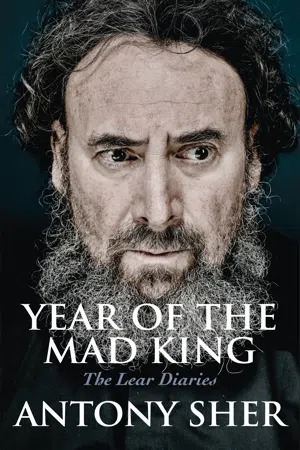

![]()

1. The American Lear

Wednesday 27 May 2015

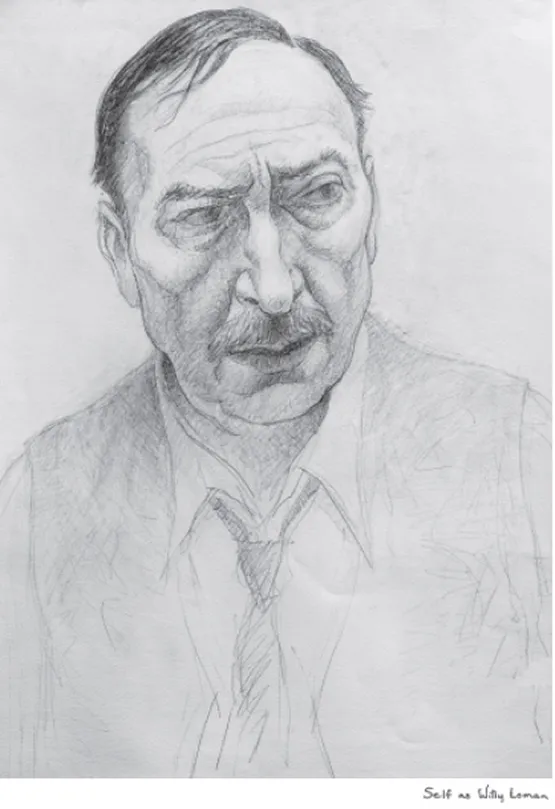

He’s known as the American Lear.

Willy Loman.

But are they really alike?

I’m about to find out…

These thoughts occur as I stand in the kitchen of our London home, wearing my dressing gown, my eyes still sleepy, my hair a tangle of thin strands – it’s from all the Brylcreem I put into it for last night’s show. I’m currently in Death of a Salesman at the Noël Coward Theatre, playing Willy Loman, and he has a shiny-neat, sharply parted 1940s haircut.

Meanwhile, my hand is resting on a script from the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Literary Department: King Lear.

I’ve been pestering Greg (Doran; RSC Artistic Director, and my partner) to arrange for the text to be typed up into this A4 format, so that we can both mark up some suggested cuts for the production scheduled for the second half of next year. It may be a long way ahead, but I’ll need to start learning the lines quite soon.

Greg was asleep when I got home from the theatre last night, and he had to drive up to Stratford early this morning, so he’s left the script on the kitchen table, with a note: ‘This is yours.’

He just means, ‘This is your copy’, but it could read as, ‘This is a part you should play, and we’re doing it now.’

In fact, we’ve been talking about the play for years, as one of our Shakespeare collaborations: Titus Andronicus, The Winter’s Tale, Macbeth and Othello, with the surprise addition in 2014 of Henry IV Parts I and II. But it’s one thing to talk about doing King Lear, and another to actually touch the script on your kitchen table on a bright May morning.

I feel lucky.

Older actors queue up to play Lear like younger ones do for Hamlet, and if they want to perform these roles at the RSC or the National, it’s not easy to get into the queue at all.

So despite all the years – no, decades – that I’ve spent working for the RSC, I still feel lucky that I’m going to be playing Lear there. And I’d never have imagined, when Greg and I first discussed the idea, that he’d be running the company when we finally came to do it.

Ahead is a hectic schedule. Salesman runs till July, then Greg directs Henry V, then the company revives the Henry IVs and Richard II (starring David Tennant), and plays the whole tetralogy at the Barbican, and then we take it on tour, to China and New York.

And then we do King Lear.

If I’m still standing.

Saturday 30 May

In between the matinee and evening shows of Salesman today, I went for a little stroll. Found myself heading towards the Pastoria Hotel in tiny St Martin’s Street, just off Leicester Square. This is where, having just arrived from my native South Africa, I spent my first ever night in the UK. It was Wednesday 17 July 1968, and my parents and I were to stay there while I auditioned for drama school.

Performing Willy Loman eight times a week is proving to be exhausting, and I was hoping that seeing the Pastoria again would wake me up to the big journey I’ve made – from being a teenage guest in that hotel to a leading actor in a neighbouring West End theatre. But I found the building covered in scaffolding and plastic sheeting. The renovation was unsightly, and didn’t give me the boost I needed. And Leicester Square itself was rather intimidating, with huge crowds, a gang of chanting football fans, and bouncers outside every bar and restaurant. This was the real West End, very different to the sedate and cultured atmosphere of the Noël Coward Theatre. I scurried back to its safety.

Preparing for the evening show, sitting in front of my dressing-room mirror, I was putting fresh Brylcreem into my hair when I started thinking about Willy Loman and Lear again.

I’m not sure the term ‘the American Lear’ means there are profound links between the two characters – it was probably just coined by actors to express the fact that the roles are, arguably, the most challenging that exist in British and American drama. Yet, now that I’ve got both in my sights, I can detect some traits which they do actually share.

A surprising consonance is that although one is a nobody, a failed salesman, and the other a powerful king, they both have a similar way of imposing their will on others, especially their families. They both have something monstrous in them.

Discovering Willy’s monstrous side was a major breakthrough for me during rehearsals. He is so iconically a victim figure – the little guy weighed down by two suitcases of merchandise he can no longer sell – that my performance was becoming hushed, self-pitying and passive, which simply didn’t drive the play the way it needs. I kept talking this through with Greg, who was directing, but no solution was immediately apparent.

Then I read a passage in Arthur Miller’s autobiography, Timebends, and Willy Loman was never to be the same again. Miller is describing one of his uncles, Manny Newman, who was a possible model for Willy. Uncle Manny was also a salesman, also had two sons (one of whom, like Biff in the play, excelled at sport, but not school studies), and also ended up committing suicide. Miller writes of Uncle Manny:

‘He was so absurd, so completely isolated from the ordinary laws of gravity, so elaborate in his fantastic inventions… that he possessed my imagination. Everyone knew his solution for any hard problem was always the same – change the facts.’

And of Uncle Manny’s home:

‘In that house… something good was always coming up, and not just good but fantastic, transforming, triumphant. It was a house without irony, trembling with resolutions and shouts of victories that had not yet taken place, but surely would tomorrow.’

This is the Loman household, and Willy is Uncle Manny: absurd, defying the laws of gravity, changing the facts, shouting with victory.

Suddenly Willy stopped being a victim. He’s a fantasist, a bully. Except that Miller’s masterstroke is to offset these flaws by showing us Willy’s place in society. He’s lost in the modern world, he’s being destroyed by it. We watch this happening, step by step. As Willy goes under, and as he continues to boast and bullshit, the more it breaks our heart.

This has never happened to me before – a playwright guiding me towards a character not just through the play, but a completely separate piece of writing: his autobiography.

Shakespeare does not offer the same help. Autobiography, auto-shmiography. If we know hardly anything about the Bard’s life, we know even less about the other people in it, people who might have inspired his characters. Imagine if there was an Uncle Jack who was the model for Falstaff, and an Uncle Lee the model for Lear…

Monday 1 June

It’s June but could be November. Cold, wet, windy. I’ve lived in England for forty-seven years now, so why does the weather still continue to surprise and appal me?

Never mind – I’m holed up in my warm study, with a little stack of Lear scripts on my desk.

I want to try reading it afresh, despite the fact that I know it well. It has cropped up rather frequently during my life in this country…

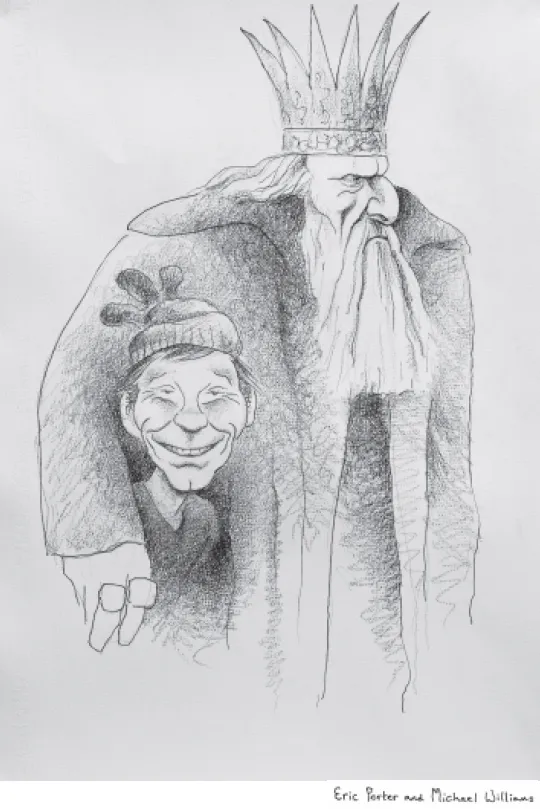

1968. On the first weekend after we checked into the Pastoria Hotel, my mother joined me on a special pilgrimage to a place which held mythic status for me. Stratford-upon-Avon. I was finally going to see the Royal Shakespeare Company in the flesh, and in action. We would have happily watched anything that was in their current repertoire, but the play at that Saturday matinee performance happened to be King Lear. Directed by the RSC’s new Artistic Director, the twenty-eight-year-old Trevor Nunn, and starring Eric Porter. In the first scene, Lear was carried in on a litter, and all the courtiers abased themselves, as if to a god. I was immediately on the edge of my seat, and I don’t think I sat back for the next few hours. I had never seen theatre like this. I remember the design was very dark, with a strong use of chiaroscuro: figures lit in the surrounding blackness, Rembrandt-like. I remember Norman Rodway as Edmund – his effortless amorality. I remember Alan Howard as Edgar, and the shock of his near-nakedness in the storm scenes (exposing what I was later to hear Terry Hands describe as ‘the strongest thighs on any Shakespearean actor’). Most of all, I remember Michael Williams as the Fool, his face frozen in the mask of Comedy, his heart visibly breaking. I’m afraid I don’t remember much about Porter himself. Years later when I worked with him (Uncle Vanya,National Theatre, 1992) he said that it was an unhappy and unsuccessful production. What? – but it was a revelation to me. Later, Tim Pigott-Smith (who talked to Porter about it when they worked on The Jewel in the Crown) told me that Porter simply resented having a young upstart as his director.

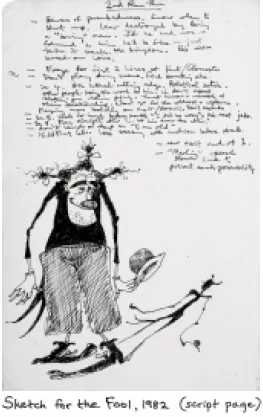

1972. My first proper job as an actor was at the Liverpool Everyman, and my first show there was King Lear, directed by the company’s great Artistic Director, Alan Dossor – though by Everyman standards it was a very conventional production. An Australian actor, Brian Young, was too young for Lear, Jonathan Pryce was electric as Edgar, and I was the Fool. Inspired entirely by Michael Williams’ performance, I tried to make the character both funny and tragic. He became a scruffy little figure in a huge overcoat, with a slight underbite which gave an unintentionally goonish sound to anything he said. He was being laughed at, as much as with. This suited the cruelty of the play.

1982. When I began my career with the RSC, it was again playing the Fool in King Lear. Adrian Noble directed a brilliant, anarchic production, and Michael Gambon was the best Lear I’ve ever seen. The Fool didn’t just have an underbite now, he was disabled, hobbling about on inward-twisted feet. But he also had a red nose, a white-painted face, a battered bowler hat, and carried a miniature violin which he couldn’t play. He and Lear did little routines together – a ventriloquist act, a front-cloth act – and later, still together, they were plunged into the chaos of the storm. It ended with Lear accidentally stabbing the Fool to death in the mock-trial scene. (Hence explaining the Fool’s mysterious disappearance from the play.)

Today, sitting in my study, I put aside the A4 text from the RSC Literary Department. That only has the dialogue, but to fully understand the play, I’ll need help from the editor’s notes in one of the published editions. I look at my script from the 1982 production. We didn’t get issued with A4 typed-up scripts then, and mine was the old Arden edition, with a beautiful portrait of Lear in his crown of flowers on the cover (done by the artist Graham Arnold, a member of the Brotherhood of Ruralists). I open it. No good. It’s full of my sketches – of Adrian, Gambon, the rest of the cast, and my efforts to work out what the Fool might look like – and there are scribbled notes, and my lines are underlined in red. All this would be distracting.

I pick up another edition, the RSC’s own, edited by Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen. I start to read the Introduction. It quotes Charles Lamb:

‘The Lear of Shakespeare cannot be acted. The contemptible machinery by which they mimic the storm… is not more inadequate to represent the horrors of the real elements, than any actor can be to represent Lear.’

I lower the book, sighing.

Well, nobody said this was going to be easy. After all, Lear is known as the Everest of Acting.

I’m always surprised that people think that the creation of a character happens in rehearsals, and that rehearsals happen a few weeks before the show opens. Not so. Impossible, in fact, with Shakespeare’s major roles. The RSC may regard the beginning of King Lear rehearsals as 20 June next year, but for me the beginning of rehearsals was today.

Tuesday 2 June

Verne (my sister) rings from South Africa. She’s had bad news. When she went for her fortnightly chemo treatment yesterday, they couldn’t give it because her blood count was too low.

Verne was diagnosed with terminal cancer (of the colon and liver) last August. After the initial shock, which went through the family like an earth tremor, there was another surprise. The specialist gave his estimation of how much time she had left: six months without chemo, eighteen months with chemo.

That was almost a year ago, and a worrying new development is the situation with her blood count. Sometimes it’s too low for chemo, sometimes it’s okay.

Is this ‘the next stage’? Leading to ‘the final stage’, where they can no longer give chemo at all?

I try not to think about it.

R...