- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

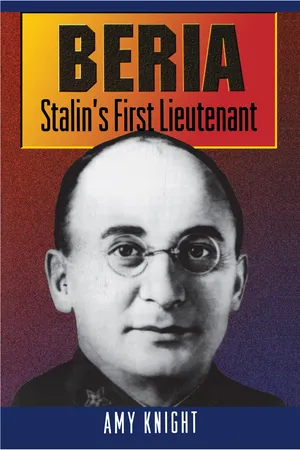

This is the first comprehensive biography of Lavrentii Beria, Stalin's notorious police chief and for many years his most powerful lieutenant. Beria has long symbolized all the evils of Stalinism, haunting the public imagination both in the West and in the former Soviet Union. Yet because his political opponents expunged his name from public memory after his dramatic arrest and execution in 1953, little has been previously published about his long and tumultuous career.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

Princeton University PressYear

2020Print ISBN

9780691010939, 9780691032573eBook ISBN

9780691214245Chapter One

EARLY LIFE AND CAREER

Ah here, o mother, is thy task. Thy sacred duty to thy land:

endow thy sons with spirits strong, with strength of heart

and honor bright. Inspire them with fraternal love,

to strive for freedom and for right.

(Ilia Chavchavadze, “To a Georgian Mother”)

GEORGIAN HERITAGE

IT IS ONE of Soviet history’s great ironies that Stalin and Beria, two of its most notorious political villains, were both born and raised in Georgia, a country renowned for the beauty and charm of its people, as well as for its rich cultural history. For centuries Georgians have enjoyed a reputation for bravery, loyalty, and high-spiritedness, and visitors to Georgia have consistently praised them for their generous hospitality, enhanced by the salubrious climate and lush Georgian countryside. The German Social Democrat Karl Kautsky, who visited Georgia in 1921, wrote: “Georgia lacks nothing to make her not only one of the most beautiful, but also one of the richest countries in the world.”1

Some historians, much to the dismay of the Georgian people, have attributed the characters of Stalin and Beria to their nationality. David Lang, for example, a noted expert on Georgia, observed: “Every medal has its reverse. In many Georgians, quick wit is matched by a quick temper, and a proneness to harbour rancour. The bravery associated with heroes like Prince Bagration, an outstanding general of the Napoleonic wars, is matched by the cruelty and vindictiveness found in such individuals as Stalin and Beria.”2 Not surprisingly, most Georgians are insulted by such slurs on their nationality, particularly since they suffered tremendously at the hands of both Beria and Stalin.3 More to the point, they would argue, is why such men came to occupy positions of power over all Soviet people, not just Georgians. Indeed, it was the Soviet system, created by the Russian-dominated Bolsheviks and run from Moscow, that fostered these men and enabled them to wield awesome destructive powers.

Although the evil acts of Beria cannot be blamed on his nationality, Georgian national culture had a profound and lasting influence on him. Georgia has a rich and ancient cultural heritage. Its civilization goes back more than three thousand years, and archaeologists have found evidence that man was living there more than fifty thousand years ago, in the early Paleolithic period.4 The Georgians cannot be classified in one of the main ethnic groups of Europe or Asia. Their languages do not belong to the Indo-European, Altaic, or Finno-Ugric linguistic groups, but rather to a southern Caucasian language group known as Kartvelian, which as far back as four thousand years ago broke up into several distinct, although related, languages. The Georgian nation itself is the product of a fusion of indigenous inhabitants with immigrants who infiltrated into Caucasia from Asia Minor in remote antiquity.5

The history of Caucasia, which in addition to Georgia, encompasses Armenia to the south and Azerbaidzhan to the southwest, reflects an amalgam of Eastern and Western influences. Toward the west Georgia extends to the Black Sea, which linked it to the cultures of Greece and Rome. To the southwest lay the Turks, who at various times were the dominant power in Caucasia. From the east, via the Caspian Sea, came incursions by the Persians. The continued struggles between Rome-Byzantium and Persia for the possession of Caucasia were drawn out because neither empire was able to defeat the other decisively. As a result, the small Caucasian states were able to retain some political and cultural autonomy despite the persistent threats of being overcome by outside powers.6

Christianity was adopted in Georgia in the fourth century during the reign of Georgian King Mirian. The conversion to Christianity provided a great stimulus to literature and the arts and helped to unify the country. It also strengthened the influence of the Roman Empire at the expense of Persia, although the latter continued to have a strong impact in Eastern Georgia. By the twelfth century a distinctive Georgian culture and civilization was formed, reflecting the influence of both Byzantium and Persia. Georgian architecture and literature flourished, and several excellent higher educational institutions were founded. Throughout the next six centuries, however, Georgia fell victim to repeated invasions which wrought havoc on its economic and political life and created internal disunity. By the mid-eighteenth century, Caucasia was “a mosaic of kingdoms, khanates and principalities, nominally under either Turkish or Iranian sovereignty but actually maintaining varying degrees of precarious autonomy or independence.”7

By this time commercial, political, and cultural ties between Georgia and Russia had begun to strengthen and in 1783, during Russia’s war with Turkey, Russia and Georgia signed the Treaty of Georgievsk, placing the eastern part of Georgia (Kartli-Kakheti) under Russian protection. Despite Russia’s commitment to defend Kartli-Kakheti, it rendered no assistance when the Turks invaded in 1785 and again in 1795. The Russians illegally annexed Kartli-Kakheti in 1801, subsequently moving westward and within the next decade extending their dominance over most of Georgia. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Georgia and the rest of Caucasia were integrated into the Russian administrative system and ambitious members of the nobility identified their interests with those of Russia. The internal conflicts and invasions from the outside for the most part ceased, but Russian domination brought little relief for the average Georgian peasant or worker, who continued to be oppressed by the feudal system imposed from above. Moreover, most Georgians remained determined to preserve their culture and traditions, resisting attempts by Moscow to Russianize them.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, at the time of Beria’s birth, opposition to the autocracy had begun to take hold in the Russian empire. Nationalist sentiments combined with radical socialist ideas to produce a liberation movement, led by the Marxist Social Democrats. In 1903 the Social Democrats split into two groups, the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks. The latter group, led by Vladimir Lenin, favored a more centralized and disciplined party organization, while the Mensheviks wanted a looser, more democratic structure for the movement. In Georgia, where Social Democrats had been active since the early 1890s, the Mensheviks predominated. When Russian Tsar Nicholas II was deposed in March 1917 the Georgians threw their support behind the new democratic provisional government in Petrograd. The bolshevik coup that overthrew the provisional government in November 1917 was opposed by Georgia and its Caucasian neighbors, which refused to recognize the new regime. On 9 April 1918, the three Caucasian republics—Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaidzhan—declared their independence from Russia and announced the creation of their own Transcaucasian Federation.

Meanwhile, as a result of the March 1918 treaty negotiated between Germany and Russia to end Russia’s long war with the Central Powers, the Russian Army abandoned Transcaucasia, leaving it vulnerable to Germany’s allies, the Turks, who moved across the border and took the Georgian city of Batumi. Because of disagreements among the three republics on how to deal with the advancing Turkish Army, the Transcaucasian Federation was soon dissolved and, on 26 May 1918, Georgia became an independent country for the first time in 116 years.8

The new parliamentary government was dominated by the Mensheviks, who had broad roots among the peasants in the countryside and also enjoyed wide support among urban workers. One of their first actions was to sign a treaty with the Turkish command at Batumi, accepting the loss of certain territories and allowing the Turks use of Georgian railways. The Menshevik Georgian government also concluded an agreement with Germany, giving it certain concessions in exchange for diplomatic recognition and protection. (The Turks continued their advance eastward, however, taking the Azerbaidzhani city of Baku in September 1918, only to retreat a month later, when the Central Powers were forced to sue for peace.)

The Georgian Mensheviks focused their efforts on enacting land reform and improving Georgia’s weak economy, while the Bolsheviks worked to undermine Georgia’s independent government by subversive means. Because they had so little popular appeal, however, they were not successful. Finally, in February 1921, having forcibly taken over both Azerbaidzhan and Armenia, bolshevik troops invaded Georgia, causing the menshevik government to fall. The invasion marked the end of Georgia’s brief phase as an independent nation. Georgia was now “Bolshevik Georgia,” where politics would henceforth be controlled by men committed to enforcing Moscow’s rule, men like Lavrentii Beria.

BERIA’S EARLY YEARS

Lavrentii Pavlovich Beria was born on 29 March 1899 in the village of Merkheuli, which is in the Sukhumi district of what later became the Abkhaz Autonomous Republic, part of the Georgian Republic.9 Georgia is divided by the Surami mountain range into western and eastern regions. The region of Abkhazia lies in the northwest corner on the Black Sea coast. Beria was a member of the Mingrelian ethnic group, a minority that lived in a low-lying densely vegetated land on the sea coast just below Abkhazia, as well as in and around the towns of Abkhazia itself. Although the Mingrelians had their own language (closely related to the Kartvelian language group, which includes Georgian), it was not written, so Georgian was used as the literary language. Their religion, which was Georgian Orthodox, also tied them to the rest of Georgia but, like other areas of Western Georgia, Mingrelia had been more heavily influenced by the Roman and Byzantine empires than Eastern Georgia.10 Mingrelians always had a strong sense of ethnic identity and their national pride made them deeply resentful of intrusions by other peoples of Georgia, including the Abkhazians.

The Mingrelians, whose population was estimated to have reached 72,103 by the time of the 1897 Russian census, were predominantly a peasant people and Beria himself came from a poor peasant family. Mingrelian society was highly patriarchal—and still is—with the extended family household at its core. Death, which served to emphasize kinship and solidarity of lineage, was mourned intensely, according to an elaborate set of rituals and rules.11 Agriculture, cattle breeding, and wine production were the principle occupations of the Mingrelians. As in other parts of Georgia and in Russia, peasants in Mingrelia had been serfs, bound to a small number of landlords, until they were emancipated in 1867. Mingrelian peasants had a tradition of rebelliousness. Ten years earlier, in 1857, three thousand of them had risen in revolt against the ruling landlord family there. Eventually Russian troops were sent in and thirty-eight peasant leaders were arrested and exiled.12 The uprising became a part of Mingrelian heritage and was looked upon with pride by later generations.

Despite the favorable climate and rich natural resources, economic productivity in Mingrelia was low, particularly during the first part of the nineteenth century. Travelers to Western Georgia noted repeatedly how poor and backward the peasants were. According to one observer:

It must be confessed that the general appearance of the Mingrelians and Gourials denotes slothfulness and slovenliness. [Given] the consequences of the exuberant fertility of the soil, and of their own low scale in the social state, which, engendering no artificial wants, they are content with merely raising so much grain as may suffice for their own consumption.13

Karl Kautsky was struck by the primitive methods of Georgian agriculture during his 1921 visit from Germany, noting that rotation of crops was quite unknown there and that the implements used recalled Biblical times. Although some outsiders attributed the poverty to racial and climatic factors, Kautsky contended that feudal dependence and the prevalence of short leases impeded the development of agriculture there.14 Whatever the causes, Mingrelia was on the outer reaches of civilization, offering little to an intelligent youth with ambition.

Beria’s mother, Marta Ivanovna, was born in 1872. She was a simple, deeply religious woman who attended church regularly all her life, maintaining close ties with other members of the religious community.15 According to one S. Danilov, who knew Beria and his family in his youth, Marta Ivanovna married twice. From the first marriage, which ended with the death of her husband, she had one son; from the second, to Pavel Khukhaevich Beria, she had three more children—Lavrentii, another son, and a daughter, Anna, born a deaf-mute in 1905.16 In a brief autobiography written in 1923 for the Communist party, Beria mentions only his sister and a niece, born around 1910 and subsequently dependent on him, so perhaps if he had brothers they were no longer living by this time.17 In addition to his immediate family, Beria had a number of cousins on both his mother’s and father’s sides, most of whom lived in Abkhazia.18 Beria’s father died while Beria was still attending higher primary school (similar to a middle school) in the town of Sukhumi, not far from his native village of Merkheuli. So, like Stalin, he was the product of a matriarchical family.

According to Danilov, Beria was a mediocre student, not excelling in any subject but considered cunning and devious. After completing school in Sukhumi in 1915 Beria went to the city of Baku in Azerbaidzhan, where he enrolled in the Baku Polytechnical School for Mechanical Construction, remaining there for the next four years. Beria probably chose Baku for his studies instead of Tbilisi, which was much closer to home, because it offered the specific course he was interested in. Nonetheless, Baku was almost six hundred kilometers from home, quite a distance for a boy of only sixteen. Beria says in his autobiograph...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Map of Georgia, 1991

- Chronology of Beria’s Life

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Early Life and Career

- Chapter Two: Service in the Georgian Political Police

- Chapter Three: Leader of Georgia and Transcaucasia: 1931-1936

- Chapter Four: The Purges in Georgia

- Chapter Five: Master of the Lubianka

- Chapter Six: The War Years

- Chapter Seven: Kremlin Politics After The War

- Chapter Eight: Beria under Fire: 1950-1953

- Chapter Nine: The Downfall of Beria

- Chapter Ten: The Aftermath

- Chapter Eleven: Beria Reconsidered

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Beria by Amy Knight in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.