![]()

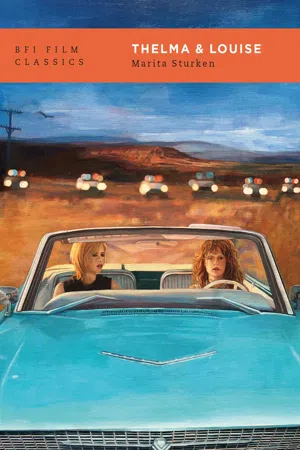

Thelma & Louise

In the summer of 1991, Thelma & Louise was talked about. It was talked about in the media, in film reviews, on television talk shows, in letters to the editor, over the dinner table, in the local bar, at the water cooler and in the bedroom. It was detested and beloved. Some critics lambasted the film as a violent, male-bashing, superficial story of implausible plot twists. At the same time, Time magazine put actresses Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis on its cover with the headline ‘Why Thelma & Louise Strikes a Nerve’, an image that was quickly converted into a T-shirt reading ‘Thelma & Louise Live Forever’.1 Many film-goers saw the film several times, waiting in anticipation for certain scenes. Academic journals soon began publishing forums on the film, with film scholars criticizing and praising the film for its genre play and gender bending. The film, which cost $17.5 million to produce, would go on to make more than $40 million.

It was, more than anything else, a film about which one was supposed to have an opinion. Was it unfair to men? Was it cathartic? Was it encouraging women to emulate bad male behaviour? A distraught reader complained to the Village Voice’s mock advice columnist Problem Lady, ‘You know you can’t go to dinner, or to a party, or even to the corner to buy carrot juice without hordes of people running up to you and saying, “So, Thelma & Louise, what about that ending, huh? Was it a feminist movie or what the hell was it? Was the violence okay or is it bad for women? What about role models?”’2

The open road

Those cultural products that generate controversy and public debate can be seen, certainly in retrospect, as profoundly, if not poignantly, indicative of particular moments of social change and political upheaval. What was it about this film that so cogently tapped into public fears and desires, that appealed to so many people as the film they had been waiting for, and that was so vehemently dismissed as misguided if not dangerous by others? Was this a crucial turning point in the representation of women, as predicted by some critics, or a regressive cheap shot of reverse sexism?

I still have my ‘Thelma & Louise Live Forever’ T-shirt, and I remember the stories told by many of my friends that summer of an exhilaration at their first experience of a ‘kick ass’ women’s movie. I remember sitting in audiences where women who I had never heard utter a word at the movies were yelling ‘yeah!’ at the screen, or hearing about friends saying to some guy hitting on them, ‘You’d better watch out, we just went to see Thelma & Louise!’ That summer, a camping trip I took with two women friends was accompanied by constant playing of the soundtrack as we drove through the deserts and mountains of California. I remember that part of the pleasure in the film was in its being a sleeper hit, an audience-driven success, and an unlikely vehicle for such big issues and debates. In the year that Thelma & Louise was released, there was a series of films which addressed issues of women and violence – La Femme Nikita, Sleeping With the Enemy, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, The Silence of the Lambs – all of which were, on the face of it, more appropriate texts for public debates about gender. Yet Thelma & Louise was by far the most controversial film of its time.

In the controversy that surrounded the film, two crucial issues were debated: the film’s relationship to feminism and its depiction of violence. What, these debates asked, was the moral message of the film? Thelma & Louise was depicted in many critical reviews as a profoundly violent film. It was called, in a now notorious review in U.S. News & World Report, a ‘paean to transformative violence … an explicit fascist theme wedded to the bleakest form of feminism’.3 Other reviews said that it ‘justifies armed robbery, manslaughter and chronic drunken driving as exercises in consciousness raising’4 and could be ‘a recruiting film for the NRA’.5 It was accused of being ‘degrading to men, with pathetic stereotypes of testosterone-crazed behaviour’6 and ‘prejudiced and sexist at its core’.7 It was defined as an example of ‘toxic feminism’,8 ‘guerrilla feminism’9 and labelled a ‘betrayal to feminism’,10 ‘a sisterhood- bash-a-thon’.11 The film was characterized as dangerous, with the potential to incite young women to lives of crime; as New York columnist Liz Smith put it, ‘I wouldn’t send any impressionable young woman I know to see “Thelma and Louise.”’12 At the same time the film was defended quite glowingly in Time magazine and in extensive articles in the New York Times, which argued ‘Lay Off Thelma & Louise’.13

‘We think you should apologise’

It would be easy to dismiss much of the debate about feminism and Thelma & Louise as a kind of anti-feminist backlash. But it was clearly more complex, in particular because many feminists were opposed to the film. The debate was rather over whose feminism the film represented, and the relationship of women to both anger and violence. In the Los Angeles Times, film critic Sheila Benson wrote, ‘Call “Thelma & Louise” anything you want but please don’t call it feminism, as some writers are already doing. As I understand it, feminism has to do with responsibility, equality, sensitivity, understanding – not revenge, retribution, or sadistic behaviour.’14 For others, however, the film synthesized feminist principles in important ways: film critic Manohla Dargis wrote, ‘In the absence of men, on the road Thelma and Louise create a paradigm of female friendship, produced out of their wilful refusal of the male world and its laws. No matter where their trip finally ends, Thelma and Louise have reinvented sisterhood for the American screen.’15 Ironically, screenwriter Callie Khouri often responded to criticisms of the film by disavowing the feminist aspects of the film, stating, ‘This isn’t the story of two women who become feminists; it’s the story of two women who become outlaws. They aren’t the martyred wife/girlfriend. They aren’t the murder victim, the psycho killer, the prostitute: they are outlaws.’16 She added, rather disingenuously, ‘The issues surrounding the film are feminist. But the film itself is not.’17

The film was released at a time in the early 90s when the second- wave feminism of the 60s and 70s had emerged from the 80s in a fractured state. Not only had both mainstream and academic feminism been subject to criticisms within feminism, specifically by women of colour and lesbians, about all of the problems of thinking about sisterhood among women who have very different ethnic, class and sexual differences, but the rise of conservatism in the 80s, in particular with Reaganism and Thatcherism in the United States and Great Britain, had also put feminist principles under continuous fire. One year after the release of Thelma & Louise, Susan Faludi’s book Backlash would become tremendously popular in providing a narrative for the turn against feminism during the 80s and 90s. Central to many criticisms of feminism at this time was the stereotypical figure of the male-bashing feminist, who wanted to gain power by taking that of men, and whose potential for violence seemed suddenly to loom large in the public consciousness. The vengeful and spiteful woman, a common figure throughout history, has been tied consistently to women’s movements, hence it is no surprise that second-wave feminism has often been accused of fuelling female revenge fantasies. Yet the figure of the vengeful female was brought to a new register in a cultural context in which women were increasingly imagined as having access to guns and the capacity to use them.

Crucial to the debates about feminism in the 80s, as it has been throughout history, was the concern of what it means for women and men to argue that women deserve the same rights and privileges as men, while also arguing that they are different from men. In second-wave feminism in the United States, this argument hinged on what critics saw as the contradictory argument that women needed special legal protection – such as the right to choose whether or not to continue a pregnancy – while they should also have equal legal rights to men. The 80s were a time of conservative attacks on Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court ruling that made abortion legal in the US, and the final rejection of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in the Senate precisely because of conservative campaigns, most notably by Phyllis Schlafly, that convinced a broader public that the ERA would mean unisex bathrooms and the forced conscription of women in the armed services.

What does it mean to be equal yet different? What happens when women do things that are considered to be the province of men only? Much of the criticism of Thelma & Louise, especially that of certain feminists, centred on its placing two women within the historically male genre of the outlaw road movie. What is the threat of women feeling free, as one critic noted, ‘to behave like – well, men’.18 Is this feminism, what Sheila Benson calls ‘high-toned “Smokey and the Bandit” with a downbeat ending and a woman at the wheel’? Does feminism mean advocating that women have the same right as men to hit the road, take delight in blowing up trucks and break the law? Yet, for others, it was precisely the bold and un-politically correct way in which the film embraced notions of liberation that had appeal. In the 90s, the internecine wars of feminism, the public backlash against its basic principles, the disabling academic debates about ‘postfeminism’, and the quelling of feminist rhetoric made the idea of liberation seem almost quaint if not historical. As Dargis writes,

What kind of feminism are we talking about anyway? The Second Sex? bell hooks? Andrea Dworkin? Susie Bright? Granted, Thelma & Louise sells a kind of feminism brut, inarticulate and inchoate. Yet after more than 10 years of Reagan, Bush, and the murky chimera of post-feminism how many can still speak the language of liberation with any assurance?19

Hence, it could be argued that it is precisely because of its crude deployment of the codes of liberation, pure and simple, that Thelma & Louise came to stand for many as an icon of feminist film.

The year in which Thelma & Louise was released, 1991, was also the year of the Gulf War, a year when large numbers of American women went into combat. Public anxieties about the role of women in war and the change in the gender status quo of the military emerged in the media as a preoccupation with depicting these women as mothers, with regular features displaying women soldiers with their children’s pictures on their helmets. In this same time period, the spate of films dealing with women and guns demonstrated the range of cultural ambivalence about women and weapons. La Femme Nikita, directed by Luc Besson, tells the story of a young delinquent woman who is recruited and trained by French intelligence into an undercover agent and killer; Terminator 2: Judgment Day, directed by James Cameron, has a central role for Linda Hamilton as a tough, gun-wielding, yet maternal, figure who is allied with the (now retooled) good terminator to save her son and the world; The Silence of the Lambs, directed by Jonathan Demme, centres on FBI trainee Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) as a feminist heroine who tracks down and kills a serial killer and saves his young female hostage; Sleeping With the Enemy features a young woman (Julia Roberts...