This is a test

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Research Skills for Social Work

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Social Work students often find research an intimidating and complex area of study, with many struggling to understand the core concepts and their application to practice. This book presents these concepts in an accessible and user-friendly way. Key skills and methods such as literature reviews, interviews, and questionnaires are explored in detail while the underlying ethical reasons for doing good research underpin the text. For this second edition, new material on ethnography is added.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Research Skills for Social Work by Andrew Whittaker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Planning your research

ACHIEVING A SOCIAL WORK DEGREE

This chapter will help you to develop the following capabilities from the Professional Capabilities Framework:

- Professionalism

Identify and behave as a professional social worker committed to professional development. - Values and ethics

Apply social work ethical principles and values to guide professional practice. - Knowledge

Apply knowledge of social sciences, law and social work practice theory. - Judgement

Use judgement and authority to intervene with individuals, families and communities to promote independence, provide support and prevent harm, neglect and abuse. - Critical reflection and analysis

Apply critical reflection and analysis to inform and provide a rationale for professional decision-making.

It will also introduce you to the following standards as set out in the 2008 social work subject benchmark statement:

4.2 The critical application of research knowledge from the social and human sciences, and from social work (and closely related domains) to inform understanding and to underpin action, reflection and evaluation.

4.7 Acquire and apply the habits of critical reflection, self-evaluation and consultation, and make appropriate use of research in decision-making about practice and in the evaluation of outcomes.

5.1.4 Social work theory

5.8 Skills in personal and professional development

5.9 ICT and numerical skills

7.3 An ability to use research and enquiry techniques with reflective awareness, to collect, analyse and interpret relevant information

Introduction

You are about to embark upon a process that is likely to change the way you think. You will gain tools for challenging your own thinking and the thinking of others and get a glimpse ‘behind the scenes’ at how knowledge is created. As a result, you are likely to experience more freedom than with any other part of the course to intensively study something that is interesting to you.

Historically, social work has seen itself as a ‘practical’ subject and has drawn upon other disciplines to provide a research base to inform its interventions. Sociology and psychology have been the disciplines that have been the most influential, both of which have relatively well established research bases. As social work has become a graduate profession, there has been a shift towards the discipline developing its own research base.

Developing research skills is an important part of qualifying social work programmes, which usually occurs in the final phase of the course. By this stage in your studies, you will have become accustomed to both traditional academic writing and competence-based assessments such as placement portfolios. However, the prospect of learning a new vocabulary and set of skills can be a little daunting. For example, although all students must demonstrate numerical proficiency before being accepted on the course, this may not translate into confidence in critically appraising statistical information. Even the language of research design, methodology and data analysis can seem technical and remote from students’ experiences.

ACTIVITY 1.1

Take a sheet of blank paper. Think of the term ‘research’ and jot down what ideas occur to you.

Take a separate sheet of paper and jot down the emotions provoked by the idea of engaging in research.

Take a separate sheet of paper and jot down the emotions provoked by the idea of engaging in research.

COMMENT

For many people, ‘research’ is something that is either intimidating or boring or perhaps both. It is done by other people, such as psychologists or doctors, using highly complex and technical procedures, rather than social workers. I hope to challenge these myths throughout this book and demonstrate to you that research is something that can be interesting and straightforward.

The aim of this chapter is to provide an accessible and straightforward guide through the challenges you may experience. It has begun by asking you to reflect upon your initial thoughts about engaging in research. In the next part, you will be introduced to key terms and guidance will be offered on planning your project. The stages of the process will be outlined and you will be asked to reflect upon the process of choosing a suitable topic and developing a research question. The distinction between quantitative and qualitative approaches will be discussed and illustrated using case studies of student continued projects that will be developed further in later chapters. You will be asked to consider a range of research designs from particular traditions to illustrate the wide diversity of approaches.

Key terms in research

As with any new area of study, you need to understand new terminology that can seem technical and confusing. Here are a few key terms that you will come across when studying for your research project. There is considerable debate about the exact use of specific terms, but the definitions below are generally agreed upon and are the meanings used in this book.

Data refers to the information that you are going to collect in order to answer your research question, for example the words used by your interview participants or numerical information from your questionnaires. Strictly speaking, data is a plural rather than a singular noun (the singular is ‘datum’) and this convention shall be kept throughout.

Methodology refers to the totality of how you are going to undertake your research. It includes the research approach that you will use, including your epistemological position and the specific research methods you will choose, e.g. interviews, questionnaires.

Research approach refers to the traditional division between quantitative and qualitative traditions in research, which will be discussed fully in this chapter.

Research method refers to the practical ways that you are going to use to collect your data. The four most commonly used methods in student research are interviews, questionnaires, focus groups and documentary analysis. Each method has a separate chapter.

Sampling refers to the process of selecting the participants (or other data sources, e.g. documents) that will be involved in your study. Your sample (the selection of people or other data sources) is chosen from the total possible data sources, known as the population.

Research participants replaces the outmoded term ‘research subjects’, because the latter term suggests that people involved in research should have a passive role in a process to which they are ‘subjected’. The term ‘participants’ suggests a more active and equal role, in which participation is informed and freely chosen.

Epistemology is the study of knowledge and addresses the question of what counts as legitimate knowledge. Research projects contain assumptions about what is legitimate knowledge, which is known as its epistemological position or stance. This is discussed further in this chapter.

A full glossary is provided at the end of the book.

Planning your research

Planning your research properly takes time but it is worthwhile getting it right at the beginning. It is tempting to rush into arranging interviews or focus groups or sending off your questionnaire. Although you may manage in the short term and feel you are ‘getting it done’, you run the risk of time-consuming problems later because your data do not answer your research question or are difficult to analyse.

It is important to allow yourself sufficient time to undertake your research and allow for possible delays. For example, common delays occur when trying to obtain ethical approvals, or participants cancel and you have to rearrange appointments. Similarly, transcribing interviews or focus groups takes longer than most people anticipate and data analysis even more so.

It is worthwhile keeping a research journal or log in which you can jot down ideas, notes of material that you have read, conversations that you have had and to do lists. You can record all of your thoughts as your project develops and include the texts that you identify and the results of your literature searches. It is an invaluable aid to promoting reflexivity, as it enables you to capture and examine your thoughts on the research process, the decisions that you have made and your role as researcher.

A research journal can be invaluable in the early stages to help you clarify your thinking and work through confusions and dilemmas. As you write up your research, it enables you to retrace your steps and remind yourself of earlier stages. Throughout the process, it is very helpful to have all of your material in one place rather than having to sort through separate notebooks or diaries to find a reference or an idea that you jotted down. A popular format is an electronic word-processing document with dated entries that enable you to track the progress of your research and to search for specific words. If you prefer to work on physical copies, consider having a folder containing A4 sheets that can be taken out and placed into a ring binder as you go along. Whichever format you choose, ensure that you maintain regular electronic or photocopied back-ups to make sure that the material is not lost.

The six stages of research

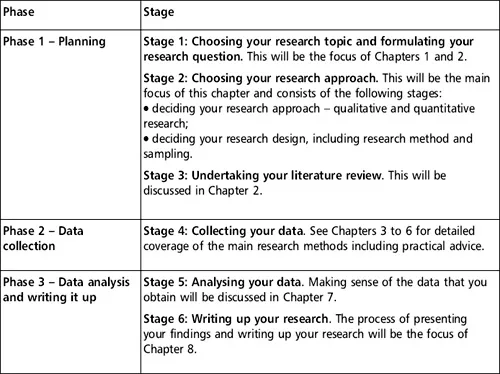

Your research project will proceed through six stages, as outlined in Figure 1.1.

Choosing your research topic and formulating your research question

The initial stage of the research process is choosing a research topic and developing it into a specific research question. Do not be tempted to formulate complicated questions on the basis that they sound academic. If you read classic research studies, you will find that they have worked well because they have chosen simple, focused research questions.

Figure 1.1 The six stages of research

Your first task is to identify a research topic and formulate your research questions. While the former is often quite easy, the latter can be quite challenging. This is because most students have one or more general areas of interest but translating this into specific research questions usually involves reformulation. We will be discussing this in more depth in Chapter 2, but a brief overview will be provided here.

When choosing your research topic, there are three main considerations:

- What are you interested in studying? You may choose a subject to research for a range of reasons, such as personal or professional experience, an interest in the academic subject or an awareness of a gap in the literature. Choose a subject that you are genuinely interested in finding something out about; otherwise it is difficult to maintain enthusiasm over an extended period. Remember that this is likely to be the part of your course where you have the greatest freedom to choose what you study.

- What will fit your course requirements? You need to familiarise yourself with the expectations of your institution about the format and scope of your research. Do not underestimate the importance of this, since your overall aim is to complete your qualification and this will only happen if your research meets the course requirements, however good it may be.

- What are you able to study? There are several components to address what it is possible to study. Firstly, what can you ethically research? You need to consider how your research might impact on your participants and other stakeholders. Secondly, what do you have the time and resources to study? An old adage for a research project is: ‘Think about what you want to do. Halve it, then halve it again and you may still struggle to get it all done.’ Thirdly, what can you get access to study? Many research projects will require you to gain access to participants and you need to consider how practical this is.

It is important that your research question is not so broad that it is unrealistic for you to be able to answer it nor so narrow that it lacks sufficient substance. It is more common for students to have difficulties because their research questions are too broad rather than too narrow.

A traditional recommendation from research supervisors is to be wary of choosing research topics that have attracted considerable recent media attention. The rationale for this is that you are likely to find a considerable amount of media coverage but little research or academic writing. The danger is that the final dissertation will reproduce the generalisations and stereotyping presented in the media reports with little evidence from research studies or academic writing. However, some topics do have a reasonable academic literature and the student may be interested in investigating how the topic has been portrayed in the media. In this case, media coverage would be a legitimate source of data for a documentary analysis (see Chapter 6).

Why formulate an overall research question?

It is important to formulate an overall research question as your project develops because it will focus your choice of research design and your literature search. It is all too easy to find yourself going in several different directions during a literature search or to collect too much unfocused data and then become confused about what to include and what to leave out.

You may find that you have more than one overall research question. If so, they need to link well to form an overall research project. If you find that you have two entirely separate research questions, you probably have two research projects and you need to decide which one you want to undertake.

Choosing your research approach and design – quantitative and qualitative research

Once you have formulated an initial research topic, you need to consider which research approach and research methods to choose. Social research has traditionally been divided into quantitative and qualitative approaches. These approaches have different views ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Planning your research

- Chapter 2 Undertaking a literature review

- Chapter 3 Interviews

- Chapter 4 Focus groups

- Chapter 5 Questionnaires

- Chapter 6 Documentary analysis

- Chapter 7 Analysing your data

- Chapter 8 Writing up your dissertation

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 Professional Capabilities Framework

- Appendix 2 Subject Benchmark for Social Work

- Glossary

- References

- Index