![]()

CHAPTER 1

WHAT TEACHERS OF LITERACY KNOW AND DO

| • attitudes • cognition • curriculum • imitation • innate • input • knowledge about language • language development • subject knowledge • processes |

This chapter aims to:

- give a sense of the importance of literacy and English

- explore the responsibilities of the teacher of literacy

- provide insight into the ways in which children develop language

- identify what you’ll need to learn

- give a sense of relief that you already know a great deal

- examine what happens in English lessons and why it happens

Teaching English is really important – that could really be the message of this whole book. Reading, writing, speaking and listening are central to the curriculum and permeate every aspect of the school day. They are wonderful accomplishments in themselves, bringing pleasure and power, but they are also essential carriers of every aspect of learning. This is a pretty strong case in itself but it is what happens in adult life to people with poor literacy that makes the work of the primary teacher so significant. The National Literacy Trust found recently that:

70% of pupils permanently excluded from school have difficulties in basic literacy skills. 25% of young offenders are said to have reading skills below those of the average seven-year-old. 60% of the prison population is said to have difficulties in basic literacy skills. (2008: 6)

Though these are horrifying statistics, it is also the everyday burden of low levels of literacy which impacts on the lives of many people. If you consider the number of times you use your reading and writing skills in a day it is easy to see what a burden it would be in our society to have problems in these key areas. Not being able to do things like using a television remote, sending a text message, finding an address would be a nuisance; being unable to read the instructions for taking a prescription or write well enough to fill in an application form could have enormous effects. Joan, a recently retired school dinner lady, described her feelings about her poor literacy levels like this:

I nearly didn’t go for the job because the thought of school still gives me the heebijeebies. All through my life I’ve been pretending – sore finger when there was writing to be done, forgot my reading glasses – I don’t even have reading glasses. Then there’s things I’d have loved to do – cooking from fancy recipes. I don’t even like being in strange places on my own in case of getting lost …

No one should go through life with this burden and, hopefully, things have moved forward so much that children who struggle with reading and writing are supported by sensitive, astute teachers.

If being literate is so important to adults then it is essential that primary teachers approach the teaching of literacy with flair, diligence and a determination that every child will be successful and will enjoy all the processes of learning. Enjoyment isn’t window dressing for learning: it is essential for progress (DfES, 2003). If this simple knowledge that literacy really matters is constantly in mind, then everything else will fall in place and classrooms will be places where children thrive as language learners. The promise all teachers make is that we will do everything possible to ensure that no one leaves primary school frightened of speaking, reading or writing or unable to draw on language skills for work and pleasure as they move towards adult life.

Expert reflection

Colette Ankers de Salis: The best teachers of literacy

Like all effective teachers, the best literacy teachers possess generic qualities that inspire and motivate children to want to learn. They have high expectations and believe in the young learners in front of them. They care. The best literacy teachers know that developing children’s literacy skills is of fundamental importance. They know that there is an undisputed link between levels of literacy and life chances; that being literate unlocks all other areas of the school curriculum and enables people to function in the real world after school. It is thus the foundation for all learning and future opportunities.

The best literacy teachers are committed to nurturing a love of the written and spoken word; they know that it is alarmingly easy to turn children off reading and writing through mundane worksheets and purposeless exercises. So they plan engaging lessons with clear learning intentions and communicate effectively with the children so that they understand what they are learning and why.

The best teachers of literacy are interested in and understand how children learn to read and write and plan stimulating lessons that build on prior skills and knowledge. They recognise that explicit teaching of letters and sounds is important but that children need opportunities to apply their developing skills and knowledge, capitalising on children’s interests to create such opportunities.

They are passionate about children’s love of reading and enthusiasm for writing. They recognise and value children’s early reading behaviours and emergent mark-making and seek to develop these skills further through stimulating and developmentally appropriate activities. These teachers understand that literacy skills depend on the development of language skills. They know writing effectively and reading for understanding are problematic in the absence of a wide vocabulary and an understanding of the grammar and richness of the English language. Thus they create a language-rich environment where things such as talk, discussion, songs and word-play are valued and embedded.

The best literacy teachers know much about how children learn to read and write yet recognise that they may not know everything. Thus they remain open to embracing new ideas and research findings through life-long learning.

(Colette Ankers de Salis is Senior Lecturer in Primary and Early Years Education, Liverpool John Moores University)

| - What groups of children are most likely to struggle with literacy in the primary years? How can teachers ensure that they experience success?

- Is motivation the most important factor for learning literacy?

- Is difficulty with reading or writing more of a burden now than it was 50 years ago?

- Can you identify times in the school day when you won’t be teaching literacy in some way?

|

What society has a right to expect of teachers of English

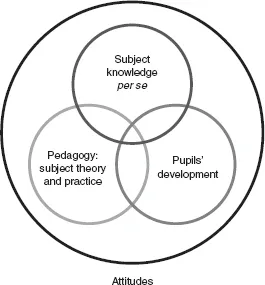

In 2007 the Teacher Development Agency considered the specific types of knowledge and understanding required by primary teachers (TDA, 2007). In their model the three main areas – subject knowledge per se, knowledge of teaching approaches and knowledge of children’s development – interlink so that when teachers are informed by all three, they work with confidence and competence. This is a good example of all the types of knowledge coming together as a student teacher makes decisions:

Figure 1.1 TDA model of subject knowledge needed by teachers. © Crown Copyright 2007. Reproduced with permission.

My teacher wanted me to teach the children how to edit using a word processor. I was pleased because it is important for people to be able to use computers. This is how I researched and planned. First I read about children editing writing on the Strategy site and I talked to my English tutor. We decided that children were going to need to know how to delete, move sentences, change words and add words. Then I made sure I could do all this using the interactive whiteboard and the school laptops. Then I checked with my teacher what children had done with changing text and it was just changing fonts. Then I thought about whether the children would be ready to look so critically at their own work because that seemed very hard and I decided that it was better for them to edit something I wrote for them. My teacher thought it would be nice to do some shared editing before getting the children to do it on their own. (Kate, student teacher)

In the TDA model, the three intersecting circles of knowledge are shown inside a circle representing the teacher’s attitudes to the subject and to the children as learners. The attitude of literacy teachers will influence every aspect of work. It is essential that teachers believe that all children can make progress in English and literacy, have a right to enjoy their learning and to have their needs met. We must also recognise that success in literacy will impact greatly on prosperity, achievement and probably happiness throughout life. Being a literacy teacher is a huge responsibility – one that we all must recognise and accept.

The subject knowledge of the curriculum

Teachers must (fairly obviously) know the material they have to teach in English lessons. The heart of this knowledge is stipulated in the National Curriculum; it is essential that children cover this in order to make the progress expected. The knowledge required to teach this should not be taxing for anyone on an Initial Teacher Training course as entry qualifications are far higher than this. However, not only must teachers be able to understand the material, they must also be able to make others understand it (Kyriacou, 1998). This is often quite demanding because we can be very effective users of our language without being fully aware of our own levels of understanding or the rules which are determining our choices (Fielding-Barnsley and Purdie, 2005) – being able to do something well doesn’t necessarily mean that you can teach it effectively.

When we come to teaching something, our own language understanding can be strained because we have to explain things which have been instinctive or intuitive before. The conscious knowledge of the structures, rules and reasons of our language is now usually called ‘knowledge about language’ though some texts will refer to it as ‘metalinguistic awareness’. It is this knowledge that we have to develop very strongly as teachers of English as it enables us to understand children’s misconceptions and to help them to understand them too (Eyres, 2007). It also helps us with the ‘why questions’ about our language: being a great teacher requires confidence with the ‘whys’ of the curriculum as well as the ‘whats’ (the expected coverage) and the ‘hows’ (effective pedagogy).

Teachers also need to know how to translate their knowledge into terms which will be understandable to children. This will require careful thought about how to link the new concept to children’s existing knowledge. It is also necessary to think about the technical terminology to be introduced and how it should be defined. One of the hardest things is to find examples which make the learning absolutely clear. For example, some people may choose to use metaphors to introduce new linguistic concepts, perhaps likening a complex sentence to a chocolate éclair! Wierzbicka (1996) explored the way in which we use figurative language to introduce new concepts. It can be an excellent way of making the concept clear but also leads to the question of when technical terminology has to be introduced. So it is sensible to explain that a complex sentence is like an éclair but less valuable to name it as one. It is debatable whether there is any value in teaching a transitional terminology which then has to be unpicked and replaced with the conventional words.

The material to be covered (the immediate subject knowledge) is simple to research. However, a teacher’s knowledge of the curriculum has to be sufficiently secure to do other things (Ofsted, 2008). When asked an unexpected question or confronted with an unusual error, teachers must have the knowledge to respond immediately with accurate knowledge or have the confidence to say, ‘I don’t know but I’ll find out for you’. Recently, one of our students was asked whether haikus ever used similes when written in Japanese. By admitting that she didn’t know and later explaining how she’d found the answer, she did a great deal to enhance the child’s knowledge of the subject, of research skills and of the value of independent thinking in the study of English.

| Before a placement, your teacher will always let you know the English topics... |