Introduction

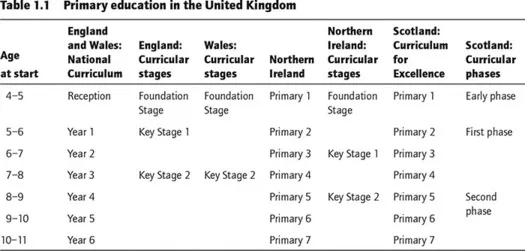

Primary education varies across the four countries of the United Kingdom – England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (see Table 1.1) – in terms of, amongst other things, curriculum and assessment. Primary classrooms are generally organised in terms of age and stage, with children taught with others of the same age who progress through the primary as a year group. The exception to this is the mixed-age or ‘composite class’ which can be found where two or more year groups may be combined within the same class; this often arises in small schools but can be a feature of any school that has an uneven cohort intake for any given year. Other factors that can determine the formation of mixed-age classes are staff complement, class size limits and available accommodation.

Primary school children across the UK are subject to constant evaluation, through formative assessment by their teachers and peers; matching pupils’ performance against curricular benchmarks through examination of class work, homework and, increasingly, through summative assessment, both internal and external, with the latter usually being at specific points in the child’s experience of schooling. In England the current assessment framework consists of a baseline assessment in Reception to assess their ability with respect to literacy reasoning and cognition on starting school; a phonics screening test at the end of Year 1 and a proposed times tables test at the end of Year 4 (starting in 2019) along with teacher assessments and Statutory Assessments or Standard Attainment Tests (SATs) at the end of:

- Key Stage 1 (Year 2) in English (reading and writing) and mathematics – these teacher marked assessments will run through till 2023; and

- Key Stage 2 (Year 6) in English (reading, and spelling, punctuation and grammar) and mathematics as well as teacher assessments in science.

In Wales, children in Years 2 to 9 classes take National Reading and Numeracy Tests; these tests, from 2018 onwards, will increasingly be administered as online tests. In Northern Ireland, children in Primary 4 to 7 classes are given a computer-based assessment in numeracy and literacy (InCAS). The Northern Irish government chose not to renew the contract for these non-compulsory assessments from 2017 onwards. In-school assessments are used to assign Levels of Progression (LoPs) at the end of Key Stage 1 (Primary 4) and at the end of Key Stage 2 (Primary 7) in the cross- curricular skills of communication, using mathematics and using ICT (information and communications technology). In Scotland, from 2017 onwards, standardised assessments will be administered to Scottish pupils in Primary 1, Primary 4 and Primary 7. These online assessments will focus on literacy and numeracy and there will be no set day or period of time when these national standardised assessments must be taken. Individual teachers and schools will decide the most appropriate time during the school year for children to take the standardised assessments.

New entrants to the teaching profession will no doubt be familiar with the basic outline given above and are choosing to come into the teaching profession for a variety of reasons such as ‘the quest for personal fulfilment; the desire to work with young people and make a difference in their lives; and the opportunity to continue a meaningful engagement with the subject of their choice. There is a strong melding here of personal aspiration; spiritual endeavour; social mission; intellectual pursuit; the desire for connectedness; and a belief in the power of ideas and relationships manifested in education to alter the conditions of their own and others’ lives for the better’ (Manuel and Hughes, 2006: 20). Research suggests that, based on their own positive and negative experiences as pupils, pre-service teachers commonly aspire to be ‘academic and pedagogically skilled and caring teacher(s)’ (Lyngsnes, 2012: 6), focusing on the relationship between teacher and learner, and taking a strong view on the teacher’s responsibility to make ‘a positive and principled contribution to society’ (Younger et al., 2004: 258). However, students are, understandably, generally unaware of the teacher’s role within the larger systems of which the individual classroom is only a part; nor are student teachers always aware of the many external constraints which there may be on their initial expectations of how they will teach. These understandings develop over the period of teacher education and beyond.

While a crucial component of teacher preparation is the time spent in schools, we believe strongly that school experience alone is not sufficient to allow you to develop a robust professional identity as a teacher which will enable you to cope with the pressures which you will face during a career in teaching in the twenty-first century. This book will support you as a student or novice primary teacher to recognise that learning and teaching are complex concepts about which many conflicting views are held. It should encourage you to gather and reflect on expert knowledge which will allow you to justify your practice not simply on the basis of experience and instinct, but on the basis of evidence from theory and research and through having considered different perspectives on key aspects of practice. At a time when teachers are under constant pressure to increase pupil attainment and to respond to different local, national and international initiatives around curriculum and practice, it is vital that we are able to articulate our knowledge and understanding of the body of knowledge which we possess about learning and teaching processes from an ‘expert’ position, as opposed to those whose understandings may be based simply on their own experiences of having been at school. And crucially, we must be sure that our practice aligns with our professional values.

Linking values and practice

Teachers across the United Kingdom are required to meet the appropriate professional standards (DfE, 2013a; GTCNI, 2011; GTCS, 2012; GTCW, 2010); each refers to values understood by the different professional bodies to be fundamental to a teacher’s professional identity. One key element of teaching standards is a commitment to social justice and inclusion and this should be seen as underpinning this book as a whole. There is a separate chapter on ‘inclusive education’ (see Chapter 8), which might suggest that we see this as a ‘stand-alone’ aspect of practice; however, this is not the case, as we operate under the assumption that we organise learning and teaching in our classrooms in ways which allow us to provide equitable opportunities for all young people to learn; that is, we understand that some will require additional support at some times for a range of different reasons but that, as far as possible, our pedagogy should allow us to include all learners without having to make significant separate provision for individuals (Florian and Black-Hawkins, 2011).

The concept of inclusive education is by no means a simple one. ‘Inclusion’, as well as being centred on issues of ‘human rights, equity, social justice and the struggle for a non-discriminatory society’ (Armstrong and Barton, 2007: 6), also has at its heart the right of individuals to be recognised and accepted for themselves. Inclusion is not something that can be ‘done to’ someone. It is not in our gift to ‘include’ anyone in our classrooms. Inclusion implies a state of ‘being’ where individuals can participate in and feel part of a larger group as themselves. While policies and overarching legislation may support and encourage the development of inclusive education, we often find conflicting policies in other areas which might lead to exclusive practices. We need then to be able to articulate clearly the reasons for our decisions around our classroom organisation and pedagogy and our response to policy directives. As we consider a few of the key issues currently impacting on primary education in the twenty-first century we will highlight questions which arise for us which underline our need to be secure in our knowledge and understanding of learning and teaching processes.

Some issues impacting on primary education

Alongside the human rights movement which has led to the development of inclusive education, and causing some tensions with issues arising from that, some of main political and economic drivers which have impacted on the education system since the late twentieth century are individualisation, globalisation, curricular change and raising attainment. It is not the aim of this chapter, or indeed this book, to discuss these in detail, but it is important that as student teachers you are aware of the challenges presented by these issues, briefly outlined below, as they will affect your life as a teacher by having an impact on the pedagogical strategies that you deploy in the classroom.

Individualisation

Since the late 1970s, there has been a move in most of the wealthy countries of the world towards much greater individualisation: that is, the extent to which individuals take responsibility for their own lives and identities. This is largely as a result of successive governments which have taken a neoliberal stance. Simply put, neoliberal philosophy is based on a belief in the market economy, holding that improvement emerges from competition; individuals are seen as entrepreneurs who manage their own lives, free from government interference as far as possible. Grasso et al. (2017) found that those coming of age during from the 1970s – often referred to as ‘Thatcher’s Children’ – through to the 1990s – the so-called ‘Blair’s Babies’ – tend to be particularly conservative in their attitudes to redistribution and welfare. Economic individualisation results in societal atomisation with individuals being generally reluctant to contribute economically to wider society beyond themselves and their family and friends.

Practical examples of this in education can be seen in ongoing changes in legislation since the 1980s which have widened parental choice when selecting a state school. Parents may choose to send children to a different school from their own local one, or to a different type of school altogether such as a ‘free’ school. This puts schools in direct competition with each other to attract ‘clients’. Education has become a business – being no longer seen as a service the state provides for its citizens at collective expense. Reay (2017: 328) argues that ‘[e]ducation is in a parlous state because on the one hand a majority of our political establishment do not want state education, they want privatised education, preferably run for profit, but on the other hand it is in a dire state because there is a lack of political will among a majority of the English public to fund a state education service if it involves them personally paying more for the service’. The other parts of the UK have not seen market forces being given such dominance as in England.

Educational legislation from the 1980s onwards helped create the conditions for the (semi-)privatisation of the state sector of schooling: for example, the hugely increased emphasis on recording and publishing statistics about pupils’ progress. It would appear that what is of ‘value’ is not learning itself but something which is measurable, particularly with respect to attainment. The increasing pressures which parents may feel to make the ‘right’ choices and to be responsible for their children getting the best possible education are significant, although there is debate about the extent to which real choice is available to those who are less able to make use of the system. For many young people the educational landscape is a bleak one in which ‘societal inequalities are played out and reproduced rather than places where they can be overcome’ (Gillies, 2008: 88). Gibbs (2016) asks, ‘[i]nstead of prioritising competition and achievement, should cooperation and understanding be at the heart of education?’ The Scottish Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) is seen as a vehicle to overcome this, with the aspiration of creating a ‘Scotland in which every child matters, where every child, regardless of his or her family background, has the best possible start in life’ (SE, 2004: 6). However, the evidence suggests that despite education leading to social mobility for many, it nevertheless, at the same time, causes social inequalities to widen such that many poor working-class families find themselves ‘stuck at the bottom of the social ladder’ (Waks, 2006: 848).

Thinking point

- What might be the impact of applying a market system, which operates on an understanding that there will be winners and losers, on the development of an inclusive education system?

- How can teachers respond effectively to parental concerns about the progress of all children in their class, using their knowledge of learning and teaching?

Globalisation

Due to the increasing speed of communications, both ‘virtually’ via the internet, and physically through significantly increased access to relatively cheap air travel, we live in a shrinking world, one in whic...