![]()

Chapter 1

From a Dilemma to a Delightful Solution: Making Maternity Skirts Fit

Popular belief suggests that in previous centuries women secluded themselves during pregnancy. However, a closer examination of the lives of women and their clothing indicates that this was not always the case.1 As early as the fourteenth century, artists depicted the pregnant Madonna and other women wearing the clothing of the era. Although these dresses were not maternity clothes, they were garments altered for a pregnant body. Giotto, one of the finest artists of the late Middle Ages, who introduced a new style of art that accurately represented scenes, included pregnant women in his art. His women wore garments gathered under the bust that were divided on the sides, showing their undergarments. Two centuries later, when women wore short bodices with flowing skirts, they looked pregnant whether they were or not.2 Even a review of artwork created from the beginning of the 1700s through the early nineteenth century indicates that pregnant women were often included in group scenes depicting urban settings. Perhaps only with the advent of the Victorian era did women become reclusive while pregnant. Moreover, the belief that women secluded themselves during pregnancy would only be true of the more affluent women, since women who were less affluent would need to work—pregnant or not.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries many middle-class women supervised their homes or managed, along with their husbands, small commercial establishments. These women were unable to remain secluded multiple times during their numerous pregnancies. In some instances they trekked around town doing the business of the household, and they continued to entertain while pregnant. For example, the nature of life in villages or towns required women to go to the market or to deal with customers if the husband was away. Moreover, when one considers that many of these women were often pregnant for half the time between marriage and middle age, it is understandable that they continued their daily activities throughout their pregnancies. Even those women of higher status who could have remained secluded because they had servants to make necessary purchases did not forgo daily activities. Because these women continued to participate in regular daily life, they needed clothing that was altered or made especially for maternity wear.3

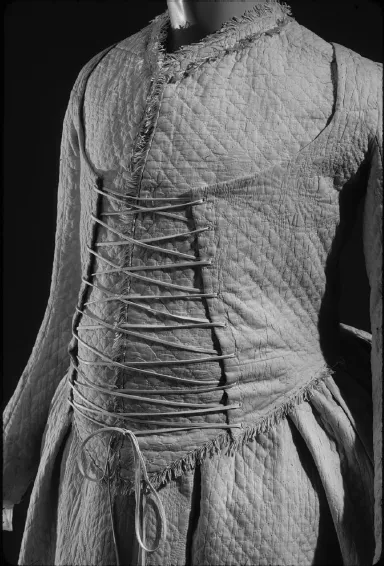

Even though women needed clothing to cover the pregnant body,4 often the clothes were not necessarily created solely for maternity use. During the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth century textiles were quite expensive, and garments were often altered from year to year, season to season, or for use by the pregnant woman and then back for the nonpregnant woman. Linda Baumgarten's study of late eighteenth-century women's clothing indicates that many garments were either created with extra material or panels so that the garments could be let out, or else they were made in a way so that one part of the garment could be enlarged or changed for various uses. For example, a peplum could be widened or created with pleats to cover the increasing size of the abdomen. Often side seams were cut with extra fabric so that the garment could be made larger to accommodate the increased girth of the pregnant woman. Some women solved the problem of the expanding body by wearing “bedgowns” under a larger waistcoat or apron. The bedgown was a loosely fitted dress that could serve as a nightgown or undergarment but was also used as part of the maternity wardrobe. In some instances women, especially those who worked in a shop, used these loosely fitted garments along with an over-garment similar to a jumper or apron. Other women solved the problem by wearing “waistcoats” or vests that were laced in both the back and front. The laces could be let out or taken up to accommodate either the pregnant or the nonpregnant body. Additionally, some garments had extra fabric under the armholes so that a pregnant woman or nursing mother could accommodate larger breasts.5

With the advent of the power loom and later the sewing machine, textiles and then ready-made clothing were less expensive and more readily available, and even custom-made dresses were less expensive than they had previously been. Middle-class women could afford dresses that changed when the fashions changed, and they could afford dresses created for various specific uses. Thus, they could also make or purchase dresses that were comfortable during the times that they were pregnant. Nevertheless, the dilemma of the expanding body and how to cover it remained a constant problem.

While Linda Baumgarten argues that women during the eighteenth century continued their activities and participated in both social and commercial events during their pregnancy, Rebecca Bailey suggests that, due to medical advice and changing cultural norms, pregnant middle-class women in the second half of the nineteenth century often decreased their activities and lived secluded lives. But these women still needed maternity clothing for use at home, and several specific design problems remained unsolved. The first problem was how one comfortably allows for the expanding abdomen, and second was how one keeps the dress or skirt from appearing shorter in the front when it hikes up as it covers the growing abdomen. These problems are the same whether one is creating a one-piece dress hanging from the shoulders or a two-piece outfit with the skirt hanging over the abdomen.

Lace-up vest from Colonial Williamsburg, early eighteenth century. Reprinted by permission of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Museum Purchase.

These problems were exacerbated after the turn of the twentieth century as fashion and women's lives began to change. Whereas during most of the nineteenth century women wore fashions that were created with many layers of fabric and also used excessive yardage in the designs, in the twentieth century fashion designs began to hug the female form. Women also began to discard the multiple layers of undergarments that had been popular in earlier decades. Also, as the Victorian era waned, time-saving devices and the advent of electric appliances made housekeeping less time consuming, and more women became involved in various activities outside the home. Some even began to work out of the house, and each of these activities increased the need for more garments. In addition, the expansion of the middle class created an increasing demand for ready-made clothing.6 However, ready-made maternity dresses were difficult to find.

In 1904 Lena Bryant became perhaps the first designer and manufacturer to market maternity clothing. Bryant borrowed funds from her family to establish her business, and when she went to the bank to open an account with these funds, the bank misspelled her name. The misspelling stuck, and her business became Lane Bryant. Bryant made individual dresses and hung them up for sale, displaying them as if they were ready-made outfits. Her first experience in designing maternity clothing came when she received a request to make a maternity dress that was “practical for entertaining at home.”7 This request encouraged seamstress Bryant to include maternity dresses in her line of ready-made garments. Rebecca Bailey suggests that eventually Lena Bryant dropped her maternity line as her business grew and she became the first clothing manufacturer specializing in clothing for the fuller-figured woman, now known as Lane Bryant.8 However, a close examination of newspaper advertisements that appeared between 1920 and 1950 indicates that Lane Bryant continued to manufacture maternity garments into the 1950s. These garments, though, were not created for the upscale market. For example, in 1937 Lane Bryant advertised three maternity dresses that ranged in price from $3.95 to $6.95.9 The advertising copy stated that all three dresses did their “clever bit to reapportion the figure, all have concealed adjustable features.” But all were dresses that either wrapped around the body or hung from the shoulders.10 Thus, although Lane Bryant was manufacturing maternity dresses, the company had not solved the problem of the expanding abdomen and the uneven hemline.

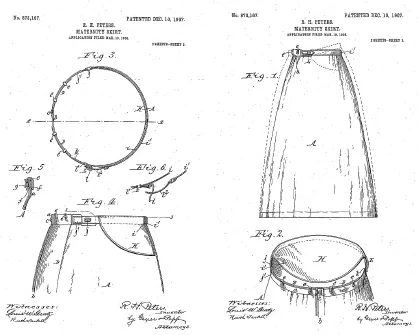

The problem of how to cover the pregnant abdomen became more pronounced as the twentieth century progressed and skirts got shorter. Perhaps one of the first inventors to try to solve these problems was Robert Peters. In 1907 he applied for and was granted a patent for a skirt that he claimed would solve the problem of maternity skirts. His skirt “contained no drawstrings or lacings,” but it could be adjusted to fit the expanding waist of the wearer. The Peters skirt pattern had a fabric-covered waistband made of spring steel that was divided into two parts. The parts wrapped around the waist and overlapped on the sides. The two pieces were held in place by a system of multiple metal hooks and eyes. As the waist enlarged the woman could move the hooks so that they could loosen the garment. Peters's invention also offered a way for the band to rise above the actual waist because the front section of the metal band could swivel up, arching over the abdomen. This band could be enlarged, but it remained rigid around the body, like a metal belt. To compensate for the change in skirt length as the front section of the band was raised above the abdomen, an oval panel with a flap extension of fabric was attached to the top front of the skirt.11 Although in theory Peters's patent solved the problem, his design did not become the standard in maternity wear. First, not many women would have wanted a steel band hooked around their waists, especially when they were pregnant; moreover, there is no proof that Peters ever converted his idea into an actual salable garment or that he profited from his invention.12

Patent 873,167 of 1907

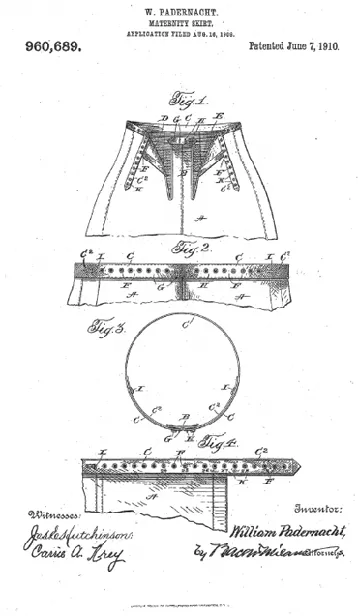

Two years after Peters's invention was patented, W. Padernacht obtained a patent for another adjustable skirt. This skirt had two parallel vertical slits and a band that could be adjusted with hooks folded into grommets. Each V-shaped slit could be widened as the abdomen enlarged. But this skirt patent did not include an upper garment so there was no corresponding plan to conceal the openings created by the slits.13 Various designers or inventors continued to apply for and be granted patents for maternity clothing throughout the next few decades. A dress patent was granted in 1916 that included a wraparound empire-line garment with an expandable waist. But this garment, like the others, did not solve the problem of the hiking hemline.14 Two more skirt patents were issued in 1919, and during the mid-1930s the U.S. patent office issued two more patents for maternity dresses. Yet, because each of these garments hung from the shoulders with various forms of adjustments around the waist, neither solved the problem of the skirt hiking up over the abdomen, which caused the front section of the skirt to look shorter than the back.15

The manufacture and sale of all ready-made clothing slowed when the Depression hit, leaving unsolved the problem of how to cover the pregnant woman's body. Additionally, the Depression lowered the birthrate, decreasing the demand for maternity clothing. For women who were pregnant during the Depression, “a single style was made to serve” multiple situations.16 During the 1930s, when women did shop for garments to wear when they were pregnant, they usually purchased dresses in larger and larger sizes, or they opted to wear a Hooverette, a wrap dress with two panels crossing in the front. These panels were cut so that they would cover the front but could expand across the enlarging abdomen. Neither of these options was satisfactory since the larger dresses had larger arm openings, sleeves, and shoulders, and bigger sizes were also generally longer from shoulder to waist and from waist to skirt bottom; thus they created a dowdy and unkempt appearance. The Hooverette had no waist and hung vertically from the shoulders with a tie attached at the waist, crossing around and tying on the side. But as the woman loosened the ties to accommodate the growing baby, there was no way for the garment to lengthen to account for the increased length needed to cover the abdomen. As with previous attempts to solve the problem, the skirt front hiked up, becoming shorter in the front than around the sides and back.

Patent 960,687 of 1910

This dilemma set the stage for the birth of Page Boy Maternity Company. In the 1930s Edna Frankfurt, Ben and Jenny Frankfurt's oldest daughter, worked as a secretary for Magnolia Petroleum Company in Dallas. In 1933 she married Abe Ravkind, but she continued to work.17 In 1937, when she was pregnant with her second child, her sister Elsie noted that instead of looking well groomed and stylish as she usually did, Edna looked rumpled and frumpy. In fact, Elsie exclaimed, her sister looked like a “beach ball in an unmade bed.” This situation inspired Elsie to create a new and novel design and later an innovative business plan for both herself and Edna and eventually the younger sister, Louise Frankfurt.18

Elsie, who had earned a double degree in accounting and design from Southern Methodist University, asserted that she could solve the problem of the expanding front by combining the skills she had gained in her engineering drawing class with her dress design training.19 She pondered the problem that pregnant women had in covering the abdomen without hiking the skirt. Because Elsie concluded that pregnant women had shapes that were like babies—with no waistline—she believed that maternity garments must fit at the shoulders, have a top that covered the waistline, and then have a well-fitted skirt. Generating a design using engineering principles, she solved the dilemma by practicing on one of Edna's old prepregnancy suits. Elsie cut out a window in the front of the skirt and then worked out a system of loops and drawstrings to hold the skirt in place. With the hole cut in the front, she could fit the skirt snuggly around the hips and simultaneously maintain a level hemline by using the loops and tapes. Three days later Edna was wearing Elsie's new design, a navy, two-piece ensemble with an inverted pleat in the jacket back and front, and a white bow attached under a small collar. Elsie's design possessed all the flair of the well-fitted suits of the day. It had a slim skirt with a scooped opening in the front allowing the abdomen to expand through the window. The skirt was held up by several loops, and a fabric tape connected to each side of the waistband. ...