![]()

PART I

BACKGROUND UNDERSTANDING

![]()

1

BECOMING FAMILIAR WITH SOCIAL NETWORKS

Each one of us has our own social networks, and it is easiest to start understanding social networks through thinking about our own. So what social networks do you have? These might include friendship networks, your network of colleagues at work, and the network of individuals you know from participating in various clubs and organizations. It is quite normal to be a member of many different social networks, and in fact, social network analysis encourages you to think along these lines by separating your various social networks according to different relations. Thus, a friendship network would be one relation, an advice network a different one, and a dislike network still another relation.

Breaking down social networks according to relations is aided by how a researcher phrases questions to a respondent. For example, if I start to ask you a series of specific questions regarding the different kinds of social networks you have, it becomes easier for you, the respondent, to conceptualize all the different social networks to which you belong.

Look at the questions below and make an attempt to answer these questions for yourself. In most cases, these questions will generate new lists of names, and in some instances, you will find the same individuals popping up as answers time and time again:

- who is in your immediate family?

- who do you tend to socialize with on weekends?

- whom do you turn to for advice in making important decisions about your professional career?

- whom do you turn to for emotional support when you experience personal problems?

- whom would you ask to take care of your home if you were out of town, for example watering the plants and picking up the mail?

Take a moment and answer each of the above questions, writing down the names of people who come to mind for each question. You will probably notice two things: that each question generates a slightly different list, and that certain names appear repeatedly in different lists. Each list represents a different social network for you and there is most likely overlaps in these networks. We can label these lists to give a name to the relation that the social network represents. Thus, you can have a ‘family’ network, a ‘socializing’ network, a ‘career advice’ network, an ‘emotional support’ network and ‘home-care’ network. In addition, you can add some more information about yourself and about each person in the lists, for example, their age and gender. Below is a fictitious example for the list entitled ‘family’:

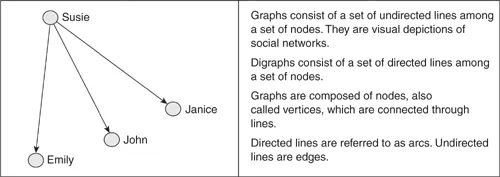

In Table 1.1, I have simply listed the people in Susie’s immediate family. The list is Susie’s social network for the relation of ‘family’. All the people listed in this social network are the actors in the network. As you will see, actors are also referred to in social network analysis as nodes and as vertices. In social network analysis, there are often multiple terms for the same concept, as this field has developed in many different disciplines. For example, an ‘actor’ is a more sociological term, whereas nodes and vertices are terms derived from graph theory. The network represented by the list in Table 1.1 is a specific kind of network in SNA, which is called an ‘ego network’. Ego networks are comprised of a focal actor (called ego) and the people to whom ego is directly connected. These people to whom ego is connected are referred to as ‘alters’. In this case, Susie is the ego and the alters are Janice, Emily and John. Susie holds a tie with each family member, and each family member’s gender and age has also been listed. Gender and age are considered additional information on each particular actor, and we refer to these additional pieces of actor information as actor attributes. Actor attributes are the same sort of attributes you come across in more traditional social science research. They include categories such as age, gender, socioeconomic class, and so forth.

Table 1.1 Susie’s immediate family

| Name | Gender | Age |

| Susie | Female | 25 |

| Janice | Female | 21 |

| Emily | Female | 47 |

| John | Male | 48 |

Through this simple example, you have already learned a fair amount about social network analysis. In particular, you have learnt some of the fundamental terminology on which social network analysis is based, namely actors, nodes, vertices, ego and ego network, alters, ties, relations and actor attributes. A social network consists of all these pieces of information, and more formally, a social network can be defined as a set of relations that apply to a set of actors, as well as any additional information on those actors and relations.

Our example above, as simple as it is, can still provide us with a means for introducing some more SNA terms. Susie’s ego network of her family represents a state relation. State relations have a degree of permanency or durability that make it relatively easy for a researcher to detect. Examples of state relations include kinship, affective relations such as trust or friendship, and affiliations such as belonging to the same club or church. State relations stand in contrast to event relations, which are more temporary sorts of relations that may or may not imply a more durable relation. Examples of event relations include attending the same meeting or conference; having a cup of coffee together; sending an email; giving advice; talking with someone; and fighting with someone. Event relations may or may not indicate a more permanent state. Usually, however, we think of event relations as individual occurrences.

Actors, vertices and nodes = the social entities linked together according to some relation

ego = the focal actor of interest

alters = the actors to whom an ego is tied

tie = what connects A to B, e.g. A is friends with B = A is tied to B.

relation = a specified set of ties among a set of actors. For example, friendship, family, etc. actor attributes = additional information on each particular actor, for example, age, gender, etc.

ego network = social network of a particular focal actor, ego, ego’s alters and the ties linking ego to alters and alters to alters

social network = a set of relations that apply to a set of social entities, and any additional information on those actors and relations

Figure 1.1 | | SNA terminology |

DESCRIBING SOCIAL NETWORKS THROUGH GRAPHS AND GRAPH THEORY

Let’s move on from this starting point. We can make a visual representation of Susie’s network by drawing a graph. A graph or digraph is a visual representation of a social network, where actors are represented as nodes or vertices and the ties are represented as lines, also called edges or arcs.

When we represent social networks as graphs and describe social networks in terms of graphs, we use terms and concepts derived from graph theory, a branch of mathematics that focuses on the quantification of networks. Although social network analysis is not the same as graph theory, many of the fundamental concepts and terms are borrowed from this field, and so it is worthwhile to spend a bit of time familiarizing oneself with some of graph theory’s basics.

In graph theory, ones says that there are n number of nodes and L number of lines. Thus, in the above graph, n = 4 and L = 3. In addition, we discuss how nodes are adjacent with each other. A node is adjacent to another node if the two share a tie between them. Thus, Susie is adjacent to each member of her family. She shares a tie with each member of her family.

To help you become better acquainted with some of the graph theory basics, I shall expand on our first example of a social network. A family network, as stated above, is one of many social networks of which an actor can be a member. Another network could be a friendship network. Friendship networks tend to span across different contexts: we have friends at our places of work, from our school, from our neighbourhood, and so forth. Sometimes these friends overlap, for example, a friend from our workplace might also live in our neighbourhood. For purposes of this present example, I would like to focus your attention on a very clearly bounded sort of friendship network, that is, the friends you have at work. For example, suppose I were to ask you the following question: ‘Whom in your workplace would you consider to be your friend?’ Most likely, your answer would not include every person with whom you work, but rather those people you feel closer to or more intimate with than the others. This would be considered your friendship network at work. Notice that this is quite different than if I were to ask you, ‘Whom do you consider to be your friend?’ without specifying whether or not I was interested in your workplace or not. In specifying the workplace, I have thus created a boundary around this particular network, i.e. I have defined what sorts of actors can be considered to be inside the network and which ones are outside my realm of interest. By specifying the boundary, I have, in essence, specified my population of interest for this particular network study. Network boundaries are an important issue which will be taken up later in this book. For now, it is good enough for you to understand that the boundary of this particular network is a particular, specified workplace.

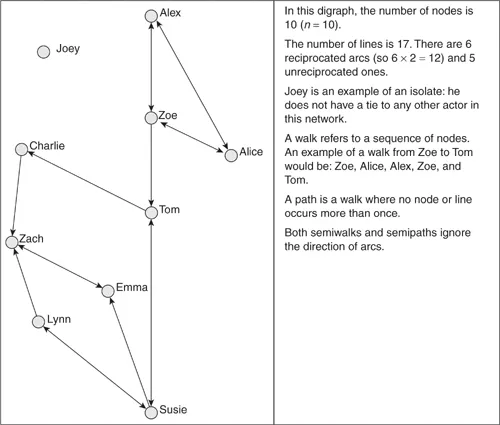

Now suppose I were to ask the exact same question to each of your colleagues. That is, each person in your workplace were asked to nominate colleagues with whom they felt they shared a friendship tie. In asking every person at your work place the same question, I have moved from studying one particular person’s ego network to studying a complete network. A complete network is one where an entire set of actors and the ties linking these actors together are studied. Once again, I can display a complete network as a graph, as shown in Figure 1.3.

Now I can introduce additional terms from graph theory to further describe this particular social network. You will notice that the above graph contains lines with arrowheads. The lines represent ties, and the arrowheads indicate the direction of the ties. In SNA terms, we would say this graph shows a directed relation, and in graph theory, a graph with directed lines is referred to as a digraph. The directed lines making up the digraph are referred to as arcs. Arcs have senders and receivers, where senders are the ones who nominate, and receivers are the nominees. In the present example, the senders are the respondents who answered the question ‘Whom in this workplace would you consider to be your friend?’, and the receivers are those actors who were nominated by the respondents as friends.

Figure 1.3 | | A digraph showing ‘Who is friends with whom at work’ |

If we did not want to pay attention to the direction of the lines, we could simply remove the arrowheads. In graph theory, a network that contains undirected lines is referred simply to as a graph, and the undirected lines are referred to as edges. Graphs, i.e. those which contains only edges, are considered the simplest to study, and thus you might choose to ignore the direction of the lines for this very reason. However, a graph might result from the nature of the relation being studied; for example, if the relation being studied is marriage, the marriage tie can be assumed to flow in both directions, so there is no need to represent that relation as a digraph.

You will also notice the Joey does not have any ties to other nodes in this graph. In this instance, Joey is an isolate, i.e. a node that does not have ties to any other actors in a network.

Displaying a social network as a graph or digraph invites a researcher to start describing certain aspects of the network. For example, we can discuss how close or far apart two nodes are from one another through the number of arcs or edges linking the two together. Considerations of distance between nodes involve the concepts of semiwalks, walks, semipaths and paths. I shall describe each of these briefly below:

In Figure 1.3, one can take a walk from Zoe to Tom by passing through Alex, Alice and Zoe. Notice that we are paying attention to the direction of the arcs in taking this walk, and that we passed by Zoe twice. Thus, a walk is a sequence of nodes, where all nodes are adjacent to one another, where each node follows the previous node, and where nodes and lines can occur more than once. The beginning node and the ending node in a walk can be different. Thus, the length of the walk is the number of lines that occur in a walk, and the lines that occur more than once in the walk are counted each time they occur. The walk from Zoe to Tom, as described above, is length 4. A much shorter walk from Zoe to Tom would be length 1.

A semiwalk simply ignores the direction of arcs. Thus, a semiwalk from Tom to Zoe is possible, even though the direction of the arc would suggest otherwise.

The notion of paths and semipaths builds on these ideas. A path is a walk in which no node and no line occurs more than once on the walk. Thus Zoe, Tom, Charlie and Zack would be an example of a path. Again, a semipath is a path that ignores the direction of arcs.

Although this seems like a lot of vocabulary, these terms and concepts are the building blocks for describing, analysing and theorizing social networks. In the remaining space of this chapter, we shall explore two other fundamentals regarding social network analysis. These are modes of networks and network matrices.

NETWORK MATRICES

The previous section focused on the display of networks as graphs and digraphs, and the terminology from graph theory used to describe these. Although visualizing networks as graphs and digraphs is useful, the reliance solely on these visual representations can become cumbersome and even chaotic as a network grows in size. For this reason (among others) ...