, questions hang in the air: it is not so much that we want to know what will happen next as to get some purchase on what we have seen, since Orsino’s lofty form of speech has provided few bearings. Twelfth Night has certainly announced itself: one way and another, music and love will dominate the proceedings. But there is hardly any plot information (as there is in King Lear or A Midsummer Night’s Dream), few brooding atmospherics (Hamlet), and certainly no Chorus – nothing that offers a glimpse of some real world beyond the words. This short opening scene has left us as suspended as the musicians.

Already I have declared a preference, I suppose. Orsino’s paradoxical style is certainly typical of a particular kind of Eliza bethan wit and poet, but it also seems neurotically self-regarding. For all its lyrical swing, the language works in uncomfortable opposites – love, food and music immediately get mixed up with nausea, surfeit and death; and the images – violets, perfume and melody – are rather promiscuous. In the end, he tetchily rejects the whole clutter. How seriously should he be taken? He seems to have found a kindred spirit in Olivia: to seclude herself for seven years is to push sorrow past the point where it might properly die, just as Orsino is forcing himself beyond the human need for rest.

For the actor, the first of his (only) four scenes contains a large ambush. Probably cast for his rhapsodic abilities, he needs to add to them the flashy skills of the quibbler, and to handle a heave of feelings wholeheartedly. Most trickily, the neurosis has only tunefulness with which to express itself – it comes out not with the jaggedness of Stravinsky but with the opulence of Rachmaninov. Around him is a series of apparently thankless parts; but, although he has absorbed most of the oxygen, this is, in a limited way, an ensemble piece. Curio’s entire role was hostage to a poetic conceit and Valentine was just the fretful messenger, but we will have watched them keenly for orientation – and we specially tried to see Orsino through the eyes of his patient musicians.3 It is a truism in the theatre that we believe someone is a king, and what kind of a king, not from his own behaviour but from the attitude of those around him – so their precise reactions will count for a lot. Even so, we don’t quite know where we are or how to take anything: powerful emotions are in the air, but for some reason we want to laugh. The first line of the next scene is like a discreet joke.

1.2.

‘What country, friends, is this?’

The stage seems to widen and deepen. A woman with the remnants of her belongings, and some sailors – and a gravity in them, as if being here brought them no ease but they are undaunted. The man’s answer is a first moment of summary:

This is Illyria, lady.

The woman called them ‘friends’, and to this Captain she is ‘lady’: these are the first people to pay each other proper attention.

The new landscape is hardly conceivable beside Orsino’s – wind scurrying along a beach in front of an infinity, the suspended, baleful light that follows a storm, these tiny figures.4 They speak a soft and steady verse – the lines full of light where Orsino’s were congested, lucid where his jostled for scale and meaning. The melodiously-named country is counterpointed straight away with the fabulous home of the blessed, but the real name sounds no more substantial than the mythical:

VIOLA: And what should I do in Illyria?

My brother he is in Elysium.

My brother he is in Elysium.

If we have settled, it is only on sand. However, there has been a real tragedy, in contrast to the romantic martyrdom of the distraught lord in his court:

VIOLA: Perchance he is not drowned; what think you, sailors?

CAPTAIN: It is perchance that you yourself were saved.

Orsino compared the ‘spirit of love’ to an ocean that reduced its victims to ‘abatement’: but this is the real thing, an elemental force destroying and restoring at will.5

For the first time too, one character adapts to the needs of another: having dismissed the possibility of anyone else surviving the shipwreck, the Captain is touched by Viola’s forlorn hope

O my poor brother! And so perchance may he be

and changes his story for her benefit. The two of them embark on a gentle and respectful game, watched, rather like Orsino’s musicians, by a handful of sailors who keep their views to themselves. The Captain borrows Viola’s elevated vocabulary:

I saw your brother,

Most provident in peril, bind himself . . .

To a strong mast that lived upon the sea,

Where like Arion on the dolphin’s back,6

I saw him hold acquaintance with the waves

So long as I could see.

This heroic pictorialism – like an illustration to Captain Hornblower – drops a hint: is he telling the truth? Perhaps, like Valentine with Orsino, he is dressing bad news up a bit. Viola sees his glorious simile for what it probably is, rewards the performance:

For saying so, there’s gold

and colludes:

Mine own escape unfoldeth to my hope,

Whereto thy speech serves for authority,

The like of him.

The fragile picture fades away. What more is there to say? H...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One

- Entr’Acte

- Part Two

- Conclusion

- About the Author

- Copyright Information

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Twelfth Night: A User's Guide by Michael Pennington in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism of Shakespeare. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.