This is a test

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mental Health in Counselling and Psychotherapy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book examines how counsellors and psychotherapists interact with those clients who may suffer from mental health issues. While practising counsellors and psychotherapists meet clients who have problems across the entire mental health spectrum, there are a number of particular disorders that these practitioners are particularly likely to encounter. These include anxiety, depression, stress, addiction, phobias and behavioural problems. In this book, all of these conditions are explained and the ways in which therapists can best help such clients are discussed. There are sections on client assessments as well as addiction issues and understanding mental health law.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Mental Health in Counselling and Psychotherapy by Norman Claringbull in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy Counselling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Core concepts in mental health

CORE KNOWLEDGE

- ‘Mental health’ is a generic term that usually refers to the quality of a person’s general psychological functioning.

- In the UK at any given time, about 1 in 6 people are experiencing some sort of a mental health worry.

- It can be argued that in the appropriate circumstances, directly applied ‘treatments’ (medical and psychological) can have a useful place in the talking therapies.

- The mentally troubled do not necessarily have to choose ‘pills’ or ‘talk’. ‘Pills’ and ‘talk’ can often be a very productive way forward.

- Psychopathology is the systematic study of abnormal experience, cognition and behaviour – often seen as the study of the mental disorders.

FIRST THINGS FIRST: WHAT IS A MENTAL HEALTH ISSUE?

Confused about mental health? Do not worry; you are not alone. After all, a lot of mental health’s professional practitioners are just as confused too. That is why many of them find it difficult to agree about precisely what a mental health issue is. Indeed, some theorists do not even accept that there is such a human quality as ‘mental health’. For those thinkers, the mental condition that some call ‘madness’ cannot possibly exist (Vaknin, 2009; Barker and Buchanan-Barker, 2010).

A number of counsellors and psychotherapists also do not find the very idea of mental health (especially when it has a medical flavour) to be particularly helpful. It does not seem to sit right with a lot of their core beliefs around respect for individuals. Neither does it gel with their ideas about personally directed routes to emotional fulfilment. For example, one counselling trainer wrote:

When I first heard the term ‘personality disorder’ I found it offensive: it seemed to imply that the totality of an individual was deficient in some way.

(Churchill, 2011, p155)

Despite all these doubts, many talking therapists – just like the public generally – often use the term ‘mental health’ as a convenient sort of shorthand to say something about the quality of someone’s mental functioning. Once we start talking about this functioning in terms of mental health, we inevitably go on to talk about ‘good’ mental health (sanity) and ‘bad’ mental health (insanity). ‘Health’ is, of course, a medical term; for those who have a medicalised world view, therefore, it seems obvious that mental ill health is probably caused by mental illness – it must be a disease.

Not everyone agrees. Some well-known psychiatrists such as Thomas Szasz and Ronald Laing have argued that the whole concept of ‘madness’ is only a convenient myth (see review by Double, 2006). Nobody is really crazy, they say; it is just that sane people sometimes find themselves in insane situations. In other words, so-called ‘abnormal’ behaviour might actually be a perfectly normal reaction to a very abnormal situation. So by this argument, a soldier showing signs of mental disturbance due to combat stress is not ‘mad’. He is reacting perfectly rationally to the lunacy of battle. It is, of course, also true that some apparently mentally disturbed people are not suffering from mental ill health at all. Malfunctioning thyroid glands, blood sugar level imbalances or any one of a wide range of physical medical conditions can make sane people act in some bizarre ways.

There are a number of difficulties that arise when we use the term ‘mental ill health’. For example, if we think that mental distress is caused by mental ‘illness’, then we probably assume – or at least hope – that doctors will be able to cure it. Regrettably, all too often that aspiration cannot be met. Another problem arises, as the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych) tells us, from the sad fact that there is often a huge stigma attached to those who are deemed to be mentally unwell (RCPsych, 2009a; Boardman et al., 2010). Such unfortunates are often commonly, but incorrectly, seen as being dangerous ‘crazies’, unpredictable and best avoided. This view leads to the false belief that the mentally ill all need to be locked away and quarantined.

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES: WHO HAS THEM – WHAT ARE THEY?

So, who are the psychologically troubled? Who is mentally ill and who is not? The fact of the matter is that there is still considerable debate about what ‘mental health’, ‘mental ill health’, ‘sanity’, ‘insanity’ and so on actually are. Just what do these terms really mean? Are the supposedly mentally ill truly so frighteningly different from the rest of us?

The simple fact is that contrary to popular myth, the overwhelming majority of people with mental health issues are not out-of-control ‘freaks’ (Freidman, 2006). Actually, they are mostly just like you and me. In fact, they are just you and me: ordinary, everyday people who sometimes find that their lives are getting a bit too much for them. All of us – you, me, the man next door, the woman up the road – occasionally get a bit depressed, a bit anxious, a bit stressed. Sometimes these unpleasant feelings distort our lives and sometimes they do not.

However, most of us, most of the time, seem to be able get past these difficulties in one way or another. We somehow struggle across the bad bits and get through to the good bits. Unfortunately, some of us might occasionally need a bit of extra help to get there – to get by. The fact is that in the UK, at any given time, something like 1 in 6 of all adults are experiencing some sort of a mental health worry (McManus et al., 2007). This is where counsellors and psychotherapists enter the picture. They provide some of the ways in which people troubled by mental (psychological) health difficulties can be helped.

A WORKING DEFINITION OF MENTAL HEALTH

As interesting as these sorts of debates might be, we really do need to put all the academic discussions aside – at least for now – because, as real-world practitioners, we have to have a workaday definition of mental health. The problem is that finding one that we can all generally agree on, is far from easy.

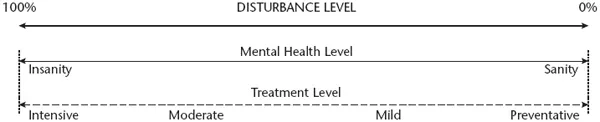

As you might be starting to see, just what we mean by the term ‘mental health issue’ seems to vary according to circumstances. Indeed, some of the more all-encompassing definitions seem to suggest that we are all mentally incapacitated, or potentially so, in some way or another all of the time (see review by Pilgrim, 2009). Just to begin with, we will use the term ‘mental disturbance’ to describe psychological and emotional distress. One way of looking at mental disturbance (mental health level) is to think of it as lying along an intensity continuum. Just where any particular individual is on that continuum will vary from time to time during that person’s life. The levels of help or treatment that such a person may or may not need will vary too, as can be seen in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Mental health continuum

A PLACE FOR THE TALKING THERAPIES?

So, what does all this mean to those of us who regularly practise in the talking therapies? What is our place in all this? How might it affect our therapeutic practices? First of all, the notion that our clients might need treatment brings any medical responses to their psychological needs firmly into the counselling and psychotherapeutic equation. Whether or not therapists ought to include such a directive approach in their professional toolboxes is likely to remain an ongoing debate. Ultimately, of course, it is a matter of professional choice and you must make up your own mind.

Some counsellors and psychotherapists might take the purist view that the psychotherapeutic explorations of our emotional or psychological concerns have nothing to do with medical models of humanity. They might argue that all mental events and experiences (good and bad) are merely part of the everyday human condition. Yet others might take the view that there is some sort of a level of mental disturbance (or distress) present in any of our clients (Claringbull, 2010). Whether this disturbance requires treatment (medical or non-medical) is a matter for even more debate. Indeed, some practitioners might argue that counselling and psychotherapy are not treatments as such but simply mutually beneficial emotional and/or psychological collaborations between therapists and their clients. Again, you must make up your own mind.

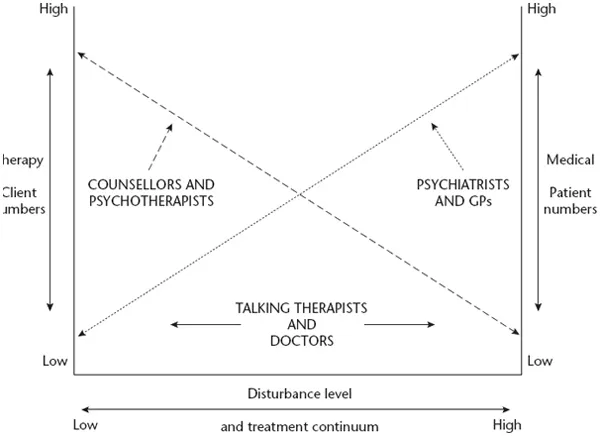

One way of exploring the ‘medical/non-medical’ (drugs/psychotherapy) question is to suggest that all of our clients/patients are experiencing some form of psychological discomfort. After all, that is why they come to see us in the first place. Whether this discomfort is an ‘illness’ or just part of being human, might be further investigated by considering just how much our clients’ supposed mental conditions affect – or even disrupt – their own lives or the lives of the people around them. It might be convenient (in this chapter anyway) to continue to view the available professional responses to emotional or mental disturbance as usually lying along a sort of psychotherapeutic/psychiatric continuum. This might suggest that as mental disturbances vary in their intensity so too should their treatment styles. See Figure 1.2.

Obviously, for some counsellors and psychotherapists the idea of ‘mental illness’ and its treatment is not a very useful concept. Their own views of the positive and negative aspects of human emotional and psychological make-up are very different. Medical science simply does not come into it. However, in this book we are going to explore the therapist’s tasks mainly from, or at least including, the medicalised aspect of mental health. Whether or not such a therapeutic attitude is likely to prove helpful for any particular client, or indeed for any particular practitioner, is of course a matter of individual judgement. As always, you must make up your own mind.

Figure 1.2: Disturbance level and medical/non-medical treatment continuum

HOW MIGHT THIS WORK IN PRACTICE?

Any experienced counsellor or psychotherapist knows that a client’s presenting problem is often only an opening gambit. The real sources of a client’s troubles, the so-called ‘real problem’, might not appear until later in the therapeutic process. The following two case studies show how two apparently very similar presenting problems were actually not very similar at all. In both cases the therapist had to make an assessment of each client’s needs based on that individual’s personal circumstances. That is why these two apparently very comparable cases were actually dealt with in two very different ways.

Case study 1.1 Working with a depressed client – a counselling answer

Jean seemed to be very low – very fed up with her life. She had lost her appetite, slept at odd hours of the day, got very snappy with her family, and generally moped around. She felt sad and empty, and she just couldn’t be bothered to keep up with her friends any more. Everything that had previously interested her now seemed to be just a waste of time. Life had become pointless. This was why she had come along to see Grace, who worked for a local counselling service.

To begin with, Grace wondered if Jean was just depressed. On the surface at least, this looked to be a likely diagnosis. Perhaps Jean’s doctor should be consulted? On the other hand, Grace was aware that there are number of psychotherapeutic approaches that are useful when working with depression. For example, should Grace suggest to Jean that they might see if some form of behaviour therapy might be helpful? What was the best thing to do?

Very sensibly, Grace decided to put off coming to any conclusions until she got to know Jean a bit better. As the introductory session progressed, Jean gradually began to talk about just how much she missed her mother. After some gentle probing Grace learned that Jean’s mum had passed away a few months back. Jean eventually admitted that she still thought about her mum all the time. Her mum was gone and not gone all at the same time. Jean still felt totally shocked whenever she remembered that her mum was dead. Somehow Jean just couldn’t get her mind around that dreadful reality.

It now seemed to Grace that Jean was not so much depressed as grieving – which has similar symptoms but a different cause. It turned out that what Jean really needed was support and a friendly ear. She needed to let out her feelings about ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- About the author

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Core concepts in mental health

- Chapter 2 Normalising the abnormal

- Chapter 3 Client assessment

- Chapter 4 Understanding depression

- Chapter 5 Understanding anxiety

- Chapter 6 Understanding schizophrenia

- Chapter 7 Understanding bipolar disorder and the personality disorders

- Chapter 8 Prescription drugs, recreational drugs and addiction

- Chapter 9 Legal and ethical issues

- Chapter 10 New ideas about mental health

- References

- Index